Here’s the kind of automation fail nobody wants to see. A jetliner crashed and killed all 189 people on board last month as the pilots struggled unsuccessfully to wrest control from the plane’s own computer system.

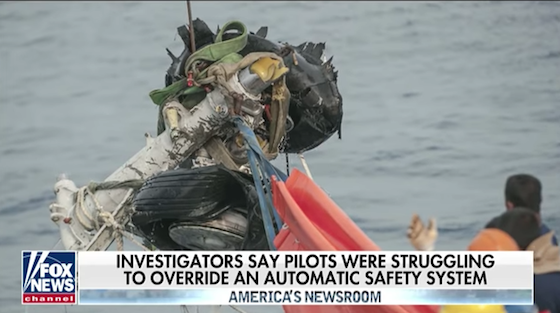

Below, debris recovery in the Java Sea.

It’s not the first time the mismatch between airliner computers and human pilots caused loss of life. On July 6, 2013, an Asiana plane from Korea hit the seawall at the edge of the San Francisco Airport runway on approach and crashed, killing three and injuring dozens. One important factor was the dependence of the pilot on the jet’s automation and unfamiliarity with flying the plane personally. In fact, a 2013 study from the FAA found that in general, pilots depend too much on automated flight systems, and many now don’t have the skill to handle the plane by hand.

Both crashes show that the transition to the automated future is not entirely smooth or even safe. Self-driving cars were created with the idea of being far safer than those with humans behind the wheel. Still, last March a self-driving Uber failed to perceive a woman who was walking her bicycle across a highway in Tempe, Arizona, causing her death. The technology we have today is not yet up to the trust many invest in it.

Wednesday’s front-page New York Times article about the recent jetliner crash was reprinted in Australia’s Canberra Times:

Lion Air black box reveals fatal man-machine tug-of-war to save plane, By James Glanz, New York Times, November 28 2018

New York: Data from the jetliner that crashed into the Java Sea last month shows the pilots fought to save the plane almost from the moment it took off, as the Boeing 737’s nose was repeatedly forced down, apparently by an automatic system receiving incorrect sensor readings.

The information from the flight data recorder, contained in a preliminary report prepared by Indonesian crash investigators and scheduled to be released on Wednesday, documents a fatal tug-of-war between man and machine, with the plane’s nose forced dangerously downward more than two dozen times during the 11-minute flight.

The pilots managed to pull the nose back up over and over until finally losing control, leaving the plane, Lion Air Flight 610, to plummet into the ocean at 450 mph (724 km/h), killing all 189 people on board.

The data from the so-called black box is consistent with the theory that investigators have been most focused on: that a computerised system Boeing installed on its latest generation of 737 to prevent the plane’s nose from getting too high and causing a stall instead forced the nose down because of incorrect information it was receiving from sensors on the fuselage.

In the aftermath of the crash, pilots have expressed concern that they had not been fully informed about the new Boeing system — known as the manoeuvring characteristics augmentation system, or MCAS — and how it would require them to respond differently in case of the type of emergency encountered by the Lion Air crew.

“It’s all consistent with the hypothesis of this problem with the MCAS system,” said R. John Hansman Jr., a professor of aeronautics and astronautics and director of the international centre for air transportation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Boeing has said that the proper steps for pulling out of an incorrect activation of the system were already in flight manuals, so there was no need to detail this specific system in the new 737 jet.

In a statement on Tuesday, Boeing said it could not discuss the crash while it is under investigation but reiterated that “the appropriate flight crew response to uncommanded trim, regardless of cause, is contained in existing procedures.” (Continues)