Earlier by John Derbyshire: Dinkins-Bradley Effect In German Elections—Germans Didn't Want To Tell Pollsters How "Far-Right" They Were Trending

A frustrating feature of the Trump Era is the steady stream of headlines gloating that Americans still do not see the immigration-driven demographic disaster on the horizon. “Despite Trump’s and Tucker Carlson’s efforts, nativism is losing,” proclaims the Washington Post [The Fix, by Aaron Blake, July 15, 2019] “Support for immigration is surging in the Trump era,” crows Matthew Yglesias [Email him / Tweet him ] at Vox (although admitting the effect is heavily concentrated among white Democrats.) [Vox, July 5, 2018] But a large body of research shows these numbers are substantially overstated.

The problem is not just a matter of how the polling questions are worded, although that is often a concern. No, there is a much simpler explanation for this apparent trend in American attitudes:

They’re lying.

“Social Desirability Bias” is the term for the tendency of survey respondents to bend the truth and answer questions in a socially acceptable manner. There are a variety of methods for measuring this Social Desirability Bias, including differential response rates on web-based surveys versus in-person interviews. (People are more likely to be honest in private.)

One of the most widely accepted, however, is the “List Experiment.” Survey respondents are randomly divided into two groups. One group is given a list of statements, none of which are socially sensitive, and asked how many they agree with rather than which ones. A second group is given the same list, but with a sensitive issue added to the mix. The true feelings of the whole group on the sensitive question are found by comparing the difference between the two cumulative results statistically.

List experiments have long been used to measure honest opinions on a wide variety of socially sensitive topics such as drug use, sexual activity, and opinions about sensitive issues such as race and religion. [Examples of List Experiments, Kosuke Imai's Homepage, Harvard.edu]

Unsurprisingly, given the increased centrality of the issue, questions about demography and immigration have received more attention in recent years. The results have repeatedly indicated that such questions are substantially affected by Social Desirability Bias.

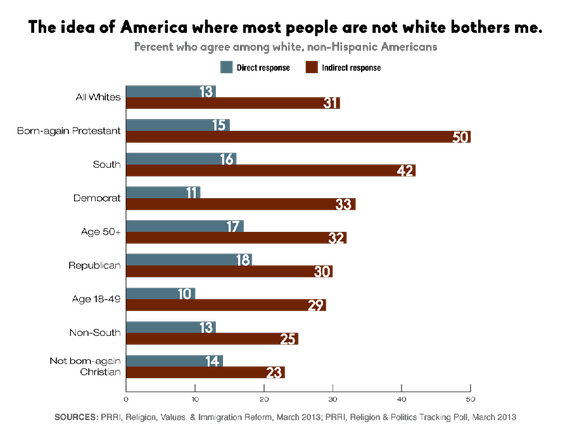

One list experiment conducted in 2013 asked white respondents whether “the idea of America where most people are not white” bothered them. When asked directly, only 13 percent agreed (see below), but in the list experiment the real percentage was 31 percent, a full 18 percentage points higher. Interestingly, the study found that white Republicans were more willing to admit their feelings openly (18 percent were bothered vs. only 11 percent of white Democrats), but when asked indirectly white Democrats were actually more bothered (33%) than white Republicans (30%).

Hidden Racial Anxiety in an Age of Waning Racism, by Robert P. Jones, The Atlantic, May 12, 2014

Similar results were found in another list experiment that explored white support for reducing immigration. The Influence of Social Desirability Pressures on Expressed Immigration Attitudes, by Alexander Janus, Social Science Quarterly, October 25, 2010. When asked directly, 42 percent indicated that they supported “cutting off immigration to the United States.” But under the cloak of anonymity, that number rose to 61 percent, an increase of 19 percent. Once again, the gap was highest among liberal and college-educated whites.

Similar results were found in another 2015 study of Americans and a 2018 study in Europe .

This gap between openly expressed and private sentiments should not surprise anyone who has observed the frequent disconnects between polling results and real life. Recent research by Ryan Enos [Email him], a Harvard political scientist, has shown that white liberalism frequently waivers or collapses when confronted with the consequences of diversity. [How Much Can Democrats Count on Suburban Liberals?, by Thomas B. Edsall, NYT, June 14, 2018]

When polled, for example, fewer than one in five whites will admit that they would not want to live in a half-black neighborhood. [28 percent of whites say they favor a law allowing homeowners to discriminate, by Emily Badger, Washington Post, July 9, 2015] This figure has been trending in a progressive direction for decades. But this trend supposedly more progressive views has not been matched by the trend in housing, where de facto segregation has been increasing.

