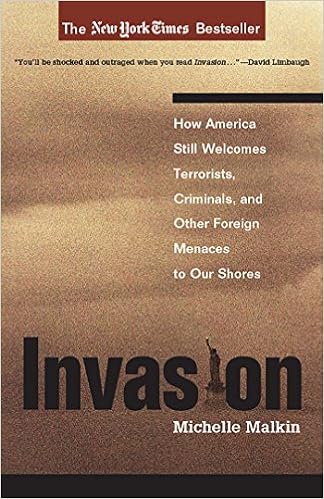

Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists, Criminals, and Other Foreign Menaces to Our Shores, by Michelle Malkin (Regnery, $27.05)

[VDARE.COM NOTE: Immediately after this review appeared in the first (October 7) issue of The American Conservative James Taranto attacked it in OpinionJournal, See Peter Brimelow's reply. Taranto reacted angrily (scroll down to third item from end); we post Peter Brimelow's further comments here.]

Nasty things seem to happen to people who write critically about immigration [PB comment: which is why Scott McConnell is editing TAC and I'm running VDARE.COM]. Accordingly, the small catacomb of immigration reformers–so similar to the persecuted minority that constituted the American conservative movement thirty years ago–is very worried for Michelle Malkin.

Nasty things seem to happen to people who write critically about immigration [PB comment: which is why Scott McConnell is editing TAC and I'm running VDARE.COM]. Accordingly, the small catacomb of immigration reformers–so similar to the persecuted minority that constituted the American conservative movement thirty years ago–is very worried for Michelle Malkin.

This young Filipino-American woman has made a remarkable debut as a conservative syndicated columnist. She is already in nearly 100 newspapers, including The Washington Times, the New York Post and the Miami Herald. But she has recently begun to specialize in detailed and devastating exposés of the shambles that passes for U.S. immigration policy. Such is the political correctness of establishment journalism, both left and right, that this makes Malkin virtually unique. She has even attacked, for its blind support of amnesty for illegals, the Wall Street Journal Editorial Page, the Great Cham of the conservative establishment, which does not take such lèse-majesté lightly.

Doesn't she know what's good for her?

Apparently not. Malkin's new book, Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists, Criminals, and Other Foreign Menaces to Our Shores, by Michelle Malkin (Regnery, $27.05) is an important addition to the literature. It may not advance her career. But it is a signal service to her country.

Tolstoy famously said that all happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Pretty much the same is true of immigration books. Pro-immigration books–for example Joel Millman's The Other Americans or Sanford J. Ungar's Fresh Blood (click here for Peter Brimelow's review) are invariably triumphalist, anecdotal, larded with celebrations of the authors' own forbears from Russia, and fatally light on data. In contrast, anti-immigration books are much more diverse, and often highly technical. Sometimes, as in the case of Roy Beck's The Case Against Immigration, they even are at pains to reject the sobriquet "anti-immigration," arguing correctly but vainly that no-one wants to shut the borders completely, merely to correct glaring flaws in current policy. (Needless to say, this makes no difference to immigration enthusiasts in the establishment media. All critics of immigration policy are routinely labeled "anti-immigrant"–even when, as in my own case, they are immigrants themselves.)

The reason for this systematic difference goes beyond the usual sloth, stupidity and assorted other vices endemic in journalism, although these are certainly in evidence. Immigration is a new issue in American politics. It simply did not exist in its current form until the 1965 Immigration Act unexpectedly rekindled mass immigration after a forty-year lull. What American debate is experiencing is a classic paradigm shift, with the old pro-immigration orthodoxy being undermined by new facts and by new analysis derived from those facts.

The current crop of politicians and pundits generally spent their formative years in the mid-twentieth century immigration lull. Most of them are simply too old to recognize the new reality. In this respect, it is significant that Michelle Malkin was born only in 1970, two years after the 1965 Act took effect. Like Marxism, with which it has some odd similarities, dogmatic immigration enthusiasm may well be undermined in the end, not by the force of rational argument, but by relentless generational shift.

Malkin's unique angle on immigration policy is in effect a direct answer to the Wall Street Journal's damage-control maneuvers after last September's terrorist attacks. Writing on the Opinion Journal website on January 15, James Taranto gloated that

"You'd think a horrific sneak attack by 19 foreigners on American soil would be a perfect opportunity for the close-the-borders crowd, but they've scarcely been heard from. [This is an in-joke reference to the Wall Street Journal's notorious refusal to print contrary viewpoints on immigration, even from fellow-conservatives.] Of course, their argument wouldn't really stand up; it's preposterous on its face to suggest that Mexican gardeners are a national-security threat, even if Arab flight students are."

Malkin's response: it's the process, stupid. By focusing tightly on the way in which foreigners are admitted to the U.S., she demonstrates in crushing detail what 9/11 made clear to all observers less committed than Taranto: the process has collapsed. Whether the applicants are visitors or immigrants, and quite apart from any issue of security or economic benefit, the plain fact is that U.S. government agencies have lost their ability to guard the gates–let alone evict any undesirable who has actually entered.

