Crossposted from Amren.com, with links added by VDARE.com.

Ricardo Duchesne is a historical sociologist and professor at the University of New Brunswick. Best known as the author of the important study The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (2011), he is also the founder of the Council of European Canadians, whose website publishes articles of interest to American Renaissance readers. AR has also reported on his battles with the Canadian multicultural establishment.

Prof. Duchesne’s latest book (Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadian) which describes how Canada succumbed to multiculturalism and mass immigration, is divided into four parts. First, the author recounts the early French and British settlement of the land, contrasting this historical reality with today’s propagandistic histories that project multiculturalism back into the past. Second, he criticizes multicultural theory and the scholars who promote it—particularly Prof. Will Kymlicka, who has become the de facto chief ideologue of the destruction of Canada. Third, he criticizes assimilationism, currently considered the “right wing” alternative, finding it even worse than multiculturalism. Fourth, he recounts the evolution of Canadian immigration policy since the Second World War, demonstrating its inherent tendency to become more liberal over time.

Prof. Duchesne’s latest book (Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadian) which describes how Canada succumbed to multiculturalism and mass immigration, is divided into four parts. First, the author recounts the early French and British settlement of the land, contrasting this historical reality with today’s propagandistic histories that project multiculturalism back into the past. Second, he criticizes multicultural theory and the scholars who promote it—particularly Prof. Will Kymlicka, who has become the de facto chief ideologue of the destruction of Canada. Third, he criticizes assimilationism, currently considered the “right wing” alternative, finding it even worse than multiculturalism. Fourth, he recounts the evolution of Canadian immigration policy since the Second World War, demonstrating its inherent tendency to become more liberal over time.

History and propaganda

Canadian undergraduates are assured by their history textbooks that “from the very beginning, the land that became Canada was a multiracial place, the destination of a constant flow of new immigrants of varying ethnicities.” The purpose of such deception is, of course, to disarm any skepticism about current Third World immigration by making it appear to be a mere continuation of Canadian history. One aspect of the deception is to broaden the term “immigrant” to include pioneers coming to a wilderness, not people merely moving from one country to another.

Today’s textbooks begin with highly positive accounts of the “First Nations” who “lived in a reciprocal relationship with nature,” “exhibited none of the negative features of capitalistic society,” and had tools “superior to what the Europeans could offer.” Contemporary historians like to accuse their predecessors of “suppressing” Indian “voices,” but as Prof. Duchesne points out, all of their own sources are European as well. What is new is not that the Indians have been freed to speak for themselves, but that white historians are now determined to use them as “pawns to serve contemporaneous political agendas.”

Prof. Duchesne disputes the propriety of the fashionable expression “First Nations” as applied to the Huron, Algonquins, Cree, and Iroquois, noting that nations usually have defined borders, formal armies, a legal code, and other characteristics of civilized life that these tribes lacked. He also notes a kind of incoherence on the part of multicultural historians: They depict white settlers as oppressing and silencing the Indians, but simultaneously convey the impression that Indians were also partners in creating Canada.

The truth is that settler/Indian relations were:

interactions between separate peoples, commercial and military interactions which affected both sides, but which essentially involved the modernizing encroachment of the Anglo-French side upon the Amerindian cultures, leading to a situation in which, by the time of Confederation in 1867, only 1 percent of the population of Canada was Amerindian.

When the British took over in 1760, about 10,000 French settlers had grown through natural increase to a population of 70,000. British efforts to Anglicize Quebec ran aground on French Canadian fertility, for a long time the highest anywhere in the Western world at 5.6 surviving children per woman. It was called the “revenge of the cradles,” and it resulted—with essentially no further arrivals from France—in a French-Canadian population of four million by 1950. In other words, French Canada was created not via immigration, as contemporary historians wish to convince impressionable students, but from a small settler population that increased rapidly.

The first large-scale settlement of English speakers involved some 50,000 Loyalists arriving from the 13 colonies to the south, mostly during the 1780s. It would be at best misleading to describe them as “immigrants from the United States,” however; they were British subjects migrating within North America out of opposition to the colonial war of independence. Rather than moving to Quebec, most settled the sparsely populated Atlantic Provinces and “Upper Canada,” the future Ontario.

