The Republic of Ireland has just made it easier to get divorced in a May 23 referendum supported by an amazing (given how Ireland was as recently as the 1960s) 82% of voters [Ireland Votes Overwhelmingly to Ease Divorce Restrictions, by Ed O’Loughlin, New York Times, May 26, 2019]. Until now, Irish people wishing to get divorced had had to endure a cooling off period of four years from the date of applying for a divorce to it actually being granted. [Ireland’s Anti-Christian Revolution, Piers Shepherd, Chronicles, February 7, 2019] The plebiscite has cut this to just two years. We know this means more children raised by single mothers. Unfortunately, the evidence is that this has consequences for the children—and for countries.

In the USA, of course, divorce is already far easier and this is reflected in the composition of US households. In 1950, 93% of American children lived with both of their parents, parents who had signaled their commitment to each other through marriage. This created obvious stability for American kids: mother looked after the home, father was the main breadwinner and they were very unlikely to find some strange adult imposing themselves on their lives. By 2016, life was very different for a large minority of American children. Only 69% of them lived in two-parent households; 23% of them were being raised by single mothers [The Majority of Children Live With Two Parents, Census Bureau Reports, United States Census Bureau, November 17, 2019]; only 62% living with both biological parents. [More Than 60% of U.S. Kids Live with Two Biological Parents, by Nicholas Zill, IFS, February 2, 2015]

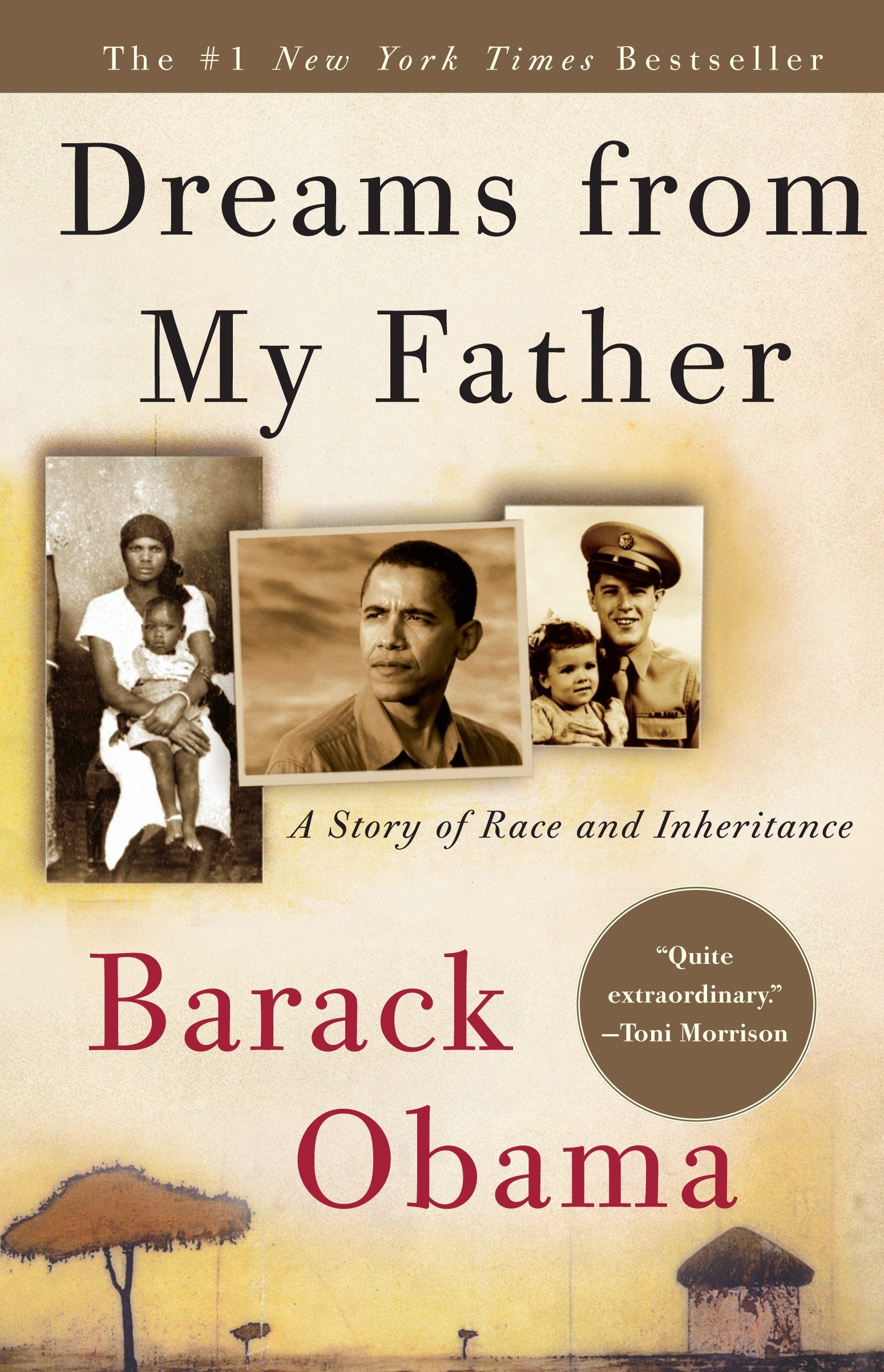

In 2016, American even elected a president who’d been twice divorced, his marital breakdowns leaving children between the ages of 15 and 6 in unstable family circumstances, likely not seeing their father as much as children traditionally would. He succeeded a president from a broken home, author of a book entitled Dreams From My Father, who in his childhood hardly ever saw his father at all.

