The transience of showbiz glory. The Easter fire at Notre Dame in Paris was distressing, of course. I was a bit less distressed than the average, for reasons I expressed in my April 19th podcast. But yes: a great shame, and a real esthetic loss.

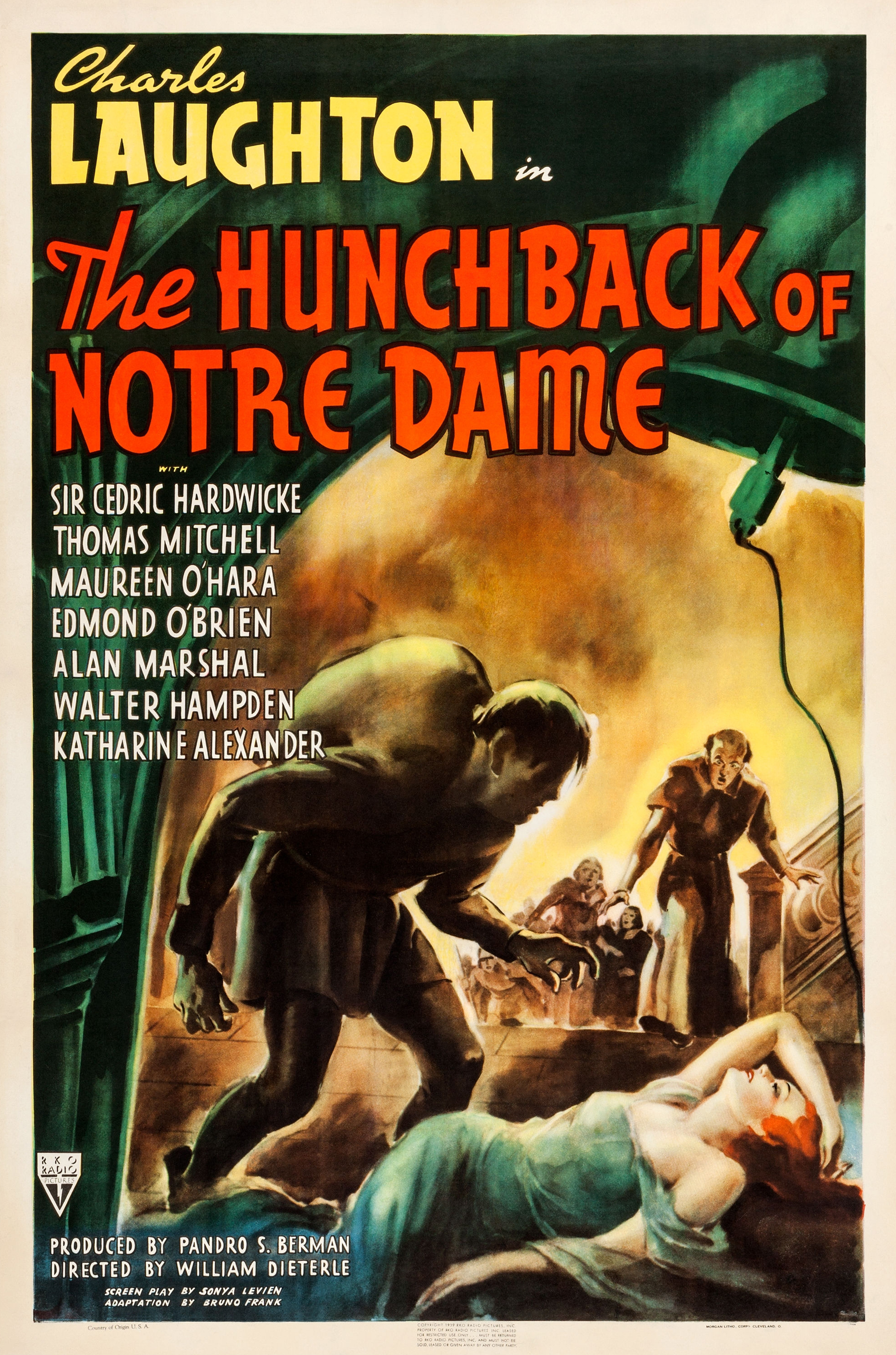

For an English child of the 1950s Notre Dame is for ever linked with the movie actor Charles Laughton, who played Quasimodo in the 1939 version of Victor Hugo's novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

It's not actually clear to me why that should be. I was born too late to see the movie when it was in theaters; there were of course no video tapes or DVDs in the 1950s; and the Derbyshires didn't acquire a TV set until I was thirteen.

