Automation is coming on strong in the economy and will take millions of jobs in the next few years because as soon as a machine becomes cheaper for an individual task than a human, the worker will be gone. In addition, business owners like how robots work 24/7 and don’t require lunch, sleep or paychecks. Just an occasional squirt of oil will suffice to keep the machines performing.

More recently, the Wuhan pandemic has speeded up the process of businesses adopting smart machines, since robots also don’t get sick—so convenient rather than undependable humans with their annoying germs.

CNBC held a discussion among tech experts last month about smart machines in the Plague Year: How coronavirus could usher in a new age of automation:

There’s not a lot that can be done to deal with the job-killing Age of Automation we face, but it would make sense to end immigration, because most of the jobs that immigrants do can be done more cheaply by smart machines. In short,

Automation Makes Immigration Obsolete

Here’s a transcript of the discussion I cleaned up for easy reference:

NARRATOR: Automation is coming for your job — at least that’s the fear among many workers — from burger-flipping bots to car-building robots, not to mention high-powered software taking on more and more administrative tasks. It seems like hundreds of skills are rapidly becoming obsolete in the US economy. A McKinsey study found that AI and deep learning could add as much as $3.5 trillion to $5.8 trillion in annual value to companies.

ANDREW YANG: Eighty percent or more of the jobs that make $20 an hour or less are at least potentially subject to automation.

NARRATOR: The economic shock of the pandemic hasn’t helped; human workers are vulnerable to diseases that robots aren’t, making it much easier and now cheaper to have a robot on staff that doesn’t require healthcare.

MARCUS CASEY: Businesses are kind of looking and seeing that humans can get sick from covid, but machines can’t.

MICHAEL HICKS: If you can eliminate the healthcare costs, the labor and wage tag that comes along with those folks and particularly in services — that’s a big competitive advantage.

NARRATOR: To put the increase in robotics in perspective: the U.S. had .49 robots per thousand workers in 1995 which rose to 1.79 robots per thousand workers in 2017, but automation isn’t just a robotics revolution. The rise in information technology and artificial intelligence or AI has also become an enabler of automation. AI can help navigate difficult challenges that previously only a human operator could handle. Of course, if you’ve encountered automated phone systems, it’s likely you personally experienced that automation still has a long way to go.

DARON ACEMOGLU: There’s nothing wrong with automation as long as it is part of a portfolio of technological changes, but its specific effects are not super good for labor.

NARRATOR: But the pace of technological change is accelerating, and the covid-19 pandemic could have acted as the accelerant. The Urban Institute estimates more than 8 million low-income jobs have been lost during the pandemic.

ROBERT LITAN: One of the reasons we have friction in our labor force is that when people get laid off they have a harder time finding a new job, and that’s been especially true in the last twenty years.

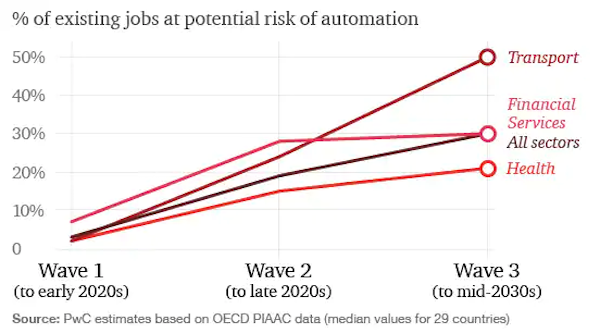

NARRATOR: High-skilled jobs such as finance managers, payroll managers and accounting roles face a 56 percent chance of being automated in the future. And according to Consulting.ca, up to 30 percent of oil and gas jobs could be lost to automation by 2040. One major problem in the US for workers is that workers are a tax burden for employers, whereas machines are actually subsidized.

ACEMOGLU: US tax code has been very automation friendly: the United States has always taxed capital more lightly than labor.

LITAN: I think the government is going to have to be more aggressive going forward than just simply relying on a growing economy.

NARRATOR: Automation was progressing before the pandemic hit, but the sudden financial pressure that businesses in the US encountered created the perfect storm to turn to automation. In previous recessions, enterprises looking to streamline their business practices turned to automation and in some cases the recession simply sped up what was already a long desired change.