Contemporary historians speak of 3,000 black and 2,000 Amerindian “loyalists” arriving as part of this migration, but these non-whites constituted no more than seven percent of the total, and nearly half of the blacks emigrated back to Africa. Yet Duchesne found one history textbook with longer sections devoted to “The Blacks” and “The First Nations” than to the English!

The first large-scale immigration to Canada occurred between 1815 and 1850, but nearly all of the one million or so new arrivals came from the British Isles. Multiculturalists do the best they can with this disagreeable data by talking up the regional diversity within Britain and suggesting earlier historians had naively believed in a “monolithic” British culture. They enjoy contrasting the “complexity” and “nuance” of their own view of Canadian history with their predecessors’ “simplistic" narrative of “two founding populations.”

After Confederation in 1867, the Canadian government tried to attract new arrivals from Europe, partly “in order to settle the Western prairies and ensure Canada’s sovereignty over this huge area.” Before about 1896, they had little success; Canadians leaving for the United States outnumbered immigrants from Europe. At this time, the largest ethnic group after the French and British were Germans, numbering 203,000, or 6 percent of the population, by 1871. The most significant non-European immigration involved 15,000 Chinese brought in around 1879 to help build the transcontinental railroad.

Between 1896 and 1914, two and a half million immigrants arrived in Canada. The new arrivals certainly increased the intra-European diversity of the country, since they included significant numbers of Scandinavians, Ukrainians, Polish, and Italians, along with smaller numbers of other European nationalities. There were some arrivals from Asia at this time, although they never amounted to more than two percent of total immigration. The government soon acted to prevent more from coming: Immigration from India was prohibited after 1907, and Asian immigration was stopped altogether by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923. In 1931, the ethnic Chinese—by far the largest Asian group—numbered 46,519 out of a total population then approaching ten million. The white proportion of the population actually rose in the early 20th century, from 96 percent in 1901 to 97.5 percent in 1921.

In sum, says Prof. Duchesne:

It is a historical falsehood to say that Canada has always been a diverse nation. Canada was created by Europeans; all the institutions, legal system, educational curriculum, transformation of wilderness into productive farms, all the cities, the parliamentary traditions, the churches, the entire infrastructure of railways, ports, shipping industries and highways were created by hardworking Europeans.The author notes that multicultural historians sometimes acknowledge this in an effort to inculcate guilt in white students for the supposed mistreatment or exclusion of non-whites, but usually return quickly to the narrative that Canada was multicultural from the beginning. As he remarks, “This is how the mind of the left operates.”

Prof. Duchesne discovered a wonderfully apt prophecy of current Canadian historiography fashions in the words of Canadian historian Donald Creighton, who died in 1979:

History must be defended against attempts to abuse it in the cause of change; we should constantly be on our guard against theories which give [the past] a drastically new interpretation to sanction a major program of change. A nation that distorts its past runs a grave danger of forfeiting its future.Canada’s ideologist-in-chief

Canada’s transformation has offered extraordinary opportunities for academics who promote the zeitgeist. Most remarkable has been the career of a certain Will Kymlicka, who has seen his writings translated into 32 languages and has become wealthy from the grants and awards he has been given every year since graduate school. “Although he fashions himself as an outsider fighting the dominant Eurocentric discourse,” remarks Prof. Duchesne, “he is Canada’s premier government-sanctioned ideologue of multicultural citizenship.” His popularity with Canadian elites is probably due to his advocacy of Canadian multiculturalism as a model for the rest of the Western world. He spends a lot of time in Europe, where he assures his audiences that multiculturalism has proved a stunning success in Canada.

Canada’s transformation has offered extraordinary opportunities for academics who promote the zeitgeist. Most remarkable has been the career of a certain Will Kymlicka, who has seen his writings translated into 32 languages and has become wealthy from the grants and awards he has been given every year since graduate school. “Although he fashions himself as an outsider fighting the dominant Eurocentric discourse,” remarks Prof. Duchesne, “he is Canada’s premier government-sanctioned ideologue of multicultural citizenship.” His popularity with Canadian elites is probably due to his advocacy of Canadian multiculturalism as a model for the rest of the Western world. He spends a lot of time in Europe, where he assures his audiences that multiculturalism has proved a stunning success in Canada.

