00:55 The Empires strike back. (UK ructions in historical context.)

14:19 Why do we and the Brits follow parallel trajectories? (Kissing cousins?)

16:36 Chinese love ellipsis. (Baffling for round-eyes.)

22:54 Study 20 Big! (ChiComs hold a congress.)

31:02 Xi Jinping is Party General Secretary. (Don’t call him President.)

35:40 The word salad pandemic. (From China?)

37:59 Japan’s oldest privy takes a hit. (But can still be used.)

39:17 Signoff. (With a light entertainer.)

01 — Intro. And Radio Derb is on the air! Greetings, listeners, from your elliptically genial host John Derbyshire, with news mainly from foreign parts this week. I shall not apologize for that. With the midterm elections just eighteen days away, there will be plenty of domestic news in forthcoming editions of the show.

First, what's all that noise coming from across the pond?

02 — The Empires strike back. Please don't ask me for explanations or predictions on the current situation in British politics. It's not a topic I follow with much diligence. Most of the names being batted around are strangers to me.

I did try to get myself up-to-date by reading the long October 19th Twitter thread by political scientist Daniel Berman. You can read it for yourself at Twitter, or at the handy ThreadReader app. It's a four-minute read, says ThreadReader. Possibly so, but I didn't even make it to the two-minute mark before MEGO. (Sorry: MEGO is tabloid-journalists' slang for "My Eyes Glazed Over.")

Still, although I don't know my Kwarteng from my Sunak or my Shapps from my Mogg, I do believe I understand the large historical context in which to place this undignified scuffle.

The key here is a number. The number is … 2016.

It's a common observation — I've made it myself — that Britain and America travel on parallel tracks politically. In 1979 the Brits got Margaret Thatcher, an economic liberal (in the classical sense) but a social conservative. The following year we Americans got Ronald Reagan, ditto ditto.

Thatcher and Reagan were both followed briefly by pale imitations going through the motions. Then, in the 1990s, both nations elected amoral opportunists — Bill Clinton and Tony Blair — who were mainly interested in enlarging their own net worth.

These whatever-ists ruthlessly offshored their citizens' jobs, relaxed immigration controls — in Blair's case, basically eliminated them — and whizzed around the world attending globalist conferences, striking deals with despots, and smiling for the paparazzi (preferably with winsome-looking black children also in the picture).

Then the first years of the 21st century were, in both Britain and America, given over to futile missionary wars abroad and cultural revolution at home.

It is tempting to see the wars as a smokescreen — a literal smokescreen — behind which the cultural revolution was pushed forward. Britain and America both got legalized homosexual marriage and decarceration of criminals and lunatics. The odious system of Protected Groups was expanded to include the entire Third World so that immigrants — legal or not — from trashcan nations were elevated to social privilege along with native minorities.

The political leadership of those years was characterized by deep mediocrity in both our nations. Did Gordon Brown, David Cameron, and Theresa May really occupy the same office as Margaret Thatcher, Winston Churchill, and David Lloyd George? Or George W. Bush and Barack Obama the same office as Ronald Reagan, Dwight Eisenhower, and Franklin Roosevelt? Hard to believe.

There was, in both nations, a slow-rising public discontent with the cultural overturning and the mass influx of foreigners. The discontent had no significant voice, though. The administrative state was in firm control, the national media its loyal mouthpiece, the education system its seminary, major business corporations its happy auxiliaries, the War on Terror its fallback excuse.

Public expression of that discontent was under strong social disapproval, but the ruling class seemed to be aware of it at some level. British Prime Ministers David Cameron and Theresa May — that is, from 2010 to 2019 — made repeated pledges at election time to cut back on immigration numbers; neither made the slightest effort to do so once in office.

Then, in 2016, the discontent found its voice in both nations. The British Establishment allowed a referendum on Brexit — leaving the European Union. Nobody in the Establishment thought Brexit would pass. Nobody they knew wanted to leave Europe. If any of them had thought the referendum might pass, there would have been no referendum. Brexit passed, though, by 52 to 48 percent.

A few months later that same year outsider Donald Trump won America's presidential election. The popular vote here was even less decisive than it was for Brexit: Trump actually lost it, 46 percent to 48. He won the Electoral College vote, though, so the constitutional requirement was satisfied and he became president.

The Establishments in both nations were traumatized. The consequences here in the U.S.A. are of course familiar to listeners. For the next four years — indeed, in some regards down to the present — our ruling class went through something strongly resembling collective insanity. However, they recovered sufficient of their wits to right the situation in 2020, and they are now firmly back in control.

Here the British situation has been different. Unlike the 2016 American rebellion, Brexit had major impacts on both sovereignty and economics.

