The Cerulean Decade? The 1890s is known as the Mauve Decade. I don’t know why it took so long for mauve to sweep the world of fashion; a fabric dye for the color was actually discovered (invented?) in the 1850s. These are the mysteries of sociology.

I’m developing a theory that this decade, the 2020s, may be the Cerulean Decade. I haven’t gotten very far with the development yet, so I’ll give you the theory half-baked.

Color me confused. If you say the word “cerulean“ in company, everyone starts reminiscing gleefully about that scene in The Devil Wears Prada when Meryl Streep humiliates Anne Hathaway for the color of her sweater.

Hathaway, says Streep, fondly imagined she was exercising an inspired act of autonomous free choice when she bought the sweater; in fact, the choice had been made for her years before by the fashion industry. Cerulean, ha!

It’s a great scene, but … what exactly is cerulean?

There seems to be a lot of latitude in the definition, at least as given by my 1993 edition of Webster’s Third.

cerulean adj 1 : somewhat resembling the blue of the sky 2 : of the color sky blue

But then

cerulean n the color of the sky on a bright cloudless day : deep blue or azure

And then

cerulean blue n 1 a : a variable color averaging a strong greenish blue that is bluer and duller than grotto or cobalt blue and bluer and lighter than indigo carmine b : a strong blue that is greener and stronger than Sèvres and greener, lighter, and stronger than Victoria blue—called also coelin 2 : a stable light greenish blue pigment consisting essentially of oxides of cobalt and tin and used as an artist’s color

Now I’m thoroughly confused. Who knew there was so much to be said about a color? Well, I bet that Meryl Streep character (said to be based on Vogue editrix Anna Wintour) knew. I didn’t, though, and I’m not keen to learn. In what follows I’ll use “cerulean“ to mean any lightish shade of blue that thrusts itself on my attention.

Chromatic creep. It started this spring in my morning walk of Basil, the Hound of the Derbyshires. One of my neighbors, I noticed, had redecorated the front of his house. The shutters and the front door were now all cerulean. Looks nice I thought. Basil passed comment in his own doggish way, although fortunately in the gutter, not on my neighbor’s lawn. We walked on.

A few weeks later I saw that another neighbor, a few houses further along, had repainted his front door … cerulean. And then, somewhat later, another.

What was up with all this cerulean? Even the local utility firms seem to be in on the act, to judge by their road markings.

Not even my own domestic interior is safe, I learned. As designated dishwasher for the Derbyshire family I have for years—decades!—been a user of Scotch-Brite heavy-duty green-and-yellow scouring pads. Then, passing through the kitchen on my way to the refrigerator one day in mid-July, I happened to glance into the sink. Eeek!

Does cerulean have the staying power to get a whole decade named after it? As I write, 35.6 percent of the way through the 2020s, I wouldn’t venture a prediction. Perhaps we could ask Anna Wintour … or Elon Musk.

Bye-bye cerulean birdie. A big push factor in the rise of cerulean has surely been Twitter.

That little cerulean bird logo attained its present familiar form in 2012. There are depths of meaning in it that I wasn’t aware of until ten minutes ago, along with some neat geometry.

That little cerulean bird logo attained its present familiar form in 2012. There are depths of meaning in it that I wasn’t aware of until ten minutes ago, along with some neat geometry.

The shape is much more circular than a real bird—in fact, the design was formed by 15 circles superimposed in layers on top of each other, creating perfect curves in the beak, head, wings and chest. The bird is looking upwards, to represent hope, freedom and development, while the circles used to create it are said to represent connecting people and ideas.

That’s a lot of American idealism packed into one logo.

The Twitter bird has certainly penetrated our national consciousness. Drudge Report recently front-paged a story about the Zuckerberg-Musk feud in cerulean type.

However, as you have been hearing this last week of July, that little Twitter bird, that cute little cerulean symbol packed with idealism, will shortly be hanging in Elon Musk’s game larder. Musk is replacing it as logo with a crude uppercase white-on-black “X“.

Will Musk’s rebranding slow, perhaps stop, possibly even reverse the advance of cerulean? I won’t venture to speculate.

The rebranding may itself be reversed. It’s been meeting resistance from Twitter users and has been widely pooh-poohed by people who know way more than you and I do about this stuff.