Prof. Kymlicka [Email him] expounded his ideas fully in Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights (1995), a 240-page book to which all of his extensive subsequent writing has added little. His central idea is that Canada is a civic nation into which nearly anyone can integrate regardless of race or color. The only exceptions are those who maintain inherently illiberal, coercive cultural practices such as forced marriages and female circumcision. But Prof. Kymlicka asserts that few immigrants to Canada have been unwilling to abandon such practices.

Prof. Kymlicka also believes that the Canadian government should support ethnic rights for minorities, including the sorts of preferences known in the US as “affirmative action,” financial subsidies for cultural practices, representation in the media, multicultural educational curricula, dual citizenship, and exemption from some rules that violate minority religious practices.

Prof. Kymlicka also believes that the Canadian government should support ethnic rights for minorities, including the sorts of preferences known in the US as “affirmative action,” financial subsidies for cultural practices, representation in the media, multicultural educational curricula, dual citizenship, and exemption from some rules that violate minority religious practices.

Prof. Duchesne makes three criticisms of Prof. Kymlicka’s position. First, it completely ignores the ethnic British identity of the Canadian majority. Prof. Kymlicka has nothing positive to say about the British who founded Canada. Unlike racial and religious minorities, in his system, they are not meant to enjoy any ethnic identity, but only a thinner, civic type of identity.

The English societal culture is portrayed as a deracinated, neutralized sphere consisting of modern conveniences—economic, educational, and social institutions—intended “in principle” to serve anyone regardless of cultural background. Anglo-Canadians are mere possessors of individual rights, whereas every other ethnic group enjoys both individual and group rights.Of course, Prof. Kymlicka is aware that some Euro-Canadians are still attached to their ethnic identity and not satisfied with a merely civic identity. He refers to such people as “racists” and “xenophobes,” and recommends combining the cultural accommodation of racial minorities with punishment for such whites. Prof. Kymlicka never tries to defend this double standard; he presents it as natural and uncontroversial.

Prof. Duchesne also criticizes Prof. Kymlicka for assuming that majority ethno-cultural rights inherently contradict liberal principles. He points out that the European nation states that developed the strongest liberal traits—including Britain, France, Scandinavia, the Low Countries, and Italy—were relatively homogeneous, while multinational empires such as Austria-Hungary remained “enraptured by illiberal forms of ethnic nationalism and intense rivalries over identities and political boundaries.” The multicultural experiment is not a consequence of liberalism, but a serious threat to it.

“Civic identity,” the currently fashionable notion that Western nations are based on universal principles to which any human being can assimilate, was, according to Prof. Duchesne, the invention of Jewish political theorist Hans Kohn in a book first published in 1944. Kohn’s ideas have since been extended, by writers such as the Marxist Eric Hobsbawm, into a doctrine that nations are “artificial historical constructs” developed by political elites. Appeals to “myths of common descent” are, on this view, a mere ideological weapon invented by those elites to gin up popular support for their rule. Prof. Duchesne mentions a couple writers who have challenged these fashionable theories, but so far, they have been constrained by a desire not to appear “racist.”

In any case, he concludes that “western liberal nations were not founded in the absence of an existing ethnic collectivity, and certainly not for the purpose of mixing the races of the world within one state.”

Prof. Duchesne’s third and most important criticism of Prof. Kymlicka is that he regularly refers to long established minorities such as the Amerindians and Quebecois when expounding his theories of group rights, while surreptitiously using those theories to justify, if not insist on, the introduction of countless new ethnic minority groups through immigration. In other words, because there have long been minorities to whom certain rights are due, Canada should encourage the arrival of yet more minorities. Under the pretext of protecting minority rights, he smuggles in a requirement that Western nations accept a constant flow of foreigners. He implies that the liberal constitution of Western nations make this a moral imperative.

There is nothing in Prof. Kymlicka’s paradigm that would keep it from being applied to African or Asian nations, but he has no apparent interest in doing so. He writes, for example, of requiring the dominant majority “to abandon attempts to fashion public institutions solely in its own national (typically white/Christian) image.” But dominant majorities are not white and Christian in large parts of the world; that is the hallmark of Western nations, and thus it is evident that multiculturalism and mass immigration are meant exclusively for them. As Prof. Duchesne notes, this is a “manipulation of the liberal values of Westerners” aimed at reducing them to a powerless minority uniquely deprived of group rights in the countries their ancestors founded.