The sovereignty issue concerns Northern Ireland, a sovereign part of the United Kingdom. It has of course a land border with the Irish Republic, an independent nation and member of the EU. How to square the circle of combining EU trade rules with a now-independent British trade policy?

My own solution, were I Prime Minister of Britain, would be to do to Northern Ireland what Charles de Gaulle did to Algeria: bye-bye, sorry! This does not seem to have been considered by Britain's rulers.

And then, economics. British independence of the EU has called for a major restructuring of trade relations, most obviously with the EU itself, but also with the rest of the world where Britain could formerly fall back on EU rules.

So, big economic disruptions — much bigger and more disruptive than anything we Americans can blame on Donald Trump.

Yet the British Establishment, like ours, has regrouped to meet the challenge, although it naturally took them longer to do so. And I really should say "is regrouping," not "has regrouped," as the process is not yet complete. The chaos of recent weeks has all been part of the regrouping.

Britain's rulers are most of the way there, though. They have recovered their strong sense of collective identity and a determination not to blunder into any more populist shocks, as David Cameron did with the Brexit referendum.

The immigration issue illustrates their gathering confidence. Liz Truss, the Prime Minister who just resigned after only six weeks on the job, had announced in her first major speech last month that she would greatly expand immigration to stimulate economic growth. That put her at odds with her cabinet colleague Suella Braverman, an outspoken immigration skeptic.

Yes, Liz Truss will soon be gone, but … Suella Braverman is already gone, forced to resign on Tuesday this week over a trifling breach of security.

The real reason for Mrs Braverman's defenestration is of course her heterodoxy on immigration. Britain's ruling class wants to restore the David Cameron / Theresa May / Boris Johnson policy of solemn promises around election time followed, once safely elected, by no action whatsoever.

British commentator Toby Young was wondering on Wednesday at The Daily Skeptic whether the phrase "a globalist coup" is appropriate for what's been happening over there. He left the question mark in place. Like Toby, I'm not sure that "globalist coup" fits the bill precisely, but it's pretty darn close.

Like our own Establishment, British elites loathe and fear their own citizens and dream of replacing them. The 2016 shock disturbed that dream; but now they have recovered their confidence. They are sure that, if they can just get the right bottoms in the right chairs, they can get back to something like what Orwell called "the dear old game of scratch-my-neighbour."

The ruling Establishments on both sides of the Atlantic have deteriorated badly across my lifetime, to the point where they are now reptilian scum. Still, although their mean IQ has plummeted, they maintain a sort of criminal low cunning. Whatever emerges from the current scuffling in Westminster or the November midterms over here, I doubt it will make much difference to the long-term historical trend.

03 — Kissing cousins. Just a footnote to all that.

I started that segment with the oft-noted observation that Britain and America travel on parallel tracks politically. Why is this so?

The two nations could not be more differently situated. America is continental; Britain is a bunch of offshore islands. The areas are in ratio sixteen to one; populations, five to one.

OK, we are cousin nations, with some common heritage and a common language. Does that really have much effect nowadays, though? A lot of water has flowed down the Mississippi since America's population was majority British. Even if you limit the inquiry to Americans of British descent, there's no longer much family resemblance. To a truck driver from Huddersfield, a Mayflower descendant in Boston — or an Appalachian dirt farmer, for that matter — is as alien as a Hottentot.

Our political systems are likewise very different. The joke going round among pundits this week has been that Britain's politics is superior to ours in at least one regard: When their top politician blunders badly, they can get rid of him — actually, of course, in this case her — in a matter of days, without having to wait for a four-year cycle to complete.

So are those parallels just chance occurrences? Or is there something deeper going on? I'm curious to hear listeners' opinions.

When I first visited mainland China, forty years ago this month, I was somewhat baffled to see big posters everywhere bearing the four Chinese characters 学十二大 (xué shí-èr dà). I knew enough Chinese to translate the characters: they meant STUDY TWELVE BIG. I just couldn't figure the meaning. Twelve big what?

Here I'd come up against a very characteristic quality of the Chinese language: It loves ellipsis. For those of you who've forgotten your figures of speech, ellipsis is omission of a word or an entire phrase when you can be sure the listener will understand your meaning anyway.

The proverb, "Everybody's friend is nobody's," uses ellipsis. In perfect grammar the statement should be, "Everybody's friend is nobody's friend." You can omit that second "friend," though. Experienced users of the English language will know that it's meant.