Marketing experts said that the move was an unnecessary gamble on a hazy future, coming from a platform with wide brand recognition. Though Twitter has weathered a year’s worth of bad news—its ad revenue is down 50 percent, alternatives are springing up, and regulators are circling—they said it would not make sense for the company to dodge by changing its handle…

“For most users and advertisers and folk in the tech world, the product itself is the problem,“ said Boston College communications professor and branding expert Michael Serazio. “Putting a new name on it doesn’t change that in any material way.“

Furthermore, there are difficulties in registering a letter of the alphabet as your company’s trademark.

In the world of trademarks, the letter “X“ is far from unclaimed territory. In fact, it is so extensively used and cited that it could become a hotbed for legal disputes. “There’s a 100% chance that Twitter is going to get sued over this by somebody,“ trademark attorney Josh Gerben told Reuters. He further revealed that there are “nearly 900 active U.S. trademark registrations that already cover the letter X in a wide range of industries.“

Architecture in black and white. All that said, it is just possible that Elon Musk is ahead of the style trend with his new black and white logo. It may be—I hope it’s not, but it could be—that the 2020s will be remembered not as the Cerulean Decade but as the Black and White Decade.

In support of that possibility here is another house in my middle-middle-class suburban neighborhood, and here’s yet another. Both are recent refurbishments.

Possibly this is just a Long Island thing. Are sales of colored—other than black and white—exterior paint and siding slipping downwards nationwide? Someone must know.

How do I feel about this style? I hate it. It looks … I dunno … defiantly anti-human somehow, like Musk’s new logo. Color me cerulean.

Movie moments. Apropos that Meryl Streep monologue in The Devil Wears Prada: Ms. Streep is also on my list of favorite movie one-liners for “May I have the car keys?“ after smacking Jack Nicholson in the face with a key-lime pie in Heartburn.

It’s a short list; I don’t have good movie memory. If I sweated it I could probably come up with a dozen, but all I can offer just now are:

Sean Connery to Jill St. John in Diamonds Are Forever: “Providing the collars and cuffs match.“https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=40&v=tDSa2uoqxL0&feature=youtu.be

James Mason to Edward Fox in The Shooting Party: “You weren’t shooting like a gentleman, Gilbert.“

07—Is love dead? I spotted this sad little note from a teacher of literature on Twitter the other day.

Teaching Romeo and Juliet for a while now, and the most disturbing emergence and generational shift in the last handful of years is that kids no longer believe in love.

This is a catastrophic development.

Just underneath this is the inability for faith itself.

I think I know what he means. My son and daughter are both Millennials, ages 28 and 30. They are normal—physically and mentally healthy, thank God, smart and sociable, better-than-average looking. Neither, however, so far as I can tell, is the least bit romantic.

Has either of them ever felt the tender passion? If so, I saw no outward sign of it, and I don’t know a properly parental way to ask. At their ages I had been deeply in love two or three times, and I think the same is true of most of my generation.

All right, sample of two. I have other data points, though. The recent death of Tony Bennett reminded me of a conversation I had with a non-Derbyshire millennial two or three years ago. I had praised the Great American Songbook, of which I’ve been a devotee all my life. The other party replied with a sneer (well, I may have imagined the sneer) that those old lounge-singer numbers were “sappy.“

And then there’s this teacher of literature, who has close contact with way more of the post-boomer generations than I have. One commenter posted in the tweet’s comment thread that:

Romantic love is a unique European cultural creation, a spiritual elevation of the passion for sex and reproduction into a foundational institution of civilization. It depended on a certain understanding of the proper relation between man and woman, which is no longer taught.

That commenter’s first assertion is just false. There is nothing uniquely European about romantic love. Chinese people were writing love poetry way before China’s engagement with Europeans—more than two thousand years before in the case of some poems.

Love is a human universal, and has always been present. What I was feeling for my teenage crushes, and feel today for Mrs. Derbyshire, is the same thing Jacob felt for Rachel, Pyramus for Thisbe, and Liáng Shānbó for Zhù Yīngtái.

If this be error and upon me prov’d, I never writ, nor no man ever lov’d.

That commenter’s second sentence is not so compehensively wrong, but it needs some qualification. Our commenter seems to be channeling whichever Frenchman it was who said that: “Nobody would ever fall in love if he hadn’t read about it first.“

Nonsense. Love is part of human nature. Like other components of our nature, it may be encouraged or stifled, but it doesn’t need to be “taught.“ If that first tweeter is correct, romantic love is being stifled among the younger generations. How? Why?

