James Fulford writes: With Donald J. Trump fulfilling his campaign promise to do something about China's predatory trading tactics, Free Trade vs. Tariffs has come up again in American politics. I emphasize"again", because as Pat Buchanan wrote in Tariffs—The Taxes That Made America Great, the first time it came up after the American Revolution was when George Washington signed the 1790 Tariff Act. The American Revolution itself was partly a result of Britain's decision to impose tariffs on, for example, tea.

Tariffs also came up in Pat Buchanan's 1996 run for the Presidency, and Peter Brimelow wrote this column explaining it to the readers of the London Times.

Originally published as Patriotic Games, Times of London, February 24, 1996

No one is more horrified than the leaders of the comfortable conservative establishment that has grown up in Washington since Ronald Reagan's first victory in 1980 that a White House speech writer and ex-newspaper columnist called Patrick J.Buchanan is seriously running for President.

No one is more horrified than the leaders of the comfortable conservative establishment that has grown up in Washington since Ronald Reagan's first victory in 1980 that a White House speech writer and ex-newspaper columnist called Patrick J.Buchanan is seriously running for President.

Oddly, they seem to feel no gratitude that Mr. Buchanan loyally allowed himself to be persuaded not to run in 1988 because these same leaders wanted to anoint Congressman Jack Kemp. He turned out to be one of the great duds of recent American political history.

The immediate reason why the Buchanan phenomenon is possible and, despite all assertions to the contrary, why it will quite probably continue to happen, is the extraordinary flexibility of American political institutions. Mr. Buchanan can go directly to the voters. He cannot be contained within a parliamentary system, as Enoch Powell was after 1968. Senators and governors can endorse Bob Dole. But they cannot necessarily deliver.

This flexibility is certainly alarming for professional politicians, and for pundits, who can never be sure whom to fawn upon. But it allows America to change course very quickly, for example from Cold War defeatism under President Carter to victory under President Reagan.

The ultimate reason that Buchanan will continue to happen, however, is more fundamental and something British readers should recognize. Like the British Empire almost a century ago, the American empire is passing through a seachange. As in Britain, most of the political class is too complacent to notice.

But Mr. Buchanan has noticed. Despite his brawling style, he is formidably intelligent and well-read; he also likes cats. In this and other respects, he bears an almost eerie resemblance to the most brilliant figure in turn-of-the-century British politics: the radical Liberal Mayor of Birmingham turned Tory Colonial Secretary and imperial federationist, Joseph Chamberlain.

But Mr. Buchanan has noticed. Despite his brawling style, he is formidably intelligent and well-read; he also likes cats. In this and other respects, he bears an almost eerie resemblance to the most brilliant figure in turn-of-the-century British politics: the radical Liberal Mayor of Birmingham turned Tory Colonial Secretary and imperial federationist, Joseph Chamberlain.

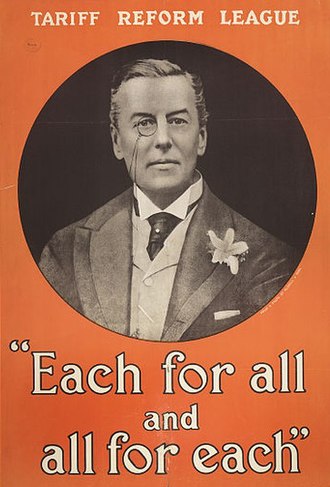

Chamberlain now is much less well remembered than his Prime Minister son, Neville. But he was more significant. Like Mr. Buchanan, he broke with his party's leadership, and a free trade consensus that had hardened into dogma over 50 years, to campaign for a return to protectionism. His extra-parliamentary vehicle was the Tariff Reform League, founded in 1903. But, again like Mr. Buchanan, Chamberlain's support for tariffs was not the result of pure economic theory but part of a carefully thought out and internally consistent strategy a weltpolitik, in the language of one of the protectionist empires that were emerging as Britain's geopolitical rivals. (The other was the United States.)

Like Mr. Buchanan, Chamberlain was at heart a patriot, which is why he had split from Gladstone over Irish Home Rule. He wanted consciously to consolidate the Empire that Britain had acquired in Seeley's famous "fit of absence of mind". He believed that political federation of Britain and the white dominions was a real possibility.

Nowadays, all this has been forgotten. But at the time, it was taken very seriously. On the face of it, it was surely no more improbable than the European Union. And if there was nothing to it, why did my father share a trench in Tobruk with Australians and South Africans and come home to Lancashire to find his sister had been carried off by a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force?

Nowadays, all this has been forgotten. But at the time, it was taken very seriously. On the face of it, it was surely no more improbable than the European Union. And if there was nothing to it, why did my father share a trench in Tobruk with Australians and South Africans and come home to Lancashire to find his sister had been carried off by a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force?

Chamberlain saw tariffs as a way of causing trade to underpin this political federation. Imperial preference was also a bargaining chip to offer protectionist-inclined dominions, such as Canada. And Chamberlain saw tariffs as a way of financing social services, the implicit bargain he offered the British workers to compensate them for dearer food.

The American empire, of course, no longer has geopolitical rivals. Unnoticed, however, Mr. Buchanan also sees trade as a diplomatic weapon: his attacks on the North American Free Trade Agreement exempt Canada, which he regards as culturally and economically compatible in a way that Mexico, with its Third World wage levels, is not.

The threat to the American empire is internal. Whatever the benefits of more free trade as a whole actually quite marginal at these levels it does redistribute income from specific groups in particular. Since the 1970s, real wages have arguably stagnated for the American working class. They do not like it.

This is the group that is suffering most from two other policies that Mr. Buchanan attacks, to the embarrassment of Washington conservatives: Affirmative Action and immigration. Affirmative Action—code for racial quotas in employment— has put politics in command of large parts of the American economy without a peep from those economists who are scandalized by the thought of tariffs, although these are just another form of tax. Immigrants, predominantly from the Third World, who are immediately eligible for affirmative action quotas, are at record levels.

The 1990 census revealed an astonishing net migration of Americans from states such as Florida and California which have attracted large numbers of immigrants. It is conceivable that these areas will be wholly foreign in a few years.

But not if America's flexible institutions, and Pat Buchanan, can help it.

Peter Brimelow [Email him] is the editor of VDARE.com. His best-selling book, Alien Nation: Common Sense About America’s Immigration Disaster, is now available in Kindle format.