2020s China = 1950s America? I spent most of September in China, so last month's diary was all China, China, China. This month's won't be; but I do have a few afterthoughts to record.

A few days after I returned, just when I thought I'd gotten China out of my system and was ready to concentrate on America and her manifold problems, I read a very striking essay at the poli-sci website Palladium.

The essay is longish—nearly four thousand words—but with an exceptionally high ratio of insights to text. The author is Jean Fan, a young American psychologist of Chinese ancestry. She can be seen giving a TEDx talk (not about China) here.

I came at the essay loaded with skepticism, mainly on account of its title: The American Dream is Alive in China. Yeah, yeah, I thought: another puff piece from the ChiCom propaganda office. The internet's full of those. The genre is pinned at its most risible end by the contributions of "Godfree Roberts" at Unz Review.

Titles are thought up by editors, though. An author, unless he swings a lot of weight, should not be blamed for the titles stuck on his journalism. As I read on into Ms. Fan's piece I found myself more and more nodding along in agreement with her observations.

"I grew up in America, but I go to China every year for a few weeks to visit family," she tells us. Her essay is formed from reflections on her last visit, in March 2018.

China has, Ms. Fan tells us, turned some kind of a corner.

Ten years ago, it was obvious that if you could immigrate to the U.S., you should. That mentality has shifted. One of my cousins characterized the new status quo. When I asked her whether she would consider moving to the U.S., she responded: "Why would I? Life is great here." She's not the only one; 20 years ago, almost all Chinese students studying at American universities would stay in the U.S. Now, they almost all go home.

I caught the same vibe, visiting China last month. There's a widespread cheerful optimism, an élan, a general satisfaction with things as they are, along with a belief that they'll keep getting better. National-morale-wise, it's like 1950s America over there.

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, I had always imagined myself living and working here …

But for the first time last March, I found myself thinking: "I might not mind living in China." After all, Chinese cities continue to become cleaner and nicer, people's lives become easier and more convenient, and the government competently handles more and more pressing problems.

Meanwhile, San Francisco's government continues to struggle with worsening homelessness and public disorder. In addition, as I write this piece, millions of people in the Bay are experiencing a multi-day planned blackout. As you might expect, no one is happy about this. My current expectation is that as time goes on, this contrast between the U.S. and China will become more stark. I've since reflected on the idea of living in China. I think that these days, if you're a normal person living a normal life, or even an ambitious entrepreneur, China is a good place to be. Cities are clean and convenient. Life is exciting and fast-paced. Opportunities are plentiful.

Ms Fan is not a shill or a fool. She is clear-headed about the negatives.

I do feel more comfortable navigating the relative disorder and freedom of the U.S. than being in a context where I might quickly need to come to the government-mandated answer.

She has, though, noticed something important about China that has been too little remarked on. I got an inkling of it myself last month. That's why I responded so strongly to this essay. I had been out of China for eighteen years, though. Ms Fan, with her annual visits, has a much better feel for continuities and corners.

The common perceptions of other countries that we carry around in our heads are generally out of date. With today's ease of travel and communication they are no longer decades out of date, as they used to be, but we are still slow to catch on when a nation turns a sharp corner, as China has recently done.

Many of the assumptions Americans make about China are pre-corner, drawn from things as they were five or ten years ago. Many of the things we think we know have ceased to be, or are rapidly ceasing to be, true.

Chinese students in our colleges desperate to get a green card so they can settle here post-graduation? No: As Ms Fan points out, more and more prefer to go home. Wealthy Chinese buying property in the West for security in case China collapses? Not really a thing any more. People still buy for investment, but they're not thinking of bolt-holes. Horrible urban air pollution? I visited five major cities and three small towns last month—north, south, east, and west: The air was fine.

(That last observation needs some discounting for the fact that I was there in September, when the heating of homes and offices is not an issue. A relative from Zhengzhou told me air pollution is bad there, and really bad in winter.)

The last word, from Jean Fan:

In the U.S., we face an ongoing crisis of governance. We need to understand our own failures, and we need to grapple with unexpected demonstrations of success—even if they come from non-liberal societies.

China's success challenges our implicit ideology and deep-seated assumptions about governance. It needs to be studied—not just to bring about better coordination, but because in its accomplishments, we may find important truths needed to bring about American revitalization.