LITAN: The conventional wisdom about the pandemic is that it has greatly accelerated all kinds of trends — AI, artificial intelligence, robotics and things like that — the movement toward those is certainly going to be accelerated post-pandemic for a simple reason: robots don’t get sick.

NARRATOR: In food service industries, industrial machines that helped with food packaging preparation or even serving have helped to ease the burden on human employees who are susceptible to disease. Companies are looking to vaccinate their supply chains to make them more efficient. Automation of processes helps to eliminate the need for more administrative staff and a less human-labor-reliant warehouse system means that when a co-worker calls in sick, half the office isn’t quarantined.

CASEY: Among those who are actually employed in some of these low-wage occupations in the future they’ll be downward pressure on their wages, right, because they’ll be competing with machines, and so I think there will be some competition there.

LITAN: If we’re not able to retrain people for new things, then the historical pattern has been that the people that benefit the most from automation are people that have IT skills. In the post-pandemic world, if you don’t have some IT skills you’re at greater risk of being disrupted and having your wages fall relative to other people.

NARRATOR: Both the Trump administration and the Biden campaign have proposals to advance job gains for workers that have become affected at least in part by automation.

JOE BIDEN: Whether your predictions are true about automation and self-driving trucks, these folks aren’t stupid: they listen, they understand and they’re scared to death.

LITAN: The Biden campaign has proposed making community college free and also providing money for apprenticeships. The Trump administration has advocated more money for apprenticeships and so forth, but I think as a society the need to help people transition to new jobs is going to be much greater in the post-pandemic world than the one that existed just six months ago.

NARRATOR: The key to a post-pandemic world is a vaccine for covid-19. Recent vaccine candidates have continued forward in clinical trials, and there is hope that if the US can field a vaccine quick enough, the economic recovery could slow down some automation trends that have spiked due to the outbreak.

LITAN: But I don’t think enough thought has been given to how to get enough people — and I think it may take as many as 80 percent — enough people in the population to take the vaccine, so that we can get herd immunity and get our economy back to normal. And then these trends that we’re talking about — the AI trends and automation — they’ll kick in later, but we need to get back to normal before we even get to the so-called longer term trends.

NARRATOR: The clock can’t be turned back on technological advancement. AI research is steadily increasing and US investment ranged between 15 billion to 23 billion in 2016 alone.

HICKS: In the long run you know, better productivity leads to more economic growth, leads to higher wages for everybody. So there’s really no doubt in the long run automation, the story of it for the past 300 years, has been a happy one. In the short run for workers who are displaced, we generally don’t see wages recover, certainly not quickly. We see more effects transmitted to their families as well —more problems finishing school or behavioral issues.

NARRATOR: According to a Deloitte study, 50 percent of all jobs are potentially open to automation in the coming decades and according to McKinsey, 400 million workers could be replaced by automation by 2030 which is about 15 percent of the global workforce. Automation isn’t all doom and gloom; some are hopeful that if automation takes over lower skilled tasks, it could open up opportunities for fewer work hours and more free time that could be focused on creative pursuits that could actually result in even more economic growth.

CASEY: There’s certainly ways that the government can kind of step in and actually support the reskilling of workers who’ve lost their jobs — right, you know they can form public-private partnerships, support people going back to school or investing in more specialized skill sets within industries, help them move across industries from areas that have been hit hard by the pandemic to sort of more emerging areas. So that’s one set of policies. The other set of policies is to actually provide incentives for firms to actually do a lot of this work themselves.

HICKS: Well in general, automation is important because it brings higher productivity to workers, and it allows us to do more at lower costs. And so in general on average, it’s going to be a great boom to us. The challenge I think is during the transition, both for individual workers and the communities in which they live you could see some disruption from this, particularly I think among lower income or less well trained workers who have fewer skills to transition in an automated environment.

NARRATOR: One proposal to help offset job loss from automation is the concept of universal basic income or UBI.

YANG: The freedom dividend makes the case to our fellow Americans that we all have intrinsic value as people, as citizens, as human beings.

NARRATOR: Some UBI plans include a roughly $1000 monthly payment to every adult in the country with no strings attached. Detractors have argued that UBI would cause a drop in economic activity because it would disincentivize work. Other arguments contend that it is not feasible financially for the US government to dole out large sums of money to such an extreme number of citizens.