In 2016, American even elected a president who’d been twice divorced, his marital breakdowns leaving children between the ages of 15 and 6 in unstable family circumstances, likely not seeing their father as much as children traditionally would. He succeeded a president from a broken home, author of a book entitled Dreams From My Father, who in his childhood hardly ever saw his father at all.

What does this increasing phenomenon of father absence do to the psychology of those who experience it? And, as they now compose about quarter of the population, how will it influence America’s national psychology in the future?

An intriguing new study in the journal Evolutionary Psychological Science appears to hold the answer. [Sex-Specific Developmental Effects of Father Absence on Casual Sexual Behavior and Life History Strategy, by Jessica Hehman & Catherine Salmon, Evolutionary Psychological Science, 2019] The study, conducted by two female researchers at Redlands University in California, explores the effect that father absence has on male and female children and also looks at how the magnitude of this impact differs in relation to the age the child is when frequent father absence commences.

Its central finding is extremely concerning: Father absence seems to cause children to adopt a so-called “Fast Life History Strategy” in which, in essence, they “live for the now.”

This is an adaptive response to an unstable ecology, argue the authors, because when your situation is unstable you could be wiped out at any moment and there may well be no pay-off for investment in others. Consequently, fast Life History (LH) strategists tend to be aggressive, uncooperative, sexually promiscuous and uncommitted. This, implies the study, is what US marital patterns are helping to create: the trauma and feeling of insecurity created by marital breakdown and father absence leads to a snowball effect of increasingly short-term oriented and selfish people.

The researchers, who questioned 392 people aged between 17 and 62 about their family background and sexual history, also unearthed some important differences based on sex and the age at which the individual’s family broke down.

Males had a faster LH strategy than females, though this was unsurprising as males have less to lose from the sexual encounter than females—they cannot get pregnant—and so they tend to be more sexually promiscuous. Also, for both males and females, the more time in childhood they had spent with their biological father, the fewer sexual partners they tended to have had as adults and the slower their LH tended to be. Slow LH people are cooperative, altruistic, caring parents and committed partners.

However, some important sex differences emerged when it came to the age the child was when the family collapsed. When Father Absence (FA) began in middle childhood (7-11), then females became fast LH strategists to a much more pronounced degree than males. But when FA began in adolescence (11-16), it was the male Life History Strategy which was more likely to be pushed in a faster direction.

That would mean the males are more environmentally sensitive at a later age or possibly that there is a specific time during puberty where sensitivity is very high. Puberty arrives later among boys than girls.

The impact of Life History Strategy was the same for both sexes if Father Absence began to early childhood.

Using various modeling, the authors managed to confirm that it really was the absence of the biological father that was associated with these effects, rather than the presence of a stepfather.

This, they observed, was crucial because step-fathers are single biggest committers of physical and sexual abuse against children. Their presence effectively creates the kind of unstable environment that would push a child towards a fast Life History Strategy.

They also noted that other studies have similarly found that it is specifically biological father absence rather than stepfather presence which correlates with risky sexual behavior later on. In other words, if you want to be a well-adapted adult then the presence of the biological father, especially during key phases of development, really does matter.

The key criticism, note Hehman and Salmon, is that there is a degree which a person’s Life History Strategy is a function of genetics. Indeed, the key measure that Hehman and Salmon employed—sexual behavior—has been estimated to be about 34% genetic. [Genetic Influences on Adolescent Sexual Behavior: Why Genes Matter for Environmentally-Oriented Researchers, by K. Paige Harden, Psychological Bulletin, 2014]

So could it simply be that the kinds of fathers who abandon their families, or the kinds of parents who split up rather than work through their difficulties, are congenital fast Life History Strategists who just pass these tendencies on to their offspring through heredity?

But although genetics is likely a factor, the authors note that similar sexual behavior patterns are found among children raised in stable, slow LH households when those children are subject to some acute stressor such as a parent suffering from depression. This, they aver, implies that father absence is likely to be causal in creating a fast Life History Strategy.

So what does this mean for the USA—or for the Republic of Ireland?

It means that easy divorce, the social acceptability of divorce, and welfare provision—meaning that single motherhood can be a lifestyle—are helping to create a society in which more and more people are more and more short-term-oriented in their attitude to life, as well as less and less cooperative and altruistic.

And not at at all “kinder and gentler,” in the words of George H.W. Bush’s notorious 1988 Republican National Convention acceptance speech.

Lance Welton [Email him] is the pen name of a freelance journalist living in New York.