Like other proponents of mass immigration, Prof. Kymlicka presents his theory as a realistic response to globalization, writing that “massive numbers of people are moving across borders, making virtually every country more polyethnic in composition.” But this is simply untrue in large parts of the world, as Prof. Duchesne demonstrates, and it is true in the West largely due to the influence of people who think like Prof. Kymlicka. In other words, multiculturalism is not a response to any preexisting challenge of mass migration; it is a program (as Prof. Kymlicka elsewhere admits) for “profound transformation” by means of immigration. Transformation is the contemporary Left’s preferred term for what their more forthright predecessors called revolution.

As previously noted, Prof. Kymlicka calls Canada’s multicultural experiment a splendid success, but he does not appear to have devoted much effort to testing that success; Prof. Duchesne has found about 15 pages in his work devoted to this question. There are several ways one might test success: determine the economic effects of immigration, study how well newcomers adjust to Canada and how well native Canadians adjust to them, or investigate the other consequences of increased diversity.

Prof. Kymlicka’s remarks on the supposed economic benefits of immigration do not go beyond what anyone can pick up in the mainstream media. But Prof. Duchesne found one detailed study [PDF] by a retired Canadian professor of economics, Herbert Grubel. Prof. Grubel found that the average immigrant arriving since 1986 has imposed an annual fiscal burden on Canadian taxpayers of $6,000, for a total of $25 billion annually for all immigrants. Much of this burden comes because parents and even grandparents “join their families in Canada, pay virtually no taxes and consume large amounts of government services, especially health care.” Some acquire dual citizenship and continue to live abroad, paying no taxes and coming to Canada only to consume government services.

Prof. Kymlicka’s remarks on the supposed economic benefits of immigration do not go beyond what anyone can pick up in the mainstream media. But Prof. Duchesne found one detailed study [PDF] by a retired Canadian professor of economics, Herbert Grubel. Prof. Grubel found that the average immigrant arriving since 1986 has imposed an annual fiscal burden on Canadian taxpayers of $6,000, for a total of $25 billion annually for all immigrants. Much of this burden comes because parents and even grandparents “join their families in Canada, pay virtually no taxes and consume large amounts of government services, especially health care.” Some acquire dual citizenship and continue to live abroad, paying no taxes and coming to Canada only to consume government services.

As in the United States, the broad effect of mass immigration is to lower wages for working Canadians while allowing businesses to profit from cheap labor. According to a recent Canadian census, between 1980 and 2005, the incomes of the bottom fifth of earners fell by an average of 20.6 percent; those of the the top fifth increased by 16.4 percent.

It is difficult to measure how well immigrants are managing in Canada, as it involves subjective judgment and is affected by individual circumstances. Polls show most new arrivals saying they are happy in Canada, but as Prof. Duchesne remarks, this may mean no more than that they are pleased to benefit from quotas, preferences, and financial support for starting businesses, and find themselves better off than in their countries of origin.

On the subject of Muslim terrorism, Prof. Kymlicka can point out truthfully that Canada has so far largely been spared the sorts of attacks suffered in Europe and the United States. He often mentions that the percentage of immigration to Canada from Muslim lands is small, but this does not mean he wants to keep that percentage small. He blames jihad attacks in Europe on a “lack of support for Muslim immigration by European taxpayers,” so when attacks begin in Canada, he is likely to argue for rewarding the perpetrators’ “communities” with more generous subsidies.

Prof. Kymlicka asserts there is little evidence of “entrenched racial concentration in poor ghettos,” yet this is belied by the Canadian media. The National Post reported in 2012 that “In 1981, Canada had only six neighborhoods with ethnic enclaves . . . . Now that number has mushroomed to more than 260.” A study published the same year by Citizenship and Immigration Canada states that “in Toronto and Vancouver, the degree of separation between Whites and visible Minorites is projected to rise considerably.”

Some immigrant groups, notably West Indians, are considerably overrepresented in the country’s crime statistics, but Prof. Kymlicka considers such numbers “old-fashioned racism.”

One might think it important to consider not only how well immigrants are adjusting to Canada, but how well Canadians are adjusting to immigrants. Prof. Duchesne found a poll from 2013 in which 61.7 percent of respondents agreed that “less immigration” would lead “to a better future 25 years from now.” When Prof. Kymlicka finds evidence of growing acceptance, he produces it triumphantly, but when he finds evidence that white Canadians are not happy with immigration, he treats this as proof of continuing “white racism” which must be crushed.

