July 25, 2008

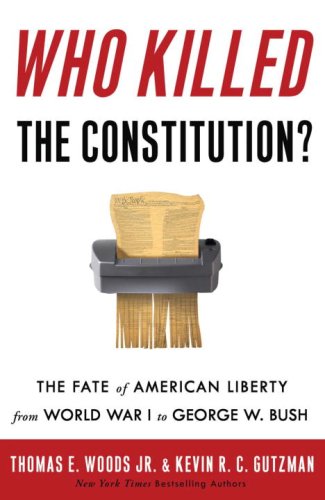

Peter Brimelow writes: "Live not by lies" was the title of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous last broadside against the Soviet Union before his expulsion in 1974. The most chilling paragraphs in this excerpt from Tom Wood and Kevin Gutzman's just-published book Who Killed the Constitution? The Fate of American Liberty From World War I to George W. Bush

Peter Brimelow writes: "Live not by lies" was the title of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's famous last broadside against the Soviet Union before his expulsion in 1974. The most chilling paragraphs in this excerpt from Tom Wood and Kevin Gutzman's just-published book Who Killed the Constitution? The Fate of American Liberty From World War I to George W. Bush describe how both opponents and supporters of the epochal 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision recognize that it cannot be justified as legal reasoning—but also how it can no longer be criticized in public. Desegregation may or may not be good public policy, but imposing it lawlessly was a critical step in the emergence of the tyrannical managerial state. One consolation: as the sudden collapse of the apparently-invincibleSoviet Union shows, mendacracy—rule by lies— is ultimately unstable.

By Thomas E. Woods, Jr. & Kevin R. C. Gutzman

The Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education was its most significant of the twentieth century. While its effects on racial assignment of students to public primary and secondary schools were limited, the prestige the Court gained through that decision set off an ongoing round of constitutional revision by federal courts that seems unlikely ever to end.

The Brown Court's lack of concern, even disdain, for the structure of the federal system and for the principle of republicanism was surprising even by the Supreme Court's standards.

The Brown Court overruled the 58-year-old decision in Plessy v. Fergusonthat racial segregation did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. It did so despite the justices' knowledge that Plessy had been correct in saying that the Fourteenth Amendment was not intended to outlaw racial segregation. Thus, Brown is properly understood not as a legal decision but as the justices' statement that since they disapproved of racial segregation, they would disallow its enforcement.

Although it was highly controversial in 1954, one rarely hears criticism of the Court's behavior in Brown today. As one prize-winning historian of Brown put it, law professors' evaluation of Brown must begin with deciding why the decision is right. Support of Brown, or at least silence on the question, is essentially required of anyone who wants to become a law professor—or, we might add, history professor or federal appointee.

This political test helps to ensure that people in those positions will not interpret the Constitution as its ratifiers understood it. As Judge Richard Posner, perhaps the leading contemporary American legal scholar, says,

"No constitutional theory that implies that Brown … was decided incorrectly will receive a fair hearing nowadays, though on a consistent application of originalism it was decided incorrectly." [Bork and Beethoven. 42 Stanford Law Review 1365 (1990)]

One's constitutional theory must support Brown; Brown is contrary to originalism; therefore, originalism will not receive a fair hearing. Another way of saying this is that Brown is more important than the Constitution.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866, which the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to constitutionalize, was amended to remove a general ban on discrimination. Twenty-four of the 37 states at the time the amendment was proposed to the states segregated their schools, which makes it hard to believe that the state legislatures would have overlooked school segregation in discussing an amendment intended to abolish that practice.

Besides, Congress segregated schools in the District of Columbia from 1864 on, and it omitted to address this issue in the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Finally, asks historian Richard Kluger, "Why, in fact, had the Fifteenth Amendment been necessary at all, if the reach of the Fourteenth was all that its most expansive interpreters had insisted? Could it be reasonably claimed that segregation had been outlawed by the Fourteenth when the yet more basic emblem of citizenship—the ballot—had been withheld from the Negro under that amendment?" [Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America's Struggle for Equality, p. 635]

Eminent historian Henry Steele Commager, advisor to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in Brown, found that Congress did not "intend that [the Fourteenth Amendment] should be used to end segregation in schools", and so the NAACP should not argue about the original understanding of the Amendment.

Similar conclusions were reached inside the Supreme Court. Justice Felix Frankfurter's clerk, Alexander Bickel, reported that "it is impossible to conclude that the 39th Congress intended that segregation be abolished; impossible also to conclude that they foresaw it might be, under the language they were adopting".

