The late Sean Connery was a great movie star, but was he ideally cast as James Bond?

The question that always ran through my mind watching Connery as Bond was “Why is this magnificent Scottish prole playing the quintessential English gentleman?” Especially because there are so many other actors who could play the English gentleman?

These days, British actors tend to come from upscale backgrounds, but back in the time of Connery, Caine, O’Toole and the like, they were more working class.

Bond author Ian Fleming was born to a rich family in the stratospheric London neighborhood of Mayfair. His Scottish grandfather had made the family money in finance, but they were genteel Englishmen by that point.

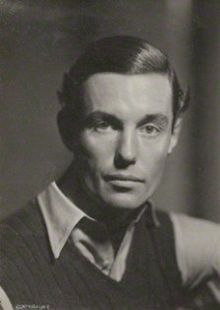

Ian wrote a lot of himself into Bond, but I’d guess that the single best source for his character was his cruelly handsome older brother Peter Fleming, right, a taciturn wit and gifted shooter who was one of the more glamorous travel writers of the 1930s, a field in which numerous wordsmiths such as Waugh and Orwell competed.

Ian wrote a lot of himself into Bond, but I’d guess that the single best source for his character was his cruelly handsome older brother Peter Fleming, right, a taciturn wit and gifted shooter who was one of the more glamorous travel writers of the 1930s, a field in which numerous wordsmiths such as Waugh and Orwell competed.

In a review of Master of Deception: The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming by Alan Ogden, D.J. Taylor writes in The New Criterion:

Fleming’s war travels were every bit as far-flung and hair-raising as his pre-war tours of China. They began with a role in the disastrous Norway campaign of 1940: the dispatches he brought back are thought to have hastened Prime Minister Chamberlain’s resignation. Significantly, Fleming disliked Chamberlain, whom he had met at a house party in the early months of the war, not only for his lackluster military strategy but also for being a feeble shot and not looking the part. (“He is slow and tends to let birds pass before him before he fires. He looks every inch the townsman in his rusty tweeds, handling his gun a trifle gawkishly.”)

Fleming loved wildlife and loved killing it. When his friend King George VI died in 1952, Fleming wrote in his diary, ” “I think he was a very good, but probably not a great, shot.”

Subsequently, he trained a team of guerrilla fighters in Kent with the aim of delaying a possible post-invasion Nazi advance. A visiting dignitary described the hollowed-out badger’s sett beneath the forest floor that made do as an operational base as “pure Boy’s Own Paper stuff.”

Fleming played a major role in setting up Operation Gladio–style saboteur cells in the English countryside in case of German invasion.

There were later missions to mainland Greece, Crete, Cairo, India, Burma, and China. While always happy to risk his neck at moments of crisis—he was lucky to escape when the ship in which he was retreating from Greece suffered a direct hit—Fleming made a speciality of intelligence work, specifically deception: the burned-out jeep with the bundle of forged plans in the front seat designed to frustrate the Japanese advance; the carefully abandoned haversack full of misleading information; the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force member in the Allied Commander Lord Mountbatten’s HQ in Ceylon instructed to write letters about spurious troop movements to a non-existent boyfriend in the hope that they would be steamed open by enemy agents.

After the war Peter passed up the offer of a safe Tory seat in Parliament to be the country squire and shoot partridges.