It's not actually clear to me why that should be. I was born too late to see the movie when it was in theaters; there were of course no video tapes or DVDs in the 1950s; and the Derbyshires didn't acquire a TV set until I was thirteen.

We just seemed to know about Laughton's Quasimodo by osmosis. Wits of the lower kind all had Laughton impersonations in their annoying repertoires. Visiting your house, friends and relatives of that species would announce themselves by calling "Sanctuary! Sanctuary!" through the front-door mail slot; then, when you opened the door, they would lurch in hunchbackwise saying, "Sanctuary much!" Everybody got the joke. Or "joke."

I'm not sure I ever did see the Charles Laughton movie. I read the novel later on in life, and remember being surprised at the barely-concealed sado-eroticism of it. Disney made a movie version of that? Disney?

Laughton's bio at IMDb.com is a sad reminder of the transience of showbiz glory. He was a huge star in his time, by no means only in Britain. (He became a U.S. citizen, died in Hollywood, and is buried at Forest Lawn.) Now he's pretty much forgotten.

The last time I heard his name mentioned was in the silly 2001 Bruce Willis / Cate Blanchett caper flick Bandits, when Billy Bob Thornton, listing his phobias for Cate, tells her: "I'm afraid of Charles Laughton, actually." The YouTube clip of that scene mis-spells Laughton's name in the subtitles …

Easter and Passover. Several Radio Derb listeners emailed in to scold me for saying that "the Jewish calendar is lunar." Some of it is, they allowed, but some other of it isn't.

Sure, I knew that. I was speaking loosely. Do you really want to bandy calendricals with a guy who knows his date of birth in Mayan?

Any significant calendar system for common use (so not, for example, Astronomer's Julian) needs to have both solar and lunar components. Every agricultural society needs to track solar cycles to know when to plant and when to harvest; the moon seems to govern some natural processes (tides, menstruation) and is handy on dark nights when artificial light is hard to come by.

(Among those natural processes are some disturbances of the mind; hence "lunacy." That sounds like empty superstition; but a truthful, level-headed acquaintance of mine who worked as a counsellor and on-call rescuer to alcoholic members of a big metropolitan labor union told me that full moon was his busiest time.)

Still, any particular calendar leans one way or the other—more solar or more lunar. That's why the date of Easter moves around. Easter Sunday is defined by a combination of lunar and solar events (it's the first Sunday following the first full moon on or after March 21st), whereas the rest of the Christian calendar—Christmas, Saints' Days, and so on—is pretty solidly solar.

The Jewish calendar leans more lunar, that's all I was saying. Passover starts on a full moon.

And then there's the vexed question: Why isn't Easter celebrated at Passover? Jesus, like other first-century Jews who could make the trip, went to Jerusalem for Passover to purify himself at the temple. That was when he was arrested and executed. The Last Supper was a Passover Seder. So how is it that in (for example) A.D. 2024 Easter Sunday will be March 31st but Passover starts April 22nd?

And then there's the vexed question: Why isn't Easter celebrated at Passover? Jesus, like other first-century Jews who could make the trip, went to Jerusalem for Passover to purify himself at the temple. That was when he was arrested and executed. The Last Supper was a Passover Seder. So how is it that in (for example) A.D. 2024 Easter Sunday will be March 31st but Passover starts April 22nd?

Here you really do get into the calendrical weeds. The perps here are the Council of Nicea in A.D. 325. As best I can understand it, the Emperor Constantine, who called the council, wanted to separate his now-official church clearly from the Jews, to express disapproval of their having killed Jesus.

And the Easter Bunny? No idea.

Qing Ming. The traditional Chinese calendar also leans lunar. The big festivals that Round Eyes know about—New Year, Lantern, Dragon Boat, Mid-Autumn—are all lunar.

There is some solar structure in the traditional Chinese calendar too, though. Just as Easter moves around in our solar calendar because it's lunar, there is a major Chinese festival that moves around in their lunar calendar because it's solar.

This is Qing Ming, the festival of Pure Brightness. Because it's solar, it's pretty well fixed in our calendar, always occurring on April 4th or 5th. (Explaining that one day variation gets you really deep down in the weeds.)

