Here on the Dissident Right, we try our best to keep our peckers up. If we were to believe that all is lost, that the game is up, that the National Question has been dispositively answered by the massed forces of Neoconnery and Cultural Marxism, there would be no point our continuing to write and speak in opposition.

And there are indeed some positive signs to cheer us, some lights flickering in the gloom. The central position we take here at VDARE.com—patriotic immigration reform—is widely popular, not just in the U.S.A. but all over the West. Surely such widespread popular feeling must find political expression sooner or later.

Important and respectable people have repudiated multiculturalism. And the horrible Obama clique may soon be gone.

True, what replaces them will not be much better, but it will be better. Dum spiro, spero—while we breathe, we hope.

Yet hoping is easier at some times than at others. I found it particularly difficult when reading about Business Insider's attack on Peter Brimelow and the similar Daily Kos attack triggered by Brimelow’s recent article on the “root causes” of the Sikh Temple Shootings.

To tell the truth, in fact, utter despair set in. I've been trying my best to talk myself out of it, with mixed success.

Imagine, if you can, a left-wing website promoting some aspects of Cultural Marxism (the normalization of homosexuality, for example) or actual Marxism (public ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange, perhaps) as vigorously as we at VDARE.com try to promote demographic stability and an end to official, legal racial favoritism. Imagine further that this left-wing website is owned by a person with a day job unrelated to the website's main topics—an architect, say.

Now imagine that opponents of the website's viewpoint are striving to discredit that owner with his employers, to get him fired. They are broadcasting the employers' names and email addresses, urging others to join them in the effort.

Can you imagine any of that? Of course you can't. It is not imaginable.

Who—who of any consequence—would think it discreditable for a person to run a website promoting Marxism, cultural or otherwise? Certainly you could never get anyone fired for such a thing; or if somehow you did, there would be an almighty uproar from the media, the academy, the Department of Justice, and all other points of the compass.

Yet here is just such an effort under way to get Peter Brimelow fired from his day job as a financial columnist. It is by no means inconceivable that the effort could succeed.

This is simply awful. Have we now reached a point where holding heterodox opinions on race or nationhood can get you fired from a job not related to those issues?

We are slipping into totalitarianism: into a state of affairs where to hold certain opinions is to be excluded from normal society, to be unemployable.

Nor will it stop there; it never does. The gatekeepers of orthodoxy—the commissars—are waxing strong, and are arrogant in their strength. You have to engage with these people to experience the full furnace blast of their arrogance.

I recently did so, with an editor at Wikipedia called "Andy The Grump." He was foul-mouthed—our cultural overlords cannot express a thought without profanity—and contemptuous, and invincibly certain that he was on the winning side, I on the other.

Perhaps he’s right. The thought came upon me, as it has done quite a lot this past few years, that I shall likely end up in a labor camp. I can't keep my mouth shut; I can't clap along with the Kumbaya; and I can't pretend assent to propositions that seem to me to be false. In the world we are fast heading into, that makes me camp fodder for sure.

Well, at least I know the territory. In my thirties, I went through a phase of reading camp literature, most of it from the U.S.S.R. Solzhenitsyn is the author everyone knows, but there were many others. I no longer have my collection of camp books, so what follows is mostly from memory.

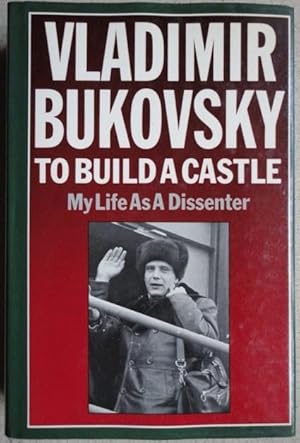

My favorite was Vladimir Bukovsky, whose autobiographical book To Build A Castle is a classic of late-Soviet camp life.

My favorite was Vladimir Bukovsky, whose autobiographical book To Build A Castle is a classic of late-Soviet camp life.

Bukovsky did his time in the 1960s and 1970s. He had no religious or ethnic ax to grind and was not an advocate of any cause or system. He was just ornery. He would not admire the Emperor's new clothes; he would not affirm that two plus two equals five; he would not chant along with the official lies.

This I admire very much. The world needs more Bukovskys. America could use a few.

The best camp writer from a literary point of view was Varlam Shalamov, who was in and out of camps all through the 1930s and 1940s. Shalamov saw the very worst of the Gulag. He spent years in the gold-mining camps of Kolyma (pronounced "kally-MAH") in far Siberia, which Solzhenitsyn called "the North Pole of cold and cruelty." In his book Kolyma Tales, Shalamov semi-fictionalized these dreadful experiences, often with surprising lyricism. He seems, for example, to have taken pleasure in the wild Siberian landscapes, at least in the short summer when they were not buried under snow.

