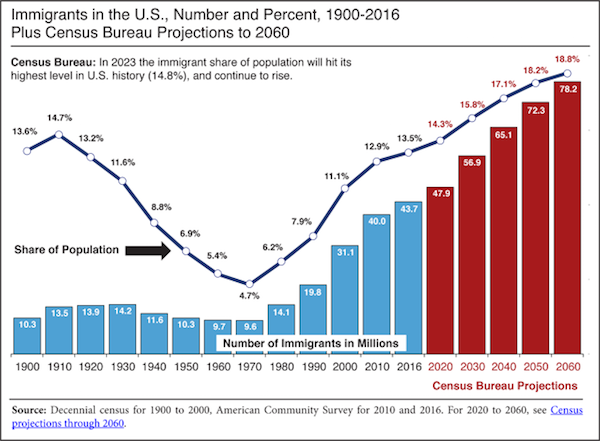

Tuesday’s New York Times front page includes an article titled “Immigration By Legal Path Begins to Fall” showing how President Trump’s efforts to reduce the foreign influx into America has begun to turn the tide.

We know already that Trump’s Remain in Mexico deal has severely chilled the asylum fraud since fewer than one percent of scammers have been admitted after the new procedure was implemented. For a few years previous, every illegal alien was a “victim” and therefore eligible for asylum, but that’s pretty much over under the current administration.

But the decrease of legal immigration is a surprise, since the world population continues to grow and will reach 8 billion in a few years. So push factors remain, but apparently it makes a difference when the occupant of the White House is not dedicated to maximum foreigner influx.

Still, the future lies ahead, and it looks less American for us US citizens. The best thing to do would be to end immigration entirely for many reasons.

Robots and AI will be doing millions of jobs in a few years so we won’t need immigrants for those occupations. Seriously, automation makes immigration obsolete.

Having millions of foreign residents has no advantage other than perhaps restaurants, and that’s hardly a reason to continue immigration — I’d rather eat boiled potatoes and burnt hamburger.

Some areas have become Spanish-speaking zones where you might as well be in Mexico or Cuba. And language diversity is not a plus, it’s a danger when you don’t know what’s going on.

California seems headed for another drought, judging from a painfully dry winter, so we don’t need to import any more water-users here — 39 million is more than enough.

So having fewer immigrants of any sort is a win for all Americans. Let the foreigners fix their own countries as they once did. Double win.

Here’s a reprint of the New York Times article:

As Trump Barricades the Border, Legal Immigration Is Starting to Plunge, New York Times, February 24, 2020

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s immigration policies — from travel bans and visa restrictions to refugee caps and asylum changes — have begun to deliver on a longstanding goal: Legal immigration has fallen more than 11 percent and a steeper drop is looming.

While Mr. Trump highlights the construction of a border wall to stress his war on illegal immigration, it is through policy changes, not physical barriers, that his administration has been able to diminish the flow of migrants into the United States. Two more measures took effect Friday and Monday, an expansion of his travel ban and strict wealth tests on green card applicants.

“He’s really ticking off all the boxes. It’s kind of amazing,” said Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan research group. “In an administration that’s been perceived to be haphazard, on immigration they’ve been extremely consistent and barreling forward.”

The number of people who obtained lawful permanent residence, besides refugees who entered the United States in previous years, declined to 940,877 in the 2018 fiscal year from 1,063,289 in the 2016 fiscal year, according to an analysis of government data by the National Foundation for American Policy. Four years ago, legal immigration was at its highest level since 2006, when 1,266,129 people obtained lawful permanent residence in the United States.

And immigration experts say new policies will accelerate the trend. A report released on Monday by the foundation projected a 30 percent plunge in legal immigration by 2021 and a 35 percent dip in average annual growth of the U.S. labor force.

Trump administration officials have said that immigration into the country should be based on merit and skills, not the family-based system that for decades has allowed immigrants to bring their spouses and children to live with them.

“President Trump continues to deliver on his promise to the American people to enforce our nation’s immigration laws,” Kenneth T. Cuccinelli, the acting secretary of homeland security, wrote in The Hill, a Capitol Hill newspaper, on Monday.

The rapid declines come as record-low unemployment has even the president’s acting chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney, confiding to a gathering in Britain that “we are desperate, desperate for more people.”

But the doors have been blocked in multiple ways. Those fleeing violence or persecution have found asylum rules tightened and have been forced to wait in squalid camps in Mexico or sent to countries like Guatemala as their cases are adjudicated. People who have languished in displaced persons camps for years face an almost impossible refugee cap of 18,000 this year, down from the 110,000 that President Barack Obama set in 2016.

Family members hoping to travel legally from Iran, Libya, Syria, Yemen and Somalia were blocked by the president’s travel ban.

Increased vetting and additional in-person interviews have further winnowed foreign travelers. The number of visas issued to foreigners abroad looking to immigrate to the United States has declined by about 25 percent, to 462,422 in the 2019 fiscal year from 617,752 in 2016.

And two more tough policies have now taken effect. The expansion of Mr. Trump’s travel ban to six additional countries, including Africa’s most populous, Nigeria, began on Friday, and the wealth test, which effectively sets a wealth floor for would-be immigrants, started on Monday. Those will reshape immigration in the years to come, according to experts.

The travel and visa bans, soon to cover 13 countries, are almost sure to be reflected in immigration numbers in the near future. Of the average of more than 537,000 people abroad granted permanent residency from 2014 to 2016, including through a diversity lottery system, nearly 28,000, or 5 percent, would be blocked under the administration’s newly expanded travel restrictions, according to an analysis of State Department data.

But the wealth test — or public charge rule — may prove the most consequential change yet. Around two-thirds of the immigrants who obtained permanent legal status from 2012 to 2016 could be blocked from doing so under the new rule, which denies green cards to those who are likely to need public assistance, according to a study by the Migration Policy Institute. (Continues)