Chinese does that a lot. That last character on those posters that baffled me, the dà in xué shí-èr dà, is an ellipsis. It's an ellipsis for 中国共产党第十二次全国代表大会 (zhōng guó gòng chăn dăng dì shí-èr cì quán guó dài biăo dà huì. It's actually the penultimate syllable there if you listen carefully.

That's one hell of an ellipsis, from fifteen syllables down to one; but that's the Chinese language for you. The last two syllables of the fifteen, dà huì, translate as "big meeting." The two prior syllables, dài biăo, mean "representatives," so this is a big meeting of representatives — a congress. The whole fifteen-syllable deal translates to: "The twelfth national congress of the Chinese Communist Party" — shí-èr dà for short: Twelve Big.

The reason I was seeing posters everywhere telling me to STUDY TWELVE BIG was that the twelfth party congress had happened the month before and the ChiComs wanted their citizens to pay attention to what had been decided.

What had been decided? Well, the big takeaway, the headliner, was that Deng Xiaoping was to be China's supreme leader. Everyone kind of knew that anyway, but Twelve Big made it official.

These grand party congresses occur every five years. That twelfth one was, as I said, in the Fall of 1982. The previous one, Eleven Big, had been held in 1977. The big news from Eleven Big had been the end of the Cultural Revolution — which, again, people kind of knew, but Eleven Big made it official.

Eleven Big also made it official that Hua Guofeng was the supreme leader. Hua is my favorite of all the ChiCom leaders, and the name of the policy he promoted is my favorite of all names of all policies ever promoted by any government anywhere. The official name of the policy was The Two Whatevers.

No kidding, that was the name of his policy: The Two Whatevers. In Chinese: Liăng-gè Fán-shì My only objection to it is, it's a bit spare. If I ever get to be Supreme Leader somewhere, I shall promulgate a much more abundant version — The Seventy-Five Whatevers, perhaps — and I shall make all citizens memorize them.

So … If these ChiCom party congresses are held every five years, and if number twelve was in 1982, that was forty years ago … forty divided by five is eight … twelve plus eight is twenty … we should be due for Twenty Big, right?

That's right. Twenty Big has in fact been going on all week. It started on Sunday the 16th and ends tomorrow, Saturday the 22nd. After it's done they'll be pasting up the posters: STUDY TWENTY BIG!

05 — STUDY TWENTY BIG! Again I have to confess to delinquency here. As VDARE.com's resident China buff I should give you a comprehensive rundown of what has transpired at Twenty Big. I should in fact be hard at work STUDYING TWENTY BIG! for the benefit of you listeners.

Well, I haven't been; but I do have excellent excuses for my delinquency.

For one thing, as I noted when talking about Twelve Big and Eleven Big, you don't learn anything from these congresses that you didn't already kind of know. Nothing astonishing gets revealed at a party congress. That's why the press coverage makes dull reading.

For another thing, as boring as these congresses are to read about, they must be boring on a cosmic scale for those in actual attendance — more than two thousand of the poor devils. Xi Jinping's opening speech on Sunday went on for two hours. And that was the abridged version of a written report whose English translation, runs (or crawls) to 25,000 words — over sixty pages in an average book. There must be a huge spike in sales of NoDoz around central Peking at congress time.

So it's understandable that Western press reports of Twenty Big — which I have been reading fairly diligently — concentrate on the mood and style of what's said, in lieu of any substance.

The Washington Post's report today, Friday, for example, notes an emphasis on security, both at home and abroad. Quote from them:

In a congress report released this week, the word "security" appears 91 times, up from 55 mentions in 2017 and 36 in 2012. Xi's "comprehensive national security concept" — a slogan urging the active detection and management of threats in all areas of policymaking — has its own section for the first time. The "global security initiative" he announced in April was also included. ["Under Xi, China wants absolute security. It's making the world nervous." by Christian Shepherd and Lyric Li; The Washington Post, October 21st 2022.]

End quote.

That brings to mind Peter Thiel's description of China last year as, quote, "a weirdly autistic country," end quote. This obsession with security, with order and control in Xi Jinping's China, and what Thiel, in his next sentence, called that country's "profoundly uncharismatic" affect, really does make one think of a neurological disorder.

This week's edition of The Economist took word-counting to the max. Edited quote from them:

Readers may notice how certain words have been gaining in frequency of use from congress to congress …

One such word is "security." It appears 91 times in the document, compared with 35 in the farewell report delivered by Mr Xi's predecessor Hu Jintao … in 2012 … Another rise has been in uses of the word "military." There were 21 this time. In 1982, at the first congress of the Deng Xiaoping era, there were just four. The word "struggle" appears 22 times in the latest report. Hu Jintao used "struggle" only five times in 2012.