Ideology may be the reason. It may be that angry ideologies like Wokeism, and the sternly puritanical style of religious belief that is close kin to ideology, draw somehow on the same deep mental resources as romantic love. If that’s the case, it’s difficult for passionate adoration of another person to coexist in the same psyche with the desire to burn witches.

Perhaps that is why the stricter kind of totalitarian government always targets romantic love. The Khmer Rouge believed it to be a loathsome bourgeois aberration and shot people who displayed love’s symptoms.

Totalitarians hate human nature. “In class society there is only human nature of a class character; there is no human nature above classes,“ declared Mao Tse-tung. There are only “social constructs“ forced up us by our enemies—capitalists, foreigners, white supremacists, the Jews.

That’s pretty much the mentality we have sunk into this past thirty years. Is it any wonder that romantic love is out of fashion?

Handgun saga: the conclusion. The long saga of my encounter with New York State’s Red Flag law reached a final sweet conclusion this month. Yes, I bought myself a handgun.

It’s nothing glamorous, just a second-hand Colt .38 detective special, fourth issue.

The main thing I had in mind was to get to work depleting the stock of .38 ammo that’s been sitting on a shelf in my attic this past 4¼ years.

I’m enjoying the feeling of completion, though; and of course the knowledge that if civilization were to collapse next month, at least I and my family wouldn’t be confronting barbarism totally defenseless.

Fiction of the month. Writing about our expedition to Texas in my April Diary, I recorded my discovery (well, I must have known about it, but not in any depth up to then) of the western frontier’s child captives—white American  children, that is, captured and raised by Indians.

children, that is, captured and raised by Indians.

I registered my surprise at learning that:

The ones longest in captivity were the most reluctant to return to the white world. When they were forced to, as the tribes were hustled off into reservations in the 1870s, they were usually miserable. (Neither of the females, by the way, recorded anything but kindness from their Indian captors.)

The two females in that parenthesis were among just nine children covered in Scott Zesch’s book The Captured. They were aged eight and ten at capture. For the fate of an older female, stay with me.

Several readers emailed in to recommend books, both fiction and nonfiction, about the child captives. After some light research I purchased and read Lucia St. Clair Robson’s 1982 novel Ride the Wind, an account, based closely on known facts, of the life of Cynthia Ann Parker.

Parker was kidnapped by Comanche raiders at the taking of Parker’s fort in 1836, when she was eight or nine years old. She grew up among the Comanches, learned their language and ways, and married a dashing young brave named Wanderer. She lived as a Comanche for 24 years before being forcibly returned to her family. She died after a further eleven years of deep unhappiness and inability to adapt to the white world.

I suppose the author has taken some liberties with the facts. (The novel makes much of Parker being blonde, but in all the photographs her hair is black.) Novelists have a license to do that. It makes a good story, though, and sets to you pondering the question I posed in the April Diary: Is civilization better than barbarism?

I come down on the side of civilization, as I did in April. Lucia Robson, while giving a sympathetic account of Cynthia Ann Parker and the Comanches she lived among, doesn’t spare us the horrors of barbarism.

For example: she tells the story of Parker’s cousin Rachel Plummer, captured by Comanches at the same time as Parker, but unfortunately too old—she was seventeen—to be eligible for happy absorption into Comanche life. Instead they made her a slave. You can read Rachel’s story at Wikipedia, if you have the stomach for it.

All that said, there is deep melancholy in the story of a people with an established way of life—territories, folkways, customs, traditions, lifestyles—having it all taken from them by hordes of incoming aliens and being corraled into drab reservations to drink themselves to death.

Sure, the pioneers committed some horrors, too. Ms. Robson doesn’t spare us that, either. The settlement of the West is not a pretty story from either side. I think George Macdonald Fraser captured it well in Flashman and the Redskins. Harry Flashman speaking:

When selfish frightened men—in other words, any men, red or white, civilised or savage—come face to face in the middle of a wilderness that both of ’em want, the Lord alone knows why, then war breaks out, and the weaker goes under …

Usually I just sit and sneer when the know-alls start prating on behalf of the poor oppressed heathen, sticking a barb in ’em as opportunity serves … I know the heathen, and their oppressors, pretty well, you see, and the folly of sitting smug in judgement years after, stuffed with piety and ignorance and book-learned bias. Humanity is beastly and stupid, aye, and helpless, and there’s an end to it. And that’s as true for Crazy Horse as it was for Custer—and they’re both long gone, thank God.