How do you celebrate Qing Ming? The main thing is, you sweep the graves of your ancestors. The Derb ancestors, on both sides of the family, passed away on distant continents, and recent generations were anyway cremated, not interred; so neither I nor Mrs Derb could carry out the proper observances this April 5th.

My lady did the best she could for us, going up the back yard that evening and burning some Hell Money in the family barbecue pit.

For the ancestors. If you mention Qing Ming to an educated Chinese person there is an excellent chance he'll respond by rattling off the poem about it by the ninth-century poet Du Mu.

While my better half was burning Hell Money out back, I recorded a reading of that poem and put it on my website.

What with her Hell Money and my poetry reading, we figure the ancestors should rest in peace for another year.

(Du Mu is not to be confused with the much more famous eighth-century poet Du Fu, who can be heard moving around behind the scenery in Fire from the Sun.)

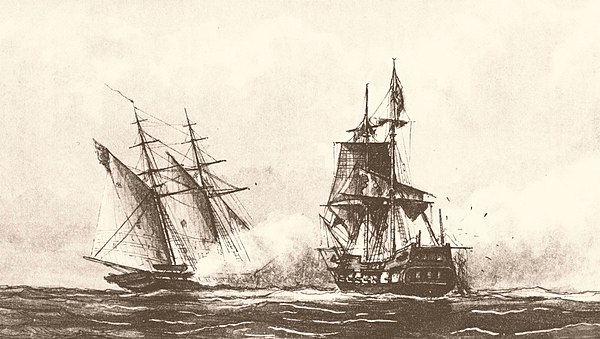

Nonfiction book of the month. On a friend's recommendation, as part of the everlasting project to fill gaps in my historical knowledge, I read Whipple's To the Shores of Tripoli, which is of course about the First Barbary War of 1801-1805.

What a mess! All I knew about this war prior to reading Whipple—I mean, all I thought I knew—was that Thomas Jefferson at last got fed up with the North African states preying on American shipping, had given them a good sharp lesson, and that was the end of that.

In fact the war was a bungled cluster-hug, the young republic's military men, president, legislators, and diplomats falling over each other's feet in a clumsy dance that is painful to read about.

In fact the war was a bungled cluster-hug, the young republic's military men, president, legislators, and diplomats falling over each other's feet in a clumsy dance that is painful to read about.

The U.S.A. was a comparatively minor power with not much money to spend on military establishments; the big European nations were distracted by the Napoleonic Wars; and communications across three thousand miles took weeks. The piracy problem wasn't decisively settled until a decade later, after Napoleon had been worn down and "the War of 1812 [had] proved the mettle of the U.S. Navy."

There's some thrilling stuff in there, though—especially the capture of Derna. I'm surprised William Eaton isn't better-known: I confess I had never heard of him.

Eaton was another twelve-pointer, like Hernán Cortés (who, by the way, also fought a couple of rounds with the pirate-rulers of the Barbary Coast, nearly getting drowned as a result). An interesting question for discussion is: Which of these two men, Eaton and Cortés, was treated worse by his own government? It looks to me like Eaton, but I'll entertain opposing opinions.

As in any war, there is tragedy and comedy to contemplate. For tragedy, spare a thought for the four crewmen of the warship Philadelphia in the passage below. The Philadelphia had been captured by the bashaw (ruler) of Tripoli and its officers and crew held as prisoners for nearly two years. Under the terms of the treaty that ended the war, they were to be repatriated.

Of the 307 officers and crew only six had died, none of them officers. When the survivors were about to be released, the bashaw sent for the five renegade sailors who had professed to turn Muslim. Yusuf offered them the opportunity to renounce their conversion and return to the squadron. Only one … elected to remain a Muslim and stay in Tripoli. The others chose to leave; one of them had a wife and four children at home. But the bashaw, evidently regarding their Muslim masquerade as an insult to his religion, promptly called the guards and had them marched away. "We had a glimpse of them as they passed our prison," marine private Ray recalled, "and could see horror and despair depicted in their countenances." They were never heard from again. Consul Lear chose not to protest.

For comedy I'll take the fate of the Barbary admiral Mahomet Rais, who lost his own ship to the American sloop Enterprise:

For comedy I'll take the fate of the Barbary admiral Mahomet Rais, who lost his own ship to the American sloop Enterprise:

Rais made it [back] to Tripoli, where he was greeted by a furious bashaw who stripped him of command and sent him riding through the streets mounted backward on a jackass with sheep's entrails hung round his neck. For good measure the humiliated ex-admiral was also given 500 bastinadoes.

