Sunday’s Los Angeles Times has an upbeat front-page article about a Guatemalan town that has been transformed for the better by illegal immigration. The residents love America for its jobs and free stuff, shown by a “proliferation of U.S. flags” and new houses built in a style called “remittance architecture.”

Indeed, the money sent back as remittances is a lifeline to the poor country: Guatemalans abroad, mostly in the US, sent $9.5 billion home last year — 12 percent of the country’s GDP.

The local priest is quoted as supporting illegal immigration because “it serves a fundamental human need to survive.”

That’s right — stealing jobs from poor American citizens and generally driving down wages in the whole low-skilled sector in the US is sanctioned by the Catholic church which calls such Marxist views “Liberation theology”, and the church supports such lawbreaking because it benefits their own people.

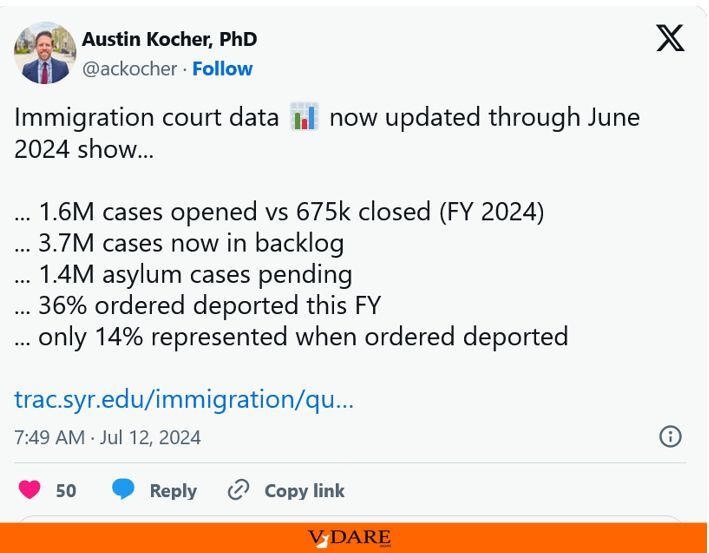

Of course, the article has no mention of the harm caused by the influx of millions of Third Worlders into the United States. The economy is booming, but wages are not rising because of the millions of foreign workers who compete against citizens by working cheap.

Plus, the Guatemalans now work as “menial laborers” but when automation becomes more widespread in a few years, they will not be cheap enough as the smart machines become even less expensive. At that point, their advantage as cheap illegal labor will evaporate and they will become jobless.

The foreigner invasion is also harmful to American students because schools are forced to reallocate their budgets to serve often illiterate, non-English-speaking foreigners.

As an example of the Guatemalan effect, the New York Times reported earlier this month:

Last year, the Palm Beach County school