Finally, Prof. Kymlicka argues that multiculturalism leads to “cultural enrichment,” but it is not possible to examine his basis for this, as he treats it as self-evident. As Prof. Duchesne puts it, he never explains to readers “what’s so lacking about Euro-Canadian culture and what’s so amazing about African, Asian and Islamic culture.”

Prof. Kymlicka’s preferred policies, which by his own admission would reduce whites to “a constantly shrinking minority,” will strike most readers as fairly radical, but he has many critics to the left. They view his retention of a liberal civic culture in which all Canadians are meant to participate as nothing more than a way to “stabilize white supremacy.” Instead, they demand that newly arrived ethnicities be allowed to establish their own institutions without any subservience to a liberalism of inescapably European origin: It is not for whites to dictate the terms under which non-Europeans are allowed to participate in Canadian life. Even drawing distinctions between “good” and “bad” Muslims is a form of discrimination which dehumanizes those who follow Islam more strictly. White supremacy will never be defeated, say the radicals, until anyone and everyone who wants to come to Canada is given the right to immigrate and establish whatever institutions they wish. In short, the multicultural project requires the complete abolition of the Canadian state.

As Prof. Duchesne mentions, the radicals promoting these extravagant ideas wield enormous power in universities and control many publishing houses and academic journals. They keep “moderate” multiculturalists walking on eggshells with anxiety about their own possibly “racist” attitudes, and virtually no one stands up to them.

Assimilation is no solution

The official “conservative” alternative to current Canadian policy is assimilationism, which rejects multiculturalism but not mass immigration. According to this view,

immigration would 'work' if only immigrants were encouraged to assimilate to 'Canadian values.' They want the government and the educational institutions to encourage a sense of Canadian citizenship and loyalty to Canada’s liberal democratic culture. They firmly believe that any immigrant group (with the possible exception of radical Muslims) is capable of disaggregating itself into individual units to become average Canadians. So long as ethnic group identification is discouraged, Canada can remain Canada even if European Canadians are eventually reduced to a tiny minority.To assimilationists, the emphasis Prof. Kymlicka and his kind place on identity politics and group rights for minorities proves multiculturalists to be “the real racists.”

In other words, assimilationists are wholly innocent of racial reality. They ignore both the evidence of racial differences in behavioral patterns and intelligence, and the inescapable reality of the universal human tendency to identify with and favor those genetically and culturally most similar to oneself. Assimilationists align with the Left in viewing it as a malady of purely cultural origin that must be rooted out.

Prof. Duchesne actually prefers the multicultural position that human beings are born into particular ethnic cultures (although he sees these as partly rooted in race), and that ethnic groups have every right to perpetuate and protect their culture and ethnic self-interests. He differs from multiculturalists primarily in refusing to exempt whites people from these principles: “Only by speaking up front about the ethnic interests of Euro-Canadians can we mount a proper challenge to the otherwise impending reduction of Euro-Canadians to minority status in Canada.”

The self-radicalizing character of multiculturalism

Nationalists have often wondered why Western nations—and only Western nations—adopt policies that guarantee their long-term oblivion. Is it some weakness unique to our race? If so, why did it never manifest itself until the later part of the 20th century?

European man is unusual in his individualism, de-emphasis of kinship relations in favor of contractual relations, low ethnocentrism, and a morally universalistic outlook. Given these evolutionary realities, it is not an accident that liberalism was created by European man. Liberalism views society as a quasi-contractual relationship between individuals aimed at allowing everyone to pursue private aims, particularly economic self-interest, free from the “burden” of inherited traditions. As Prof. Duchesne notes, liberals “don’t want to admit that liberal states, like all states, were . . . created by a people with a common language, heritage, racial characteristics, religious traditions, and a sense of territorial acquisition involving the derogation of out-groups.”