You win some, you lose some.

Breaking in to privacy's last citadel. Brain-machine interfaces—BMIs—seem to be edging their way out of the labs into everyday reality. Scientific American, April 1st:

Machines That Read Your Brain Waves

Thanks to noninvasive tools that have been around for decades, such as electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), physicians and neuroscientists can measure changes in your brain without drilling a hole in your skull. And now some of the problems that made these tools finicky, expensive and hard to interpret are being ironed out, meaning that neural interfaces are suddenly showing up at Amazon and Target. Which presents a challenge because measuring brain activity isn't like making microwave popcorn. There are enormous privacy and ethical issues at stake.

Well, yes. There's nothing more private than "brain activity," a category of phenomena that includes, though it's not limited to, your thoughts.

The University of California, April 24th:

A state-of-the-art brain-machine interface created by UC San Francisco neuroscientists can generate natural-sounding synthetic speech by using brain activity to control a virtual vocal tract—an anatomically detailed computer simulation including the lips, jaw, tongue and larynx.

Don't forget those uvular consonants, guys!

The pop-science outlets are all talking about these BMI advances. Even discounting for a certain quantity of hype and some false dawns, it looks as though technology is poised to invade the last citadel of privacy and personal autonomy—what Sam Beckett called "the ring of bone," i.e. the human skull. Our thoughts may not be private much longer.

I'm ready for it. As a science-fiction addict from way back in the Golden Age of that genre—the middle decades of the 20th century—I was reading stories about telepathy—and thinking about it, as I'm sure any telepaths in my neighborhood could have told you—while still in short pants.

I'm ready for it. As a science-fiction addict from way back in the Golden Age of that genre—the middle decades of the 20th century—I was reading stories about telepathy—and thinking about it, as I'm sure any telepaths in my neighborhood could have told you—while still in short pants.

The four biggest themes in Golden Age sci-fi were: space exploration, time travel, robotics, and telepathy. Of those four, telepathy has proven least durable in popular culture. There were some major telepathy hits in Golden Age literature—A.E. Van Vogt's Slan (1940), Alfred Bester's The Demolished Man (1953), Theodore Sturgeon's More Than Human (1953), John Wyndham's The Chrysalids (1955)—but telepathy in movies and TV has been below the major-hit level, and usually gets yoked with telekinesis and teleportation for visual punch.

There's just not much visual punch in thoughts.

Three to Conquer. One of the best telepath-normie encounters from that era is in Chapter 4 of Eric Frank Russell's Three to Conquer (1955).

The novel's main character, Wade Harper, is a natural telepath. He figured out in infancy, though, that his best life option was secrecy. Nobody knows he's a telepath. He lives a normal life, only occasionally, carefully, helping out law enforcement when he can do so without revealing his talent.

The novel's main character, Wade Harper, is a natural telepath. He figured out in infancy, though, that his best life option was secrecy. Nobody knows he's a telepath. He lives a normal life, only occasionally, carefully, helping out law enforcement when he can do so without revealing his talent.

By chance he encounters Joyce Whittingham, a normal-seeming woman whose nervous system—including of course her thoughts—has been taken over by malevolent aliens. He kills her/it, and is soon the subject of a police manhunt.

Grasping that humanity is in danger, he decides to unmask himself to the authorities, to help them track down other normal-looking people who've been taken over. He makes for FBI headquarters in Washington, DC and turns himself in as the woman's killer, but has to talk his way past low-level "shields."

"The Whittingham business has to do more or less with national security. Therefore I can talk only so someone who'll know what I'm talking about."

"That would be Jameson," promptly whispered Pritchard's thoughts.

"Such as Jameson," Harper added.

They reacted as though he had uttered a holy name in the unholy precincts of a cheap saloon.

"Or whoever is his boss," said Harper for good measure.

With a touch of severity, Pritchard demanded, "You just said that Stevens is the only member of the FBI known to you. So how do you know of Jameson? Come to that, how did you know my name?"

"He knew mine too," put in Slade, openly itching for a plausible explanation.

"That's a problem I'll solve only in the presence of somebody way up top," said Harper. He smiled at Pritchard and inquired, "How's your body?"