Bickel added that the language of the Fourteenth Amendment itself could be said to be too vague to answer the question at issue—whether segregation of schools was unconstitutional—one way or the other. Once the uncertainty of the Fourteenth Amendment's meaning had been established, Frankfurter might more plausibly argue that it should be read to mandate a ban on school segregation.

Frankfurter was then and is now typically characterized as a proponent of "judicial restraint," the idea that judges should allow the democratic process to determine the outcome of most policy disputes. Arguing for "judicial restraint" had served his policy preferences well in the 1930s, but the Supreme Court Revolution of 1937 had left liberals in control of the judiciary, so that Frankfurter no longer needed to wear that mask.

Chief justice Earl Warren joined Frankfurter in favoring a ban on school segregation. He lobbied his colleagues vigorously in the days before Brown in a way that recalls the behavior of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and President James Buchanan before Dred Scott v. Sandford.

The lobbying process was difficult because the Court's precedents said that school segregation was constitutional, and Frankfurter was not the only justice who knew that those precedents were consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment's intended meaning. Justice Robert Jackson circulated a memorandum in which he explained, "I simply cannot find, in surveying all the usual sources of law, anything which warrants me in saying that [the Court's decision invalidating school segregation] is required by the original purpose and intent of the Fourteenth or Fifth Amendment". The Court must concede that it was "declaring new law for a new day"– that is, amending the Constitution.

How could one account for this assumption by the Court of a power that Article V of the Constitution left to the states? As Frankfurter explained, the original understanding was not alone binding: "The effect of changes in men's feelings for what is right and just is equally relevant in determining whether a discrimination denies the equal protection of the laws".

How did Frankfurter propose to identify "changes in men's feelings for what is right and just"? Not through elections, because what he intended was for the unelected members of the Court to invalidate countless state and local laws enacted by elected state and local legislators. No, he would poll the justices, who would serve as America's supreme legislative body, a kind of super Senate.

"My instincts and feelings", Warren said, "lead me to say that, in these cases we should abolish the practice of segregation in the public schools—but in a tolerant way".

Warren's practice of putting what Justice Abe Fortas called "human values" first in judging was here on full display. Fortas observed, "Opposition based on the hemstitching and embroidery of the law appeared petty in terms of Warren's basic value approach."

The justices' oath to uphold the Constitution—among other ways, by leaving amending and legislating to federal and state legislators—was as naught before this "basic value approach". As Jackson put it, the difficulty was "to make a judicial decision out of a political conclusion".

The New York Times headline the day after Brown captured Warren's approach: "A Sociological Decision: Court Founded Its Segregation Ruling on Hearts and Minds Rather Than Laws." [By James Reston, May 18, 1954]

In other words, Brown was not a legal or constitutional decision, but an anti-legal, anti-constitutional one, a legislative act.

Warren kicked off his opinion for the Court in Brown by noting that the question was whether it was constitutional under the Equal Protection Clause to segregate students by race. Warren said that extensive consideration of the historical record did not answer the question what the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to mean in this regard.

There was no public schooling in many areas when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, Warren noted, and where there was public schooling, it in many places was rudimentary. "As a result", he says, "it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education".

Actually, the reason why the sponsors of the Fourteenth Amendment had not described its intended effect on education was that they did not intend for it to have any effect on education.

It would have been shocking if Congress, composed of members from a North thoroughly antagonistic to blacks, had passed an amendment intended in part to extend a right to unsegregated public education to blacks.

Bowing to Justice Jackson, Warren conceded that he intended to enunciate "new law for a new day": "In approaching this problem", he said, "we cannot turn the clock back to 1868 when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written".

In time, Brown would become the great moral bludgeon that beat the American idea of constitutionalism—of a written charter strictly limiting the powers of office-holders—to death.

Originalists' constitutional objections to any policy would elicit the question: "But do you oppose Brown v. Board of Education?"

Few would have the courage to say: "As a constitutional matter, yes, I do".

Thomas E. Woods, Jr. [send him mail] is senior fellow in American history at the Ludwig von Mises Institute. His New York Times bestseller The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History was reviewed here on VDARE.com on in 2005. Kevin R. C. Gutzman, J.D., Ph.D. [send him mail], Associate Professor of History at Western Connecticut State University, is the author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution

.