John J. Miller was described as "the most unscrupulous of contemporary immigration enthusiasts" by Peter Brimelow in the new Afterword to Alien Nation because of his uninhibited habit of simply lying about statistics and what his opponents were actually saying. Miller's hiring by National Review immediately after John O'Sullivan firing as editor in 1999 was a clear sign that owner William F. Buckley had caved on immigration reform. At VDARE.COM, we started a "Miller Watch" series to keep him line. We succeeded too well, because he stopped writing about immigration altogether. Now it appears he has transferred his technique to diplomatic history.

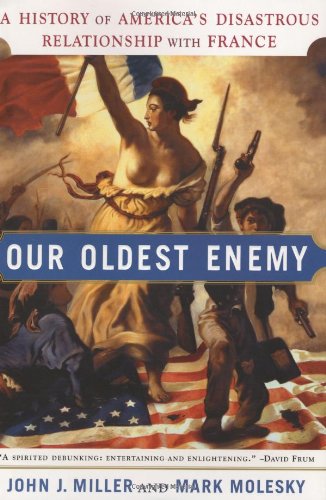

One word I can think of to describe Miller and Mark Molesky's book Our Oldest Enemy: A History of America's Disastrous Relationship With France is vulgar. Another is naïve. Still another is just plain silly. [Vdare.com Note: Foreign Affairs Magazine likes "shoddy and biased"]

One word I can think of to describe Miller and Mark Molesky's book Our Oldest Enemy: A History of America's Disastrous Relationship With France is vulgar. Another is naïve. Still another is just plain silly. [Vdare.com Note: Foreign Affairs Magazine likes "shoddy and biased"]

Miller and his co-author (an old school chum who teaches history at Seton Hall University), are very angry with France and with the French. The proximate reason is President Chirac's opposition to the Iraq War. An amazing list of more distant reasons is also adduced, ranging from the French-Indian Wars of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the XYZ and Citizen Genet Affairs of the 1790s, Napoleon's insults to the young American republic, Napoleon III's contemplated support of the Confederacy and his invasion of Mexico (perhaps if he'd won, the Border Patrol would today be arresting Frenchmen in berets along the U.S.-Mexican border?), Clemenceau's bamboozling of President Wilson at Versailles, Jean-Paul Sartre, Charles De Gaulle, and Deconstructionism.

Only at the conclusion of the book, with its coy references to the French people's "historic levels of anti-Semitic sentiment" and the French government's failure "to grapple with a rising tide of anti-Semitic sentiment," are we given a hint at what is really eating the authors.

Miller and Molesky have chosen such a long and improbable way around to make their point (somewhat on the order of attacking Iraq in order to defend the United States) that somehow we have ceased to care when finally they get around to it.

Like An End to Evil by Richard Perle and Miller's colleague at National Review, David Frum, Our Oldest Enemy comes just a few months too late to deliver whatever conviction it might ever have carried. Trying to make Jacques Chirac a villain when he deserves rather to be treated as a prophet and a hero, having his health toasted in Beaujolais nouveau from the Azores to the Danube, is as absurd as it is childish.

There are no demonstrations in Paris or Berlin demanding that the French and German governments revisit their decision against sending troops to reinforce President Bush's Grand Coalition in Iraq. On the contrary, Spain's conservative government has been ousted for signing on with the United States, Berlusconi's in Italy is threatened, and Tony Blair's is a shambles.

If anything remains to be said about M. Chirac in this regard, it is that he has behaved in a gentlemanly way during the course of the American debácle in Iraq, never once giving rein to what must be the certain temptation to say, "I told you so." For some people, it seems, civility is simply not an ordeal.

Meanwhile, concerning this "oldest enemy" business, a few thoughts at random:

France was, in fact, playing what came in the late nineteenth century to be called the Great Game. (Miller & Molesky admit as much in their discussion of France's role in aiding the American revolutionists.) If the authors believe the World's Sole Superpower they are eager to defend at every turn is not engaged today in a Great Game of its own, they have no business writing about world politics at all.

Molesky & Miller are offended by a nineteenth-century French author who described Americans as

"a people of ignorant shopkeepers and narrow-minded industrialists, who do not have on the whole surface of their continent a single work of art…who do not have in their libraries a single science book not written by the hand of a foreigner; who do not have a single social institution not patterned after an ancient one, and constituting a flagrant rebuttal of the Christian principle it pretends to emulate."

Well, well; fighting words to be sure. But for a truly effective putdown of the American people in the first half of the nineteenth century, however, one ought to consult Domestic Manners of the Americans by Frances Trollope (mother of Anthony). Her English hauteur and disdain remains unmatched by any Frenchie I know of.

While the French elite may have had little affection or respect for the United States, the same was true of all the other aristocratic European powers.

Admittedly, France has harbored a special animus against the United States for having pioneered mass culture. But who can blame it?

Nothing personal—or discriminatory! They have just always regarded la France as being truly God's country, and French culture as the residuum of every noble and civilized element in history, like the Heavy Dragoon in Gilbert & Sullivan's Patience.

And who are Miller & Molesky to complain?

The Girondins, they charge, "subscribed to the very immoderate program of overthrowing monarchs everywhere. Their slogan was 'War with all kings and peace with all peoples.'"

Elsewhere, M&M mock the French belief in France's ability to change the world.

Here is a spectacular example of how fanaticism blinds men to themselves, as well as to other men. Neocons are supposed to be smarter than the rest of us. But do they really know what they are saying most of the time? In respect of the Iraq War, John Miller and Mark Molesky—not the much-maligned Jacques Chirac—have identified themselves as ideological heirs of the Girondins.

But at least the Girondins were French patriots. In urging on an imperial war, while simultaneously supporting nation-dissolving immigration at home, M&M raise real questions as to where their own loyalties lie.

Chilton Williamson Jr. [email him] is the author of The Immigration Mystique: America's False Conscience and an editor and columnist for Chronicles Magazine, where he writes The Hundredth Meridian column about life in the Rocky Mountain West. His latest book is The Conservative Bookshelf: Essential Works That Impact Today's Conservative Thinkers.