The German jurist Carl Schmitt theorized that liberals have an inherently weak sense of the political, because they are universalists, and politics is essentially about competition between groups, which rests on an ability to distinguish friends from enemies. For many generations, writes Prof. Duchesne, Western nations’ “sense of ethno-cultural identity was the one collectivist norm holding their liberal nations safely under the concept of the political.” Once this last form of collectivism was abandoned, liberal nations lost the ability to see outsiders as a threat. They were caught up in a “spiral of radicalization” that would lead to the importation of countless people from collectivist cultures who do not hesitate to use liberal language against their hosts to promote their own collective interests. Such people are not themselves liberals, and are unwilling to limit themselves to the pursuit of private and economic interests; they aim at gaining control of territory for their own group. Hence, the “no-go” immigrant zones in contemporary European countries, which liberal multiculturalists did not know to expect.

Towards minority status

The final section of Canada in Decay describes the breakdown of Canadian identity following the acceleration of liberalism after the Second World War.

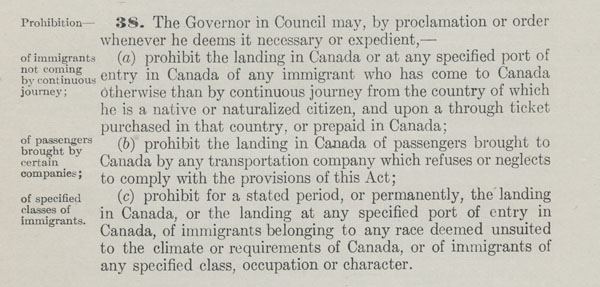

In the early 20th century, Canada was overtly a white man’s country. No one spoke of “human rights,” but there was a widespread notion of British liberties, which included freedom of speech, religion and association. Freedom of speech included the freedom to express distaste for certain groups, and freedom of association included the right to refuse to hire or serve them. Aboriginals were kept on reserves, and neither they nor Asian immigrants enjoyed automatic voting rights in all provinces. The Immigration Act of 1910 gave the Cabinet the right to enact regulations barring immigrants “belonging to any race deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” Asians were specifically excluded by legislation passed in 1923. There were concerns that increasing intra-European diversity might be weakening the country’s specifically British character.

The Second World War was by far the most destructive conflict in human history, and the defeated Germans had emphasized race. Following the Allied victory, race denial emerged from the cult-like atmosphere of Boasian anthropology and achieved wider appeal as the supposed key to preventing similar wars in the future. In 1950, the doctrine was endorsed by the United Nations in its “Statement on Race,” drafted by Ashley Montagu:

The Second World War was by far the most destructive conflict in human history, and the defeated Germans had emphasized race. Following the Allied victory, race denial emerged from the cult-like atmosphere of Boasian anthropology and achieved wider appeal as the supposed key to preventing similar wars in the future. In 1950, the doctrine was endorsed by the United Nations in its “Statement on Race,” drafted by Ashley Montagu:

the ethnic inequalities of the world, the wealth of European nations and the poverty of non-European nations, the impoverished status of blacks and aboriginals in the United States and the West generally, were a result of the discriminatory policies [and] colonizing activities of Europeans rather than a result of differences in aptitudes.As in other Western countries, politicians in Canada began to respond to the new intellectual atmosphere. A Standing Committee of the Canadian Senate recommended that the Immigration Act of 1910 be revised, avoiding explicit reference to race while maintaining “Canada’s traditional pattern of immigration and her strong European orientation.” The term “ethnic group” became the euphemism for race in the new regulations adopted in 1952. At first, ethnicity was meant to connote biological differences, although not hierarchies; only gradually was it interpreted as a wholly cultural concept.

Government authorities ceased justifying the exclusion of blacks because it was better for Canadians. Instead, in 1952, the Immigration Minister explained that blacks should be kept out because “it would be unrealistic to say that immigrants who have spent the greater part of their life in tropical and subtropical countries become readily adapted to the Canadian mode of life which, to no small extent, is determined by climatic conditions.”

Government authorities ceased justifying the exclusion of blacks because it was better for Canadians. Instead, in 1952, the Immigration Minister explained that blacks should be kept out because “it would be unrealistic to say that immigrants who have spent the greater part of their life in tropical and subtropical countries become readily adapted to the Canadian mode of life which, to no small extent, is determined by climatic conditions.”