A majority of white parents say they prefer racially integrated schools. [New Poll Data Underscore Better Ways to Talk about School Integration, by Halley Potter, TCF.org, September 7, 2017] But in the real world, schools are also becoming more de facto segregated When pressed, white liberals will fight tooth and nail to prevent genuine diversity in their children’s schools.

Given the obvious gaps between our stated beliefs and actions, the only real surprise is that such polling results are still taken at face value.

This disconnect should also raise questions about the more recent liberalization of white racial views [The Rising Racial Liberalism of Democratic Voters, by Sean McElwee, NYT, May 23, 2018], which is sometimes referred to as the Great Awokening, and which seems to have accompanied parallel changes in immigration opinion. [Majority of Americans continue to say immigrants strengthen the U.S., by Bradley Jones, Pew Research, January 31, 2019]

Are these trends genuine or are they the result of increased societal pressures exerted by the media and social media [The Democratic Electorate On Twitter Is Not The Actual Democratic Electorate, by Nate Cohn and Kevin Quealy, NYT, April 9, 2019] and a reflexive backlash against Donald Trump? Authentic changes in social values often take many years or even generations to manifest themselves. The suddenness of the Great Awokening suggests that it may be largely, if not entirely, an artifact of Social Desirability Bias.

Social Desirability Bias does not explain everything, of course. Research has not uncovered a similarly large gap between election polls and voting results, at least not yet.

One analysis of the 2016 election by Morning Consult, a polling firm, did find modest evidence of Social Desirability Bias among college-educated voters, who appeared to be more supportive of Donald Trump in web-based surveys. [How We Conducted Our ‘Shy Trumper’ Study, by Kyle Dropp, November 3, 2016] But subsequent analyses by both 538.com [‘Shy’ Voters Probably Aren’t Why The Polls Missed Trump, by Harry Enten, November 16, 2016]and a post-election polling consortium found little evidence in the actual election returns. List experiments also found modest [Social Desirability Bias and Polling Errors in the 2016 Presidential Election, SSRN, July 12, 2017] or no impact. [Did Shy Trump Supporters Bias the 2016 Polls? Evidence from a Nationally-representative List Experiment, by Alexander Coppock, Yale, ISPS, June 26, 2017] Trump’s unexpected victory seems to have been a combination of increased white working-class turnout and its impact on key states. Whether this will still be true in 2020—and whether Social Desirability Bias will start to distort national polling, as it probably already distorts Trump’s Favorability rating—remains to be seen.

For now, it is sufficient to say that polls on racial attitudes, including those related to immigration, appear to be either wrong or substantially overstated.

This, in turn, raises a final possibility: Social Desirability Bias is ultimately a product of social conformity, which can sometimes lead to what sociologists call a “Conformity Trap.” Conformity Traps occur when members of society, either out of fear or ignorance, fail to challenge unpopular social norms or power structures. One well-known aspect of Conformity Traps, however, is that when they do come to an end, it is often sudden and unexpected—as I argued in How White Liberals Will Wake Up, Unz.com, April 8, 2019.

This, in turn, raises a final possibility: Social Desirability Bias is ultimately a product of social conformity, which can sometimes lead to what sociologists call a “Conformity Trap.” Conformity Traps occur when members of society, either out of fear or ignorance, fail to challenge unpopular social norms or power structures. One well-known aspect of Conformity Traps, however, is that when they do come to an end, it is often sudden and unexpected—as I argued in How White Liberals Will Wake Up, Unz.com, April 8, 2019.

Notable examples of Conformity Traps: the silence surrounding Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein before they were outed. In the political realm, they include the unexpected cascade of events that led to the Arab Spring and the fall of Communism.

In a seminal paper entitled "Now Out of Never: The Element of Surprise in the East European Revolution of 1989," World Politics, October 1991, Timur Kuran wrote about the central importance of conformity and lies in propping up the Communist regimes of the era:

The system was sustained by a general willingness to support it in public: people routinely applauded speakers whose message they disliked, joined organizations whose mission they opposed, and signed defamatory letters against people they admired, among other manifestations of consent and accommodation.

"The lie," wrote the Russian novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn in the early 1970s, "has been incorporated into the state system as the vital link holding everything together, with billions of tiny fasteners, several dozen to each man." If people stopped lying, he asserted, communist rule would break down instantly.

He then asked rhetorically, "What does it mean, not to lie?" It means "not saying what you don't think, and that includes not whispering, not opening your mouth, not raising your hand, not casting your vote, not feigning a smile, not lending your presence, not standing up, and not cheering.”

Our present predicament is not so very different from these revolutionary periods of the past.

It may be only a matter of time before it is our turn to wake up from history.

Romania, 1991:

Right here, right now

there is no other place I want to be

Right here, right now

watching the world wake up from history

Patrick McDermott [Email him] is a political analyst in Washington, DC.