No bottom, no facts. The negatives, yes. Jasper Becker, in his book about the great Mao famine of 1959-61, tells us of a reporter in China in the 1920s responding to a request from his editor for "the bottom facts." Replied that reporter: "There is no bottom in China, and no facts."

That caution is always worth bearing in mind. China's a very big, very old country, with a colossal population. The edges are, as an Old China Hand of my acquaintance used to say, a long way from the middle.

That caution is always worth bearing in mind. China's a very big, very old country, with a colossal population. The edges are, as an Old China Hand of my acquaintance used to say, a long way from the middle.

My time in China last month was spent in cities or substantial towns, among middle-class professional types. These are China's current winners. They are upbeat and doing well. I'm guessing the same applies to Jean Fan's contacts.

What about China's losers? The country's wealth is distributed very unequally. There are a great many poor people living hard lives. I sometimes glimpsed them from the window of a train, but I don't know any of them personally. The ChiComs have had an official War on Poverty for some years, but it seems to be ill-managed, under-funded, and ineffectual.

I'm skeptical about direly negative predictions for China's economy, having reviewed Gordon Chang's book The Coming Collapse of China … eighteen years ago. Professional economists are likewise wary of talking about collapse, but they are none the less bearish: Christopher Balding, for example, quote:

There are very large systemic problems with the Chinese economy, and they're just not dealing with them.

Balding thinks the ChiComs will avoid collapse and preserve their own power by closing China off from the world, becoming "North Korea with a higher level of income."

And then there are the things unseen and unknown. Behind all those staged presentations of unanimity at the top, Chinese politics is probably just as it always has been: a cauldron of intrigue, ambitious factions stalking each other through the corridors of power with daggers drawn.

Not totally unseen but seriously under-reported in the West are China's networks of organized crime. The 39 Vietnamese who perished in a refrigerated truck while being smuggled into Britain last week seem to have travelled via China, where "snakehead" criminal gangs provided them with false Chinese passports.

The crime gangs are everywhere. Entrepreneurs are plagued by them. A Hong Kong acquaintance of mine owned a small business with a workshop in mainland China. He lost his business to the crime gangs, and fears for his life. The law-enforcement and judicial authorities are all bought and paid for by the gangs, he claims.

Other small capitalists are more proactive.

Businessman Tan Youhui hired a hitman to "take out" his competitor for $282,000 … a court heard.

But the hitman hired another man to do the job, offering $141,000. That man hired another hitman, who hired another hitman, who hired another hitman.

The plan crumbled when the final hitman met the man, named only as Wei, in a cafe and proposed faking his death.

All six men—the five hitmen and Tan—were convicted of attempted murder by the court in Nanning, Guangxi, following a trial that lasted three years. [Hesitant hitmen jailed over botched assassination in China; BBC News, October 22nd 2019.]

China footnotes. Just a couple of footnotes to round out the China coverage.

First, some vlogs. Up above there somewhere I had a link to Chris Chappell's China Uncensored, which has been airing on YouTube since 2014. Chris is smart, funny, and unsparing in exposing ChiCom lies and follies. There's some heavyweight political and economic analysis in there, too.

Of more lightweight vloggers who have, at least some of the time (the quality is very variable), interesting things to say about China at the everyday level, the longest-established seems to be Winston Sterzel, a South African fellow who's been vlogging as Serpentza since 2007. Close behind him, and a bit lighter in tone, is Matthew Tye, an American vlogging as laowhy86 since about 2012 (these start dates can be hard to pin down).

Second, perhaps supporting Christopher Balding's speculation about China becoming just a more prosperous copy of North Korea, dubious arrests of foreigners over there seem to be happening more frequently.

In January, the State Department issued a travel advisory for China, warning Americans, particularly those with dual Chinese-American citizenship, that they may be prevented from leaving China if they go there.

The large network of English teachers in China, long a mainstay of the expatriate scene, appears to have come under particular scrutiny. [China Detains 2 Americans Amid Growing Scrutiny of Foreigners, by Amy Qin; New York Times, October 17th, 2019.]

Perhaps I was lucky to have done my own teaching gig back in the early 1980s when things were looser.