Others pointed out the desirability of excluding those who might cause racial tension in the future: “Canada has no racial problem, nor has Canada a racial policy. And that is the way it's going to stay,” said a later immigration minister. Prof. Duchesne summarizes:

The consensus around these years [the 1950s] was that Canada would not discriminate against non-Whites who were already citizens in Canada, would avoid using racial language in its immigration act, but would nevertheless affirm its British-European national character and its wish to maintain that character.Some groups were already taking a more radical position, however. The Canadian Congress of Labor recommended an end to all racial considerations in immigration policy. Jewish groups such as the Canadian Jewish Congress began to move beyond fighting the perception that Jews were unassimilable aliens to embrace a grand strategy of allying themselves with other minority organizations in a campaign against all discrimination.

These efforts began to bear fruit. In 1960, the government announced that it would seriously work on a new immigration policy that would eliminate all discrimination. Note that this was only eight years after passage of the 1952 regulations, whereas the previous 1910 law had endured for forty-two years.

The Immigration Regulations adopted in 1962 replaced racial criteria with “skills based” criteria. However, in official but unpublicized papers, authorities specified that immigrants from non-European countries would be able to sponsor only their immediate families, whereas Europeans could sponsor other relatives as well. Officials voiced the view that there was nothing wrong with focusing on recruiting immigrants from European (and European-created) nations.

Commonwealth countries objected, however, and the authorities no longer had enough self-confidence to tell them Canada’s immigration policies were none of their business. In November 1965, Prime Minister Lester Pearson promised to remove all barriers to the acceptance of non-white immigrants.

The new regulations adopted in 1967 created a points system, scoring applicants on education and training, personal character, knowledge of French or English, presence of relatives in Canada, and employment opportunities in their destination region. Those thought likely to benefit Canada economically were accepted. For the first time, immigration processing facilities were opened outside Europe. Many no doubt continued to hope that a skill-based determination would continue to exclude most people from the Third World, but the proportion of immigrants from Asia and the Caribbean rapidly increased from 10 percent in 1965-66 to 23 percent in 1969-70. The total number of immigrants also began to increase.

The work of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism shows how quickly elite opinion was shifting. Widely seen as an effort to defuse Quebecois separatism, this commission was established in the summer of 1963 by Lester Pearson to “recommend what steps should be taken to develop the Canadian Confederation on the basis of an equal partnership between the two founding races, taking into account the contribution made by the other ethnic groups.”

The Commission rejected not only Pearson’s old-fashioned talk of the “two founding races,” but even any concept that Canada was ethnically British and Quebecois. For these ideas they substituted the weaker concept of biculturalism: that Canada is populated by people with a shared French and Anglo culture. Yet by the time the commission issued its final report, the strongly anti-nationalist Pierre Trudeau was Prime Minister, and found even this too restrictive. In October 1971, he rejected the Commission’s findings, saying: “biculturalism does not properly describe our society; multiculturalism is more accurate.” The state must be neutral not only with regard to race or ethnicity, he proclaimed, but even to culture. All cultures were henceforward to be seen as private matters, like religion. Canadian leaders would have to “separate once and for all the concepts of state and nation.”

For Trudeau, [writes Prof. Duchesne] the atrocities of the Second World War were inherent to the very nature of nationalism itself. The 'very idea of the nation state is absurd,' he wrote in 1962. An inescapable reality of nation states was the identification of the nation with an ethnic majority to the exclusion of other ethnic groups. This resulted in a situation in which minorities would always be striving to carve out their own states against the majority, and indeed against other minorities within their own lands, leading to constant tension and divisions.Incredible as it may seem, Trudeau thought deemphasizing common national concepts and promoting multiculturalism would decrease ethnic tensions. Indeed, Trudeau expected Canada to become a model for the world:

Canada could offer an example to all those new Asian and African states . . . who must discover how to govern their polyethnic populations with proper regard for justice and liberty. Canadian federalism is an experiment of major proportions . . . a brilliant prototype for the molding of tomorrow’s civilization.In declaring Canada multicultural, Trudeau was not describing it as it existed at that time, with a population still 96 percent European; he was instituting a program for the future. As his supporter Hugh Forbes noted, the success of multiculturalism would “obviously depend on the deliberate diversification of the Canadian population.” Between 1971 and 1981, a total of 1.5 million immigrants arrived in Canada, of whom 33 percent came from Asia, 16 percent from the Caribbean and South America, and 5.5 percent from Africa.