LITAN: We’ve done sort of a temporary UBI in the course of this pandemic, you know we sent out the $1200 check, or as we talk now, Congress is debating whether to send out another one. I don’t think that’s permanently sustainable from a fiscal point of view.

NARRATOR: Finland recently ran a UBI study and concluded that it did not create a disincentive for citizens to work. The study compared 2,000 people on UBI versus 173,000 on unemployment benefits over a two-year period. People who were on UBI reported feeling better mentally about their well-being compared to those on unemployment benefits. Researchers also noticed that those on UBI saw a higher increase in employment but remained unsure on the causes behind that trend.

LITAN: I think handing out money to everyone regardless of their circumstances is simply going to cost too much, especially in the in the light of all the additional debt that we’ve taken on.

CASEY: And we might get a better bang for our buck than just you know giving out checks every month to people who haven’t lost their jobs because there’s also a you know externality effects associated with that. Right, most people I think want to work, they want to build human capital and that’s building our productive base going into the future. So it has a short-term static issue like during the pandemic. Yeah, I’m fine with that — having a short run sort of universal basic income because people can’t work because of the pandemic makes sense. I’m not sure yet, I mean I don’t think the evidence is quite in that this is a very viable long-term strategy relative to some of the other ways that we could invest that money.

ACEMOGLU: I think it’s too late to reverse job losses from automation in the same way that it’s too late to reverse the job losses that happened from say import competition from low-wage firms from China, but we can be forward looking and have a better strategy for dealing with the continuation of this.

NARRATOR: Older workers appear generally less able to pivot into new careers that require learning new skills.

HICKS: The challenge that we see isn’t a 23-year-old learning new technology; it’s a 43 or 53-year-old.

NARRATOR: Part of the problem could be the way our educational system is designed.

HICKS: I think a bigger challenge one that’s going to be more long-term though is to address educational issues early on so the the ability to transition tasks for adult workers is really a matter of middle school math and language arts, so if you focus on those sorts of skills to make sure that the children don’t go into their high school years unprepared, I think you’re really creating a class of workers that are better able to adjust to new technology.

NARRATOR: Up to 14 percent of the global workforce may be forced to change careers by 2030 because of automation.

LITAN: I’m an advocate of lifetime training accounts so that people could borrow and then pay back based on their income in order to get training certificates or certificates to qualify them for new jobs and so forth.

NARRATOR: And 66 percent of respondents to a McKinsey survey of executives said that addressing skills gaps among workers was a top ten priority due to technological change.

MARCUS: Right now our tax code sort of supports the investments in capital right and not labor, and so if we could you know put some policies on the books that actually provide firms the incentive to actually invest in labor rather than capital that might actually help as well.

NARRATOR: The future of the American worker is far from written. As automation grows, political solutions could be used to stem the economic pain of a workforce facing an uncertain future.

HICKS: I think the focus was wrong, I mean the focus of the fear of automation should really be a focus on the educational deficits of a portion of our workforce. So we shouldn’t be afraid of automation. It’s going to come whether or not we like it we should embrace it the real public policy challenge is not to stop automation it’s not to be worried about it it’s to be worried about making sure that all of the citizens of the country, all of our workforce, every family has the skills to maneuver effectively in a world that’s more automated or sees more productivity growth which affects labor demand.

LITAN: Both Trump and Obama administrations relied heavily on just having a growing economy absorbing new workers and eventually the tighter the labor market became wages started to go up because employers were bidding for them, and I don’t think that there were a lot of super special efforts to accelerate the transition. I think both administrations rely heavily on just a growing economy in general. I don’t think that’s enough especially in the post-pandemic world. We’re going to need much more affirmative, more active government assistance to get people into new jobs.

ACEMOGLU: There is a notion that has developed over the last several decades that technology is an inevitable path that we’re just following that path, and anything else we try is futile, and I think that’s deeply mistaken and misleading. Technology is what we make it to be. We have a technological problem platform and a knowledge accumulation and we can use these for creating different types of technology automation is just one of them automating everything and making machines produce everything and sidelining humans is just one very peculiar path we don’t have to follow that path that doesn’t mean turning our back on ai doesn’t mean turning our back on digital technologies but it means that looking forward we have to take ownership of the path of technology.