Third and finally, a sarcastic email from a reader of my September Diary asking me where Peking is. "I can't find it in my atlas …"

Glad to help out, Sir. Peking is in north-central China; 400 miles southwest of Mukden, 280 miles west of Port Arthur, 1,200 miles north of Amoy. You're welcome!

Nonlinear change. If China's turned a corner in the past not-very-many years, so has America, at least politically.

Razib Khan notes that the 2012 political candidates, Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, look kind of quaint and old-fashioned. Neither of them would stand a chance of nomination by their parties today.

As Razib says:

Cultural change is often nonlinear. Shocks can change the equilibrium.

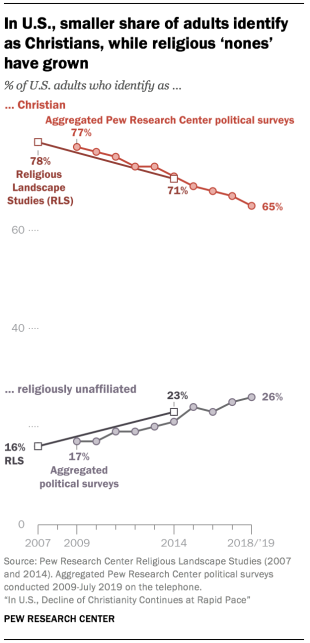

Decline of Christianity. As foretold in my 2009 mega-bestseller We Are Doomed, America is following western Europe into irreligion. If anything I underestimated the speed with which traditional religious belief is declining.

A Pew Research Center report dated October 17th has precise numbers:

The religiously unaffiliated share of the population, consisting of people who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or "nothing in particular," now stands at 26 percent, up from 17 percent in 2009.

Twenty-six divided by seventeen is 1.5294 and change, so we are 53 percent more irreligious today than we were when We Are Doomed emerged from the presses to stun and dismay the world.

Twenty-six divided by seventeen is 1.5294 and change, so we are 53 percent more irreligious today than we were when We Are Doomed emerged from the presses to stun and dismay the world.

I took care to qualify my 2009 prediction with:

Note please that what is weakening here is not the human instinct to spirituality. That is … a core feature of human nature, and not likely to go away, however much the celebrity atheists wish it to.

Supposing that's right, where does that "human instinct to spirituality" turn when traditional religion no longer nourishes it?

For those people whose neurology inclines them to the left (low scores on ingroup loyalty, respect for authority, and disgust) the commonest opinion, which I share, is that "woke" ideology, especially anti-racism, is what gets the spiritual juices flowing.

Supposing that's true on the left, what's the right equivalent? "Since 1992 the share of Americans with no religion has … trebled even among conservatives," says Ed West mulling over the numbers. (He doesn't give his source and I can't find it, but it doesn't seem improbable.) What hook are we irreligious conservatives going to hang our spiritual hats on?

Ed suggests a slide into intolerant ethnocentrism and demagogue-worship and writes, echoing theocon Ross Douthat: "If you don't like the Religious Right, you're really not going to like the Irreligious Right."

That's all a bit odd coming from Ed West, Brexiteer (although of the "soft" school) and author of The Diversity Illusion. Are irreligious conservatives really gap-toothed Yahoos yearning to prostrate themselves before some guy on a white horse? Or has the Progressive Hitlery-Hitlery-Hitler fixation infected part of Ed's brain?

As an irreligious conservative myself, I resist the thought. I don't know precisely how irreligious my faction, the Dissident Right, is overall, but I do know that I'll be speaking at the annual conference of the H.L. Mencken club on November 9th. (Irreligious? H.L. Mencken, hel-lo?) Sharing the speaker's platform with me will be several several other Dissident Right types whose intellectual accomplishments put my own meager academic qualifications to shame and whose teeth have no gaps between them at all.

The Z-man, to whom I look for inspiration on matters like this, hedges his bets:

With the fading of the American empire, new ideas are springing up at home and abroad. At some point, a new moral framework will coalesce to challenge the brittle dying orthodoxy. Alternatively, maybe what comes next is a new dark age. Perhaps this Progressive spasm is the last one before the lights go out.

Misleading advice. Forbes magazine, apparently in earnest, has urged young women to take solo hiking trips around Pakistan.

