![holder-ferguson_0[1]]()

When Eric Holder was in Ferguson in August, he said "I am the attorney general of the United States. But I am also a black man."

As it stands today, Republicans will add seats in the House and recapture the Senate on Tuesday.

However, the near-certainty is that those elections will be swiftly eclipsed by issues of war, peace, immigration and race, all of which will be moved front and center this November.

Consider. If repeated leaks from investigators to reporters covering the Ferguson story are true, there may be no indictment of officer Darren Wilson, the cop who shot Michael Brown.

Should that happen, militant voices are already threatening, "All hell will break loose." Police in the city and 90-some municipalities in St. Louis County, as well as the state police, are preparing for major violence.

After flying out to Ferguson to declare, "I am the attorney general of the United States. But I am also a black man." Eric Holder has once again brought his healing touch to the bleeding wound.

Yesterday, Holder said it is "pretty clear" that there is a "need for wholesale change" in the Ferguson police department.

But, Holder notwithstanding, that is not at all "clear."

Should the grand jury decide that Wilson fired in self-defense in a struggle with Brown over his gun, and fired again when the 6'4" 300-pound teenager charged him, what would justify a purge of the Ferguson police department or the dismissal of Chief Thomas Jackson?

What exactly have the Ferguson cops done to deserve the remorseless vilification they have received?

Yet, as St. Louis is bitterly divided over this incident and how it has been exploited, so, too, will be the nation, should November 2014 provide a replay of the urban riots of yesteryear.

And the president himself will invite a social explosion if he proceeds with White House plans for an executive amnesty for millions of illegal aliens residing in the United States.

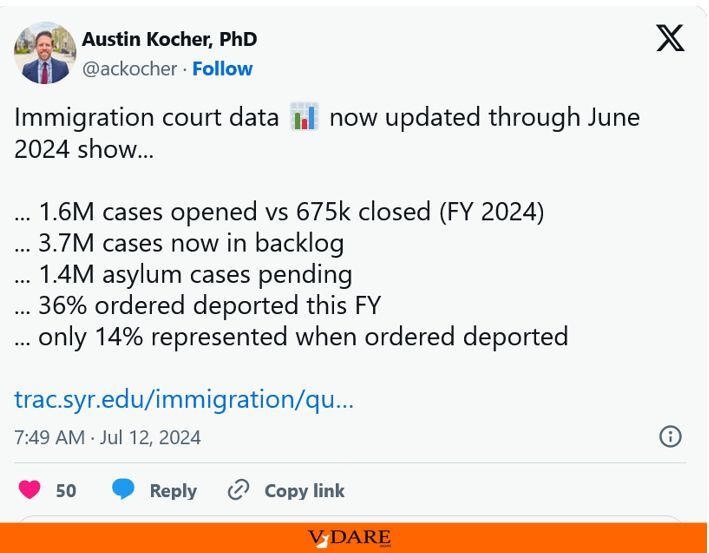

Obama is reportedly considering an end to the deportation of an entire class of illegals, perhaps numbering five million, providing them with work permits, and putting them on a path to permanent residency.

Such a post-election amnesty would bring a full-throated roar of approval from La Raza and the liberal wing of Obama's party, but it would evoke an even louder roar of protest from Middle America. And such a presidential usurpation of power would poison Obama's relations with the new Congress before it was even sworn in.

Undeniably, this would be a decision for which Obama would be remembered by history. But it is not at all clear that he would be well-remembered by his countrymen.

Indeed, among the reasons Obama did not act before the election was that he knew full well that any sweeping amnesty for illegals would sink all of his embattled red-state senators.

The corporate wing of the GOP might welcome the removal of the immigration issue from the national debate. But conservatives and populists will bring it back in the presidential primaries in the new year.

There are also two simmering issues of foreign policy likely to come to a boil and split Congress and country before Christmas.

First is America's deepening involvement in the war against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, for which Obama has never received Congressional authorization. When Congress returns for its lame-duck session, opponents of this latest Mideast war will be demanding that a new war resolution be debated and voted upon.

As yet, the president has made no convincing case that ISIS terrorists are primarily America's problem. Nor do we have a convincing strategy or adequate allied ground forces to fulfill Obama's declared mission to "degrade and destroy" the Islamic State.

What could bring this to the fore rapidly would be an Islamic State attack on Baghdad, the Green Zone, the U.S. embassy, or the Baghdad airport.

Some political and military analysts believe the attack on Kobane on the Syrian-Turkish border is a diversion from a planned attack on Baghdad to shock the Americans, just as the Tet Offensive of 1968 shocked an earlier generation.

While a military disaster for the Viet Cong, Tet convinced many Americans, Walter Cronkite among them, that the war could not be won.

Any such attack on Baghdad would likely trigger a debate inside the United States about whether, and at what price, we should try to put the Iraqi nation back together again.

Lastly, Nov. 24 is the deadline for the negotiations on Iran's nuclear program. If Obama decides that an agreement is acceptable to him and our European allies, and moves by executive action to lift some sanctions on Iran, he could face a rebellion in this city and on Capitol Hill.

Yet, should no agreement be reached, and the talks with Iran break off, there will be mounted a major drive by the War Party for the United States to exercise the military option to resolve the issue.

New battles at home, new wars abroad—this remains, unfortunately, the future prospect as well as the old reality.

![holder-ferguson_0[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/holder-ferguson_01.jpg)