Depths of pettiness. This is really petty but I want to get it off my chest.

I had the annual check-up with our family doctor a few weeks ago. I left his office with the usual list of specialist appointments—urologist, cardiologist, dermatologist, … based on the numbers I’d generated in various routine tests.

So now I’m plodding through that list. I make an appointment with the ologist, show up at his office, check in at the desk, sit and wait in the waiting room to be called, along with a scattering of other patients.

In the fulness of time a young woman appears at the door to the inner sanctum and calls out: “John?“

I guess the idea is to suggest cheerful informality. Not infrequently, however, there are two or more Johns in the waiting room. The effect on them—us—is annoying. Which John is being summoned?

What is so difficult about calling out the entire name? Why is this almost never done? Have these people really arrived at adulthood not knowing that “John“ is a very common name for members of the male sex?

Cheerful informality? In a doctor’s office I would actually prefer stiff professionalism.

There: It’s off my chest.

Moved by Voov. We’ve all heard of the conference app Zoom by now, but until this month I’d never heard of Voov.

I was introduced to it by my wife’s graduating class, a class I taught in China 1982-3. July 9th was the fortieth anniversary of their graduation ceremony; a dozen or so of them wanted to do an online conference-chat to commemorate the event. Voov was the app they used.

I was introduced to it by my wife’s graduating class, a class I taught in China 1982-3. July 9th was the fortieth anniversary of their graduation ceremony; a dozen or so of them wanted to do an online conference-chat to commemorate the event. Voov was the app they used.

I see here that Voov is the international version of Tencent Meeting, a Chinese app. I guess that’s why Mrs. Derbyshire’s classmates chose it, although a good proportion of them now live in the U.S.A. and Canada. I further guess it’s a good reason to keep Voov at arm’s length, if you’re thinking of trying it out.

The classmates are now mostly sixty-something retirees. It was fun to see them chattering away onscreen after so many years. Also embarrassing, as I couldn’t remember the English names I’d awarded them at the start of my engagement, having no confidence in my ability to retain dozens of Chinese names in my head. (I had other classes, too.)

And I felt a bit ashamed. Chinese people are very good at keeping up these lifelong friendships. The classmates chat with each other on social media all the time. I haven’t kept up acquaintances like that; I don’t think many Westerners do.

I spent three years in my math class at University College, London sixty years ago, yet now I remember only two of my classmates’ names. I haven’t seen either since the 1980s, nor engaged with them on social media.

Is it just me? I hope not. I prefer to think it’s cultural; we Anglos just aren’t sociable in the way Chinese people are, across decades without any personal meeting. Watching that happy chatter on the July 9th Voov call, I think the difference (if there is a difference) is our loss.

Change of the wind in China. Speaking of Chinese social media, Mrs. Derbyshire had something curious to report mid-July.

She is a devotee of WeChat, the main Chinese messaging/social-media app. There is, she tells me, a facility within WeChat for downloading and listening to audiobooks.

She particularly favors Chinese translations of Western authors—she knows way more of Ernest Hemingway’s work than I do, having listened to it all in Chinese.

She particularly favors Chinese translations of Western authors—she knows way more of Ernest Hemingway’s work than I do, having listened to it all in Chinese.

Digging back into Eng. Lit., she was listening to Pride and Prejudice in a Chinese translation (Àomàn yŭ Piānjiàn) … until one day she wasn’t. The whole audiobook had been dropped from WeChat, along with a mass of other Western literature.

I suppose there might have been some commercial reason for that; but my lady thinks it’s more likely a sign of the wind changing direction, as they say: China’s cultural wind turning more anti-Western.

Perhaps things will go all the way back to when I was teaching Eng. Lit. there. I got a published article out of the experience. In it I noted that the standard college textbook for the subject was A Short History of English Literature by someone called Liú Bĭngshàn. I observed that:

Mr Liú shows his colours right away, in the preface. “Efforts have been made to apply the basic views of Marxism,“ he declares. He’s not kidding. Engels is quoted four times in the first five pages. On page 17 Stalin is quoted. The relevance of the opinions of German businessmen and Russian despots to the study of English Literature is nowhere explained.