"Eh?"

Out of the other's bafflement Harper extracted a clear and detailed picture of the body, said in helpful tones, "You have a fish-shaped birthmark on the inside of your left thigh."

Pritchard goes off to check with Jameson in a different office. In his absence, Harper asks Slade for a sheet of paper and commences writing.

He scribbled with great rapidity, finished a short time before Pritchard's return.

"He won't see you," announced Pritchard with a that-is-that air.

"I know." Harper gave him the paper.

Glancing over it, Pritchard popped his eyes, ran out full tilt. Slade stared after him, turning a questioning gaze upon Harper.

"That was a complete and accurate transcript of their conversation," Harper informed. "Want to lay any bets against him seeing me now?"

The fun thing about being a telepath would be playing head games like that with normies. The downside would of course be that once you'd unmasked yourself, nobody would want to be around you. And try getting into a poker game!

Scourby's Bible. I browsed the latest Great Courses brochure, looking for a course of lectures to listen to while I do my work-out. Nothing appealed to me sufficiently; so on an impulse I downloaded Alexander Scourby's reading of the entire King James Bible instead.

A friend advertised the Scourby readings to me a year ago and I've had them in mind ever since. I'm much more a reader than a listener, though, and I've been telling myself for years that one day—one day!—I shall set myself to read the whole KJV on a proper reading plan.

A friend advertised the Scourby readings to me a year ago and I've had them in mind ever since. I'm much more a reader than a listener, though, and I've been telling myself for years that one day—one day!—I shall set myself to read the whole KJV on a proper reading plan.

Now, a year older, I've turned some kind of corner. I've resigned myself to the fact that there are some things I shall never get around to, reading the Bible most likely one of them. So why not just listen to Scourby? I paid the twenty bucks and did the download. It's a little over a gigabyte, which is 47 hours of audio—about a minute and a half of audio per cent.

I've just finished up Genesis. Scourby's voice is exactly right for the job. He breezes through the begats, never tripping over a name. I would want a couple of practice runs at verses like Gen. 46:17:

And the sons of Asher: Imnah, and Ishvar, and Ishvi, and Beriah, and Serah, their sister; and the sons of Beriah: Heber, and Malchiel.

I don't think I could suppress an occasional snicker, either. Gen. 46:21:

And the sons of Benjamin were Bela, and Becher, and Ashbel, Gera, and Na'aman, Ehi, and Rosh, Muppim, and Huppim, and Ard.

Whatever became of Muppim, and Huppim, and Ard? Were they, perhaps at some unconscious level, the inspiration for Eugene Field's Wynken, Blynken, and Nod? (And is Eugene Field a dead ringer for Stephen Miller, or what? Hey—focus, Derb, focus!)

Scourby, however, keeps the same level, authoritative, snicker-free tone throughout. I can't wait to hear how he copes with Mahershalalhashbaz and Chushanrishathaim.

Math Corner. I'm occasionally asked whether Mrs Derbyshire shares my mathematical inclinations.

Answer: Not at all. My lady is highly intelligent, but her intelligence is concentrated over in the verbal zone. Her command of English is near-total, though she didn't start learning until her late teens. She grills me constantly about vocabulary, grammar, and usage. Just this evening:

She: "Why do we say 'spring a leak'? Why 'spring'?"

Me: "Uh … Well, see … It's like a spring of fresh water bursting out of the ground. See?"

She: "But that's a noun. 'Spring' the verb means 'jump.' And it springs a leak. Where did it jump?"

Me: "Uhhh … Oh wait, I forgot to put the garbage out."

She makes fun of my math interests, in a good-natured spousely way. Just recently, for example she tweaked me by emailing this, that was going around on one of her social-media networks.

For once I returned her serve right back over the net. Within a very few minutes I'd emailed my reply:

But that's EASY! The value of the integral is −2.981266944005515…

Not quite sure how you get a PIN out of that, though.

I used an app, of course. (This one.) That the internet has made math chores a whole lot easier, is true. That it's taken all the fun out of math, is false, at any rate if you have an un-mathematical spouse.

![2010-12-24dl[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2010-12-24dl1-150x112.jpg) John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him.) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com: FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him.) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com: FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

For years he’s been podcasting at Radio Derb, now available at VDARE.com for no charge. His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire's writings at VDARE.com can do so here.