The beauty of Malkin's approach is that it completely bypasses the vast questions in which the immigration debate often bogs down–such as how many immigrants should come in (i.e. should the government in effect second-guess Americans' decision to stabilize their population) and who (should the historic American nation be transformed by massive immigration from non-traditional sources).

Of course, these questions still have to be answered. But, Malkin says in effect, whatever your answer, you still have to enforce it through the admissions (and deportation) process. And, right now, that can't be done.

Thus Malkin notes that, of 48 Islamic militants involved in terrorist conspiracies during the last decade, only sixteen were here "legally" on temporary visas as students, tourists or business travelers. (She could have added that even these were technically illegal because they had not admitted the real purpose of their visit was to fly airliners into buildings etc., something the U.S. vetting process failed to pick up.) Seventeen were permanent residents or citizens (obviously another vetting failure). Twelve were illegal immigrants. The others had applied for political asylum or been granted amnesty after illegal stays. In all, twenty-one had violated U.S. immigration law at some point.

If that's not enough warning that the system is broke, Malkin points out, the Immigration and Naturalization Service actually mailed student visa approval notices to two of those "legal" entrants, Mohamed Atta and Marwan Al Shehhi, six months after they had died in the September 11 attacks. "I could barely get my coffee down," President Bush blustered when he heard the news. Nevertheless, his Administration stood by as higher education lobbyists shouted down Senator Diane Feinstein's proposal for a temporary moratorium on student visas to re-establish control.

A million foreigners have been admitted to the U.S. on student visas. The government has no idea how many are really studying.

Immigration policy, in Malkin's meticulous analysis, is basically driven by special interests and bureaucratic inertia. Higher education is one such special interest. The travel industry–aided by Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle's wife Linda, a lobbyist–is another. Pressure for faster handling of paperwork is intense, with the result that at least one 9/11 hijacker came through John F. Kennedy Airport with obviously incomplete documentation. Malkin prints a memo from an official at Los Angeles International directing inspectors not to respond to requests from airlines to vet suspected illegal immigrants and not to make disruptive group arrests even in the case of "suspected terrorists, kidnapping, slavery…" The memo is dated February 12, 2002.

The INS is manifestly on the wrong side in all this. To some extent, the agency's functioning seems to have become an end in itself. Malkin reports that in the six months after 9/11, it ground out another 50,000 tourist, business and student visas to non-Israeli visitors from the Middle East and another 140,000 to visitors from al-Qaeda havens in South Asia, apparently without any thought of security. Additionally, senior INS officials have quite clearly gone native to an extraordinary degree–"it's not a crime to be in the U.S. illegally," said INS deputy director Fred Alexander last year. (As Malkin patiently documents, it is.)

Malkin has changed my own thinking on the INS. I had always assumed, in my reasonable way, that the INS was a victim of poor laws and proliferating workload. Malkin reports enough management failure and corruption (involving at least one official I interviewed for my own immigration book, Alien Nation) to convince me that the problem is systemic.

As she says, how come the federal government can do instant background checks on law-abiding American gun buyers–but not when it catches illegal immigrants?

(The laws are poor, though. Malkin recounts the denouement of the 1996 Citizenship USA scandal, in which the Clinton White House pressured the INS to naturalize some 1.3 million immigrants–i.e. instant Democrats–without adequate background checks. The Justice Department subsequently tried to revoke the citizenship of some 6.300 who turned out to be felons but was blocked on appeal. The judge invited Congress to step in–but it did not, despite Republican control.)

I would have liked to see Malkin apply her method to disease, which, like terrorism, is a wild card in the current immigration debate. Screening immigrants for disease was constant even at Ellis Island, and significant numbers were rejected. But today, the U.S. is arguably more exposed to immigrant-born disease than ever in its history, if only because of illegal border crossings. Tuberculosis has already reappeared. West Nile may have been immigrant-imported. Awful things are being incubated in the vast human petri dishes created by Third World urbanization. And they're coming here–unless they're stopped.

But Malkin makes a more immediately dramatic point: she summarizes the story of Angel Resendiz, the "Railway Killer," a Mexican who repeatedly entered the U.S. illegally over a 25 year period, had at least 25 encounters with U.S. law enforcement, was deported three times and "voluntarily returned" at least four times, and who, between 1997 and 1999, is known to have who murdered at least 12 Americans–the last four after being released by the INS, although there were already warrants outstanding for his arrest.

This story, complete with harrowing vignettes of Resendez' archetypical Middle American victims, is a classic piece of journalism. It is a disgrace to the establishment media that it could never appear there.

Resendiz liked to fracture his women victims' skulls and rape them as they died. Their terrible deaths are on James Taranto's head–and on the heads of every single immigration enthusiast who has minimized this mortal threat to America.

Peter Brimelow is the author of Alien Nation: Common Sense About America's Immigration Disaster and Editor of VDARE.com.

October 11, 2002