I still have my copy of Mr Liú’s Short History; so if you want to know the orthodox early-1980s ChiCom line (which will perhaps also be the late-2020s line) on Thomas More, Charlotte Brontë, or Thomas Hardy, drop me an email.

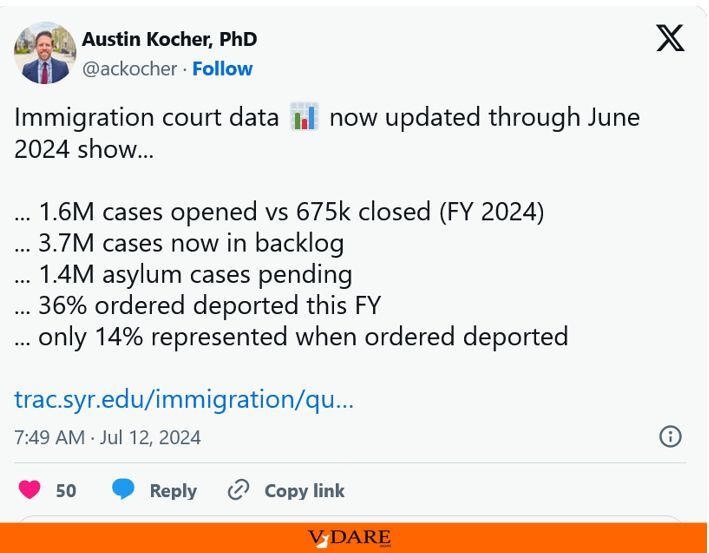

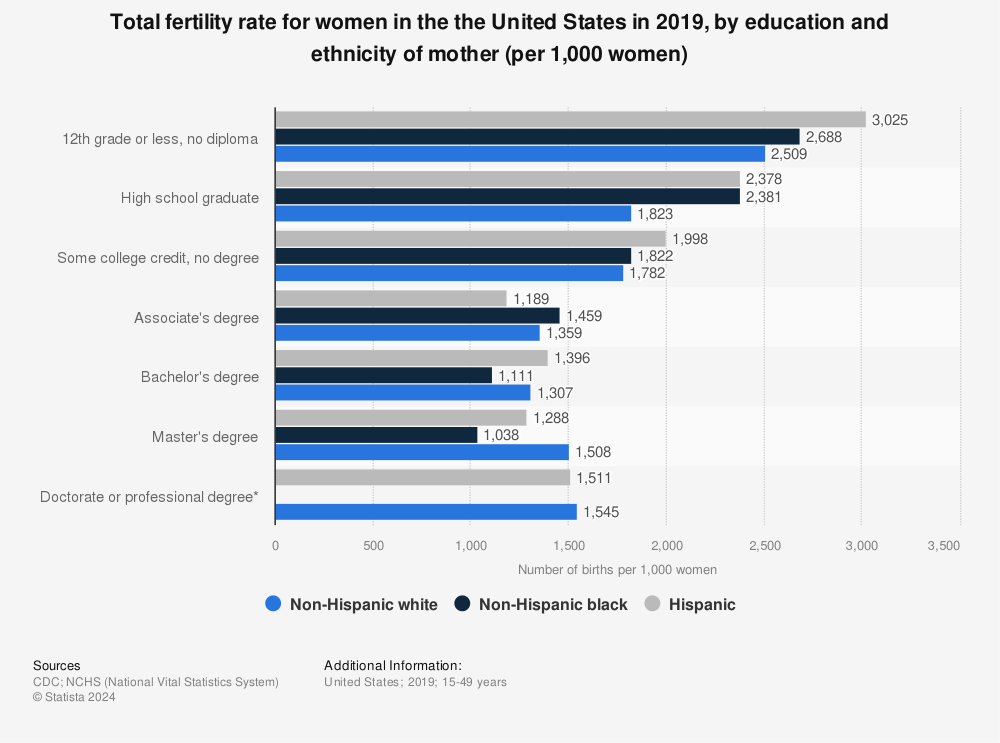

Race, education, and fertility. A friend tells me that the bell curves for IQ are drifting leftwards … but at different speeds for whites and blacks.