Pakistan. It's not exactly on every solo female traveler's bucket list. But that doesn't mean that it shouldn't be. Especially if you ask vlogger and content creator Eva zu Beck, who thinks Pakistan could be the world's No. 1 tourism destination. [This Popular Solo Female Travel Vlogger Thinks Pakistan Could Be The World's No. 1 Tourism Destination, by Breanna Wilson; Forbes, October 11th 2019]

The Twittersphere had considerable fun with that. The British lefty periodical New Statesman used to run a weekly competition wherein for readers to exercise their wit. One popular competition theme was "Misleading Advice for Foreigners."

The Twittersphere had considerable fun with that. The British lefty periodical New Statesman used to run a weekly competition wherein for readers to exercise their wit. One popular competition theme was "Misleading Advice for Foreigners."

- Try the famous echo in the British Museum Reading Room.

- London barbers are delighted to shave patrons' armpits.

And so on. Seems to me this Forbes article belongs exactly in that genre.

[Which is not totally extinct, although the only recent specimens I can find on the internet are (a) lame and (b) incomprehensible to non-Brits.]

Book reports. My reading recently has been a catalog of failure.

Fiction-wise, I bailed out from Ken Follett's Century Trilogy not far into the third book. That's out of character for me. I usually enjoy trilogies and tetralogies. I've reviewed more than my share—here, here, here, and here—and read many more, starting with Lord of the Rings around 1962. Yes, I was LOTR before LOTR was cool.

Follett's old-style leftism takes over the narrative in that third book, The Edge of Eternity, though, and he lost me. I don't mind old-style leftism as much as I mind crazy woke leftism, but it doesn't make for good fiction, not at this strength. Hey, Ken: You want to send a message, call Western Union.

Follett's old-style leftism takes over the narrative in that third book, The Edge of Eternity, though, and he lost me. I don't mind old-style leftism as much as I mind crazy woke leftism, but it doesn't make for good fiction, not at this strength. Hey, Ken: You want to send a message, call Western Union.

I did no better with nonfiction. I took Robert Merry's book about the James K. Polk presidency to China with me, for reading on trains and planes. Merry's not a gifted writer, though; I'm not as interested in mid-19th-century American history as I thought I was; and the book's seriously lacking in maps—there is just one. Of the 477 pages of narrative I got to page 269. Then I laid the book aside, and haven't picked it up since.

Now I'm getting worried that I may be slipping out of the book-reading community. Is this just a thing that happens as we age? Am I headed down the trail mapped by Philip Larkin, towards the same destination he arrived at: "Books are a load of crap"?

Or am I just being dragged along by the zeitgeist? Are books just fading from the smartphone-addicted, Netflix-binge-watching scene? I rarely see people reading a book on trains or planes any more. The last time I sat next to one such was on the Peking subway last month; the guy was reading Foucault's Words and Things in a Chinese translation (词与物). Good grief!

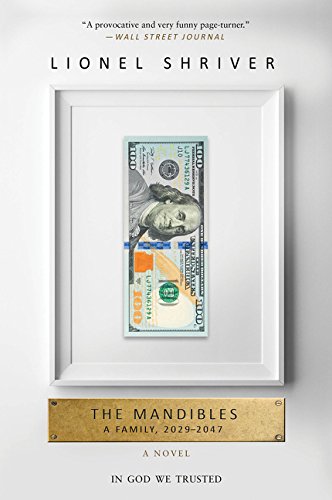

In hopes of getting back on the rails I've bought two novels recommended by friends: Lionel Shriver's The Mandibles and Jake Arnott's The Long Firm Trilogy. For nonfiction fiber I've also bought Kevin MacDonald's latest, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition.

On the audiobook front, I'm still listening to Scourby's reading of the King James Bible when I work out. I'm deep into the Epistles now, and finding Saint Paul a bit of a bore. The Gospels were OK, but I knew them pretty well from my schooldays—no surprises. So far the New Testament isn't half as entertaining as the Old.