Mr Xi offered no hint of any political relaxation. The term "political structural reform" made a dramatic debut at the congress in 1987, with 12 mentions. This time Mr Xi did not use it, the first such omission since that time. ["In his reports to the party, Xi Jinping signals change subtly"; The Economist, October 20th 2022.]

End quote.

So Xi Jinping is a control freak totally hostile to political reform. Once again: You don't learn anything new from these congresses.

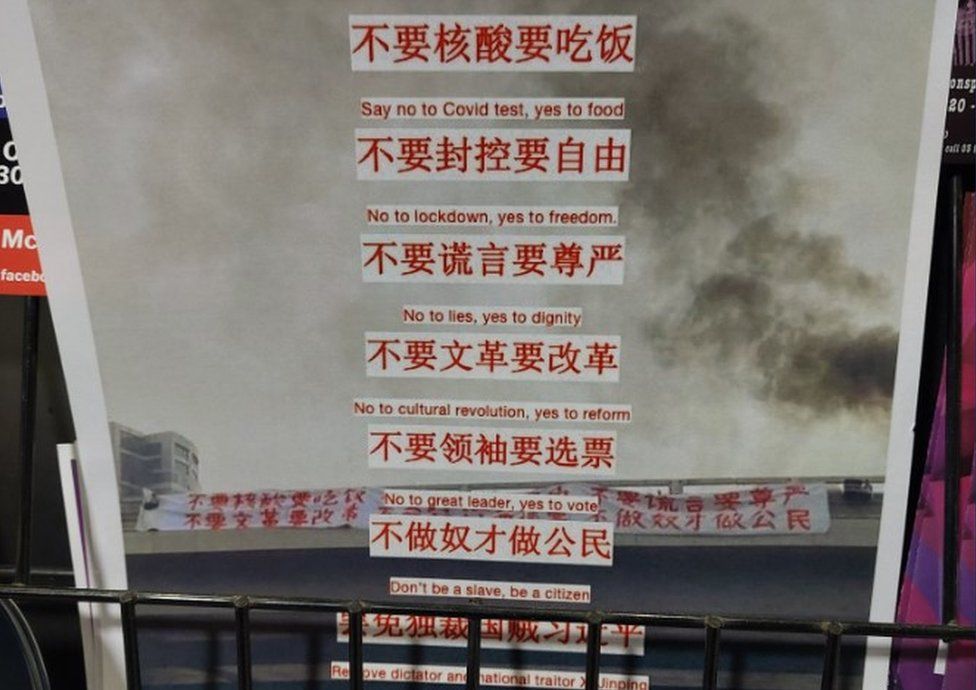

Do Chinese people actually want any political reform? Well, some of them do. Thursday last week, three days before the congress opened, a very brave man draped four large banners from a road bridge in central Peking. The slogans on the banners read thus, quote:

Say no to COVID test, yes to food.

No to lockdown, yes to freedom.

No to lies, yes to dignity.

No to cultural revolution, yes to reform.

No to Great Leader, yes to vote.

Don't be a slave, be a citizen.

Remove dictator and national traitor Xi Jinping.

End quote.

The perp is apparently an academic, a physicist. After hanging out his banners he waited quietly for the police to come and arrest him, which they soon did. His current circumstances don't bear thinking about.

The banners were of course quickly taken down, and the ChiCom authorities got busy scrubbing any mention of the incident from social media. The name of the bridge, and even the word "bridge" itself, have almost vanished from the Chinese internet. Our own FBI is watching all this laundering of language with keen interest …

06 — Miscellany. And now, our closing miscellany of brief items.

Imprimis: You've probably read that Xi Jinping is going to get himself voted President for a third term at Twenty Big, and that this is an innovation.

It sort of is, but it's a very trivial one. The Presidency of China is purely honorary; the President as such has no duties of any importance. China expert Katherine Wilhelm tells us in Wednesday's The Washington Post that Mao Tse-tung gave up the title "because he was bored by the paperwork." From 1969 to 1982 — thirteen years — nobody held the title at all.

Communist China has no real national state structure, only the Communist Party. China's national leader is the General Secretary of the Party — currently of course Xi Jinping. The Party holds all power; state titles outside the Party have no meaning, no power, no authority.

There are no term limits on being the Party General Secretary. You can be General Secretary for life, and it looks as though Xi Jinping is aiming for that.

When China came out of its shell after the Mao years, however, and Chinese leaders had to mingle with their equivalents from other nations, the title of President became handy, so it was written into the 1982 Constitution — which was, incidentally, China's fourth constitution since the commies took over in 1949. The presidency clause was written in with a limit of two consecutive five-year terms.