He deduces this from a bar chart posted at statistica.com, which is a website for statisticians. The bars on the chart show total fertility rate in 2019 for women in the U.S.A. aged 15-49, broken out “by education and ethnicity of mother.“

A couple of points before proceeding.

- “Ethnicity“ includes race. There are three categories: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic.

- The references to “mothers“ are to the females 15-49 years old generating the fertility stats, i.e., the ones having the babies, not to the mothers of those females. This is normal usage in fertility studies but it’s confusing if you’re not used to it.

- The mother’s education is broken out as seven ascending categories, from “12th grade or less, no diploma“ to “doctorate or professional degree.“

- In that last, highest category there is no bar for non-Hispanic blacks. The reason given is that the figure submitted “did not meet NCHS standards of reliability.“ They don’t tell us why it didn’t.

Bottom line: At the high-school dropout level, blacks lead whites in fertility, 2.688 children per woman v. 2.509. On the other end of the mother’s-education scale, master’s degree, whites are way ahead of blacks: 1.508 v. 1.308. The crossover point is somewhere between associate’s degree and bachelor’s degree.

To put it somewhat crudely: dumb blacks have more kids than dumb whites, but smart blacks have fewer kids than smart whites.

Obviously educational attainment is well correlated with IQ. It’s also well established that American IQ scores have been declining for at least a decade: the Reverse Flynn Effect or Woodley Effect. It is equally well established that educational attainment is to some degree heritable, indeed genetic.

So (my friend argues) if the daughters of black high-school dropouts are having more children than their white equivalents, while the daughters of black and white masters-degree holders are vice versa, the black IQ bell curve must be drifting leftwards faster than the white one.

Sounds reasonable. If it’s true, the coming Idiocracy will be even more race-stratified than today’s U.S.A.

Eh, perhaps AI will rescue us … somehow.

Mysteries of oriental phonology. I know next to nothing about the Korean language, have never even engaged with its alphabet, the Hangul.

Our church, though, has for some years had a Korean gent as its musical director. He’s been in the U.S.A. many years, but still speaks with a strong accent.

July 30th he left us, moving to New York City. Sorry to see him go, we all gave him good-luck cards and small parting gifts. My gift was a book: the Korean translation of Prime Obsession.

The book’s dust cover has the title in big Hangul characters, with below it a string of much smaller characters which presumably say “by John Derbyshire,“ but of course transcribed in Hangul.

On an impulse I asked him to read out that string so that I could hear what my name sounds like in Korean. (In Chinese, as I found out when teaching there in 1982, Tennyson is pronounced “Dingnisheng“ and Shakespeare “Shasibiya“.) Squinting at the characters, he read out in what sounded like perfectly enunciated upper-middle-class British English: “John Derbyshire.“

So it’s as I’ve long suspected: Koreans are one of the ten lost tribes of Anglo-Saxon Britain.

Math Corner. Dr. Peter Winkler at the National Museum of Mathematics concluded his series of “Mind-Benders for the Quarantined“ two years ago as the COVID panic faded away. This was his last puzzle, and it’s a rather neat one.

Brainteaser: Subtracting Around the Corner.

Write down four integers between 0 and 100, in a horizontal line. Now perform the following operation: Compute the (absolute) difference between the first and second, and write it under the first; then write the difference between the second and third under the second; then the difference between the third and the fourth, under the third; finally, the difference between the fourth and the first, under the fourth. You now have a new line of four integers, still between 0 and 100.

Example: If you start with 41 22 6 93, your new line will be 19 16 87 52.

If you repeat this operation you will eventually reach 0 0 0 0. (Why? Note that with five numbers instead of four, this might never happen.) Your score is the number of operations it takes to reach this sorry state.

For the example above, you end up with

41 22 6 93

19 16 87 52

3 71 35 33

68 36 2 30

32 34 28 38

2 6 10 6

4 4 4 4

0 0 0 0

for a score of 7 (pretty crummy).

What’s the highest score you can achieve?

When selfish frightened men—in other words, any men, red or white, civilised or savage—come face to face in the middle of a wilderness that both of ’em want, the Lord alone knows why, then war breaks out, and the weaker goes under …

When selfish frightened men—in other words, any men, red or white, civilised or savage—come face to face in the middle of a wilderness that both of ’em want, the Lord alone knows why, then war breaks out, and the weaker goes under …