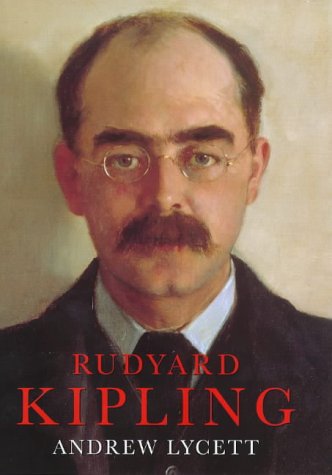

Kipling story. The centenary of Rudyard Kipling's poem "The Gods of the Copybook Headings," noted by me in the October 25th Radio Derb, was well received. I got several emails and at least one appreciative tweet.

Here's a Kipling story, from Andrew Lycett's fine biography.

Here's a Kipling story, from Andrew Lycett's fine biography.

In August [of 1921] Rudyard's listlessness called for another series of major and "very unpleasant" medical examinations. The X-rays, which required a bismuth meal in advance, showed "no sign of the always to be dreaded cancer." But an old ulcer was found—a large area of inflammation in the colon and lower bowel from which there had been a haemorrhage, which had caused his anaemia. Rudyard was put on a "no solids" diet and for a while lived on milk, enemas, and Epsom Salts. (This may well have been the occasion when Rudyard was examined rectally. He later joked, or so Oliver Baldwin liked to recount, "If this is what Oscar Wilde went to prison for, he ought to have got the Victoria Cross.")

Math Corner. The October 23rd op-ed in the Los Angeles Times titled Modern high school math should be about data science—not Algebra 2. Steve had some comments here, with Steve's usual better-than-average comment thread.

My own position is that, yes, a bit of data science—basic statistics—sure wouldn't hurt as a standard component of high-school math. Then perhaps I wouldn't encounter so many people who don't understand the difference in meaning between the words "some," "most," and "all." I might even—who knows?—occasionally find myself in conversation with a person who knows the meaning of the word "average."

From that op-ed:

When was the last time you divided a polynomial? If you were asked to do so today, would you remember how? For the most part, students are no longer taught to write cursive, how to use a slide rule, or any number of things that were once useful in everyday life. Let's put working out polynomial division using pencil and paper on the same ash heap as sock darning and shorthand.

Yeah, I see their point. I have a lingering affection for the old stuff, though. I still have a slide rule here in my desk drawer. Useless, now, of course, and it would be a crime to teach it to ordinary high-schoolers, but …

And some of my old stuff is real old. I am sure I belong to the last generation that was taught in school how to extract a square root by the "long division" method—so called because the computation is laid out like an old-fashioned long division: dividend under a "shed," divisor to the left, quotient on the shed roof.

Here's an example from Rose's New Arithmetic, "An explanatory and practical arithmetic adapted to the business and commerce of the United States" by John Rose. (Philadelphia: Sower & Barnes, 1853). Rose rearranged the "shed" some, but it's the same idea.

There is a similar style of hand computation for cube roots.

I didn't learn this one in my 1950s schooling, but I wish I had. It was a common feature of nineteenth-century college algebra textbooks. Here's the method described in The Scholar's Arithmetic, or Federal Accountant by Daniel Adams, M.B. (Printed and sold by John Prentiss at the Rensslauer Bookstore; Troy, NY, 1808).

An appalling waste of time and intellection? Eh, maybe. But:

Kummer, like all other great mathematicians, was an avid computer, and he was led to his discoveries not by abstract reflection but by the accumulated experience of dealing with many specific computational examples. The practice of computation is in rather low repute today, and the idea that computation can be fun is rarely spoken aloud. Yet Gauss once said that he thought it was superfluous to publish a complete table of the classification of binary quadratic forms "because (1) anyone, after a little practice, can easily, without much expenditure of time, compute for himself a table of any particular determinant, if he should happen to want it … (2) because the work has a certain charm of its own, so that it is a real pleasure to spend a quarter of an hour in doing it for one's self, and the more so, because (3) it is very seldom that there is any occasion to do it." One could also point to instances of Newton and Riemann doing long computations just for the fun of it … [A]nyone who takes the time to do the computations [in this chapter of Professor Edwards's book] should find that they and the theory which Kummer drew from them are well within his grasp and he may even, though he need not admit it aloud, find the process enjoyable.

—Harold Edwards, Fermat's Last Theorem, as quoted in Chapter 13 of my book Unknown Quantity.

John Derbyshire [

John Derbyshire [