I didn't restrict my reading just to Soviet accounts. Greta Buber's Under Two Dictators has stuck in my mind. Buber was a German communist who fled to Moscow when Hitler took power. She was arrested in Stalin's 1937 purges and spent two years in Soviet camps. Then she was returned to Germany under the terms of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and spent six years in Ravensbrück. An exceptionally tough old bird, Buber died at last in November 1989, aged 88.

At the time I was going through this phase, the Chinese camps had not produced much. The main exhibit was Jean Pasqualini's 1973 book Prisoner Of Mao. Pasqualini, born 1926 to a French father and a Chinese mother—he is sometimes referred to by his Chinese name, Bao Ruowang (鮑若望)—did seven years in Chinese camps, 1957-64, before being released via a diplomatic fluke.

Those seven years included the period of the great Mao famine, 1959-62, when some very large number of Chinese people starved to death—a number so large it is not known even to the nearest ten million. You can imagine how it was in the camps. The prisoners were fed buns made of sawdust, which generally killed them. The more savvy ones picked wheat grains and worms out of animal dung.

Those seven years included the period of the great Mao famine, 1959-62, when some very large number of Chinese people starved to death—a number so large it is not known even to the nearest ten million. You can imagine how it was in the camps. The prisoners were fed buns made of sawdust, which generally killed them. The more savvy ones picked wheat grains and worms out of animal dung.

North Korea was already notorious as the furthest extreme of totalitarian brutality, but there was no real camp literature at the time of my obsession. All I could find was an interview Amnesty International had done (still in their files, I see) with Ali Lameda, a Venezuelan communist who had worked as a translator in Pyongyang before coming under suspicion somehow and being sent to the camps for six years, 1967-73. Lameda was in solitary confinement most of the time, but he did encounter a few other prisoners, including a woman sent to the camps for smoking cigarettes. (Wipe that smile off your face, Mayor Bloomberg.)

From all these literary explorations thirty years ago, I picked up a few tips about camp life, which I hope will make my own incarceration easier.

Zeks never have enough, even absent the extremes endured by Pasqualini in the Mao famine. Scrounging food, knowing how to get better rations, secreting food about one's person—these are basic survival skills.

Study Varlam Shalamov's brief testament, if you can bear to.

Solzhenitsyn tells us that weedy intellectual types survived better in the camps than beefy peasant lads with nothing between the ears. Stock up on literature, history, mathematics. Arthur Koestler stayed sane in a Spanish civil war dungeon by mentally proving theorems about prime numbers. One of Shalamov's characters survives among common criminals by telling them stories from Russian literature to relieve their boredom. (The most sadistic regimes put "politicals" in among common criminals, who of course preyed on them mercilessly.)

If you're in fairly good shape, make a little trouble when first imprisoned. Let them beat you some, then show an improved attitude. Labor camp supervisors are bureaucrats, always on the lookout for something to put in the reports they write for their superiors. If they can write: "This Derbyshire was a real hard case when he first came in, but he's improved a lot," that reflects well on them.

This can be your path from latrine detail to camp librarian.

It needs to be carefully calibrated, though; making too much trouble can be fatal. It won't work, either, if you're in a type of camp where the object is just to work you to death. In a strongly ideological regime, though, the camp bosses may believe their own propaganda about transforming human nature; then you have an opening.

won't be a problem if the food is real bad: your metabolism will be too depleted. Otherwise just try not to think about it.

Not that opportunities may not arise. One of the better sex-in-the-camps stories comes from Bukovsky. In To Build A Castle he writes about being in a remote area of Siberia at a camp that sent prisoners out on work details. There were some peasant smallholdings nearby, and one of the peasants owned a goat which grazed free. Seeing this creature, the poor sex-starved zeks could not help themselves, so they helped themselves … to the goat.

Unfortunately the peasant's wife saw them. She ran back to the house screaming for her husband. "Ivan! Ivan! Come see what the prisoners are doing to our goat!"

Old Ivan ambles out, just as the zeks are running off into the distance. "We'll have to slaughter the goat!" wails his wife.

"Why?" asks Ivan.

"After what they did?" says Katya. "The beast is unclean! We must kill it!"

Ivan: "I don't see the necessity. I've been [deleted because of corporate censorware] you for forty years. I'm not going to kill you, am I?"

There you are: camp life can have its lighter side. I think I could cope.

It's the family that worries me. Under Stalin's code, there were severe social proscriptions against the wife and children of an Enemy of the People. Our coming despotism may take the same attitude.

Still, given enough advance warning, I can probably get my own wife and kids out to the comparative sanity and freedom of China.

John Derbyshire [email him] writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him. He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire's writings at VDARE.com can do so here.