A directorate was set up within the Department of the Secretary of State in 1972 to help cultural groups “retain and foster their identity” and promote “creative exchanges among all Canadian cultural groups.” The cost was $200 million Canadian dollars, or $1.25 billion in today’s money. In 1973, an entire Ministry of Multiculturalism was established.

None of these changes were a response to popular demand. Gallup polls of the 1960s found that two-thirds of Canadians were opposed to all immigration. By 1975, the government was encountering enough resistance to organize public hearings, leading to the tabling of the so-called Green Paper in the House of Commons. The key message of the Green Paper was that Canadians were “concerned about the consequences for national identity that might follow any significant change in the composition of the population.”

A Special Joint Committee was set up supposedly to deal with these concerns. It received nearly 2,000 letters of opinion, formal briefs, and oral testimonies from Canadians, with a majority of 83 percent favoring firmer controls on immigration from the Third World. Some even demanded deportation of all non-whites and the restriction of immigrants to Anglo and Nordic countries only.

All such sentiment was ignored by the committee, which paid attention exclusively to delegations from organized minority groups voicing complaints about “racists and bigots.” The committee’s eventual recommendations included more legislation to protect immigrants from discrimination, and the re-education of native Canadians through funding for community programs to promote “intercultural understanding.”

In 1976, yet another new set of immigration regulations was established, now including refugees and “persecuted and displaced persons” as formal categories, and further broadening family reunification. The following year, Parliament passed the Canadian Human Rights Act, which included the first “hate speech” provisions criminalizing criticism of minority groups and threatening imprisonment for anyone who opposed mass immigration.

This Act, [comments Prof. Duchesne] together with other legislative measures, increased the responsibility and power of judges and lawyers, and thereby reduced the power of elected representatives. Human rights formulated by cosmopolitan elites and imposed from above would trump the rooted cultural norms of Canadians. As Hugh Forbes enthusiastically put it, the role of judges and courts would be “to suppress the negative or discriminatory reactions of the dominant or majority group to the increasing presence of others.”Trudeau was vague about how a multicultural Canada would be governed. How would the competing claims of Sharia law and Canadian law, for example, be settled? A large body of legal theory has grown up since the 1970s to try to clarify such matters, but Prof. Duchesne notes that most of it is highly abstract and ignores continuing immigration. What will decide the matter is not dry theory but demography. Once a city has a solid Muslim majority, it will be governed by Muslim law, no matter what the Canadian constitution says.

One final barrier to the full transformation of Canada survived the Trudeau administration. Although the ethnic composition of immigration had radically changed, the impact of these changes was limited by the responsiveness of the immigration system to the requirements of the labor market. Thus, despite the increased proportion of non-whites coming into Canada, the total number arriving fell as low as 86,000 per year during the recession of the 1970s. It was Trudeau’s “conservative” successor Brian Mulroney who ensured that immigrants would flood in at a rate of a quarter of a million a year, working-class wages be damned. A total population of 25 million when Mr. Mulroney took over in 1984 has now expanded to 35 million, largely through non-white immigration.

By 2040, Euro-Canadians are projected to become a minority in the country their ancestors built, and to fall to 20 percent a century from now.

F. Roger Devlin is a contributing editor to The Occidental Quarterly and the author of Sexual Utopia in Power: The Feminist Revolt Against Civilization.

F. Roger Devlin is a contributing editor to The Occidental Quarterly and the author of Sexual Utopia in Power: The Feminist Revolt Against Civilization.

The history of Canada began with the founding of Quebec by Samuel Champlain in 1608. The colony struggled in its early decades. In 1666, on orders from the French Court, Jean Talon took the first census of New France, counting 2,034 men and only 1,181 women. He convinced the mother country to send over several hundred girls of marriageable age and instituted fines for bachelors, bonuses for babies, and pensions for fathers of large families. By the time Talon left six years later, there were so many new children that the population had more than doubled.

The history of Canada began with the founding of Quebec by Samuel Champlain in 1608. The colony struggled in its early decades. In 1666, on orders from the French Court, Jean Talon took the first census of New France, counting 2,034 men and only 1,181 women. He convinced the mother country to send over several hundred girls of marriageable age and instituted fines for bachelors, bonuses for babies, and pensions for fathers of large families. By the time Talon left six years later, there were so many new children that the population had more than doubled.