Still, even with that clause in the 1982 constitution, no-one of any importance served as president until 1993. The title was awarded to faithful Party members who were thought to be deserving of some recognition but no actual responsibility. Then General Secretary Jiang Zemin awarded it to himself, and every general secretary of the party since has also been president.

As part of his plan to be General Secretary for Life, Xi Jinping thought it would be cool if he were also President for Life, so in 2018 he had the constitution amended to remove the term limit on the presidency. This seems to have been just a whim; it didn't change anything that matters.

There is of course no formal nationwide vote on amending the constitution. If the General Secretary of the Party wants it changed, it gets changed.

We shouldn't go along with the fiction that there is any power in China other than the Party's power. As Katherine Wilhelm writes, quote:

When we insist on using Xi's state title while ignoring his party title, we participate in a charade that pretends important decisions in China are made by the apparatus of the state, instead of by the party.

In China's own media, Xi is almost always identified as the party general secretary. Let's follow their example and ditch the word "president." ["It's time to stop calling Xi Jinping the "president" of China" by Katherine Wilhelm; The Washington Post, October 19th 2022.]

End quote.

[Clip of Kamala Harris speaking: Today the business of our work is for the Council to report on the work that has occurred since our last meeting across these areas. We will today also discuss the work yet ahead, the work we must still do to continue to move forward …]

That was of course our nation's Vice President delivering one of those addresses of hers that have made the phrase "word salad" common currency.

It's not just the Veep. There seems to be a pandemic of word salad going round. Here was human sciences pundit Jordan Peterson the other day.

[Clip: Well, the question, "Did that happen?" begs the question: "What do you mean by 'happen'?" Because when you are dealing with fundamental realities and you pose a question, you have to understand that the reality of the concepts of your question when you're digging that deep are just as questionable as what you're questioning, you know? So people say to me, "What do you … do you believe in God?" and I think: "OK, there's a couple of mysteries in that question. What do you mean, 'do'? What do you mean, 'you'? What do you mean, 'believe'? And what do you mean 'God'?" And you say, as the questioner: "Well, we already know what all those things mean, except belief in God." And I think: "No. If we're going to get down to the fundamental brass tacks, we don't really know what any of those things mean …"]

After listening to that, and the Vice President, and taking some random brief dives into Xi Jinping's speech at Twenty Big, I'm going to put forward the hypothesis that a dangerous new virus is on the loose, likely escaped from a Chinese biowarfare facility, causing the speech of otherwise-sane people to degenerate into word salad.

Item: A sad story from Japan this week. That nation's oldest toilet suffered serious damage when a careless driver backed his car into it. Quote from BBC News, October 18th, quote:

The communal loo at Tofukuji in Kyoto dates back to the 15th century and is designated an important cultural asset.

Its ancient door was ruined after the employee hit the gas without realising the car was in reverse, police said.

No one was injured and the actual latrines inside remained intact.

End quote.

That last sentence at least offers some relief. Apparently you can still use the six-hundred-year-old restroom; although, from what I remember of traditional East Asian bathroom facilities, you probably shouldn't look for somewhere you can sit down.

07 — Signoff. That's it, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for your time and attention; and thanks from Mrs Derbyshire to those who emailed in to wish her a happy birthday. It was a happy birthday, with flowers, cards, and a trip to the Oyster Bay street festival.

Signing off last week's podcast I noted in passing that Sunday October 16th was the 100th birthday of Max Bygraves. I can't remember why I thought that worth a mention, and I didn't say anything further about it. Bygraves was a British entertainer of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, who I assumed was completely unknown to Americans.

Not completely, I have learned. Listeners have emailed in to voice their disappointment that, having mentioned Bygraves, I didn't close with one of his songs. Among those listeners were two I know to be entirely American. Reading his Wikipedia entry more attentively, I now see that he was a TV guest on the shows of Ed Sullivan, Jack Benny and Jackie Gleason. People have long memories.

Bygraves was an entertainer, but not a heavyweight one. He had a pleasant singing voice, but he was no Sinatra or Tony Bennett; and the songs he's most remembered for singing were light pieces with easy melodies, not Cole Porter or Irving Berlin. He did a lot of comedy, but I can't remember any of his routines.

That's not to put the guy down. I remember him very fondly, especially from the radio shows of my childhood. Lightweight entertainment is better than no entertainment at all, and way better than the politicized dreck offered by today's late-night comics.

Bygraves added much to the public sum of harmless pleasure, and that's something to thank him for. He passed away ten years ago. I hope he rests in peace.

[Music clip: Max Bygraves, "Tulips from Amsterdam."]

Can't load tweet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qPsq6flck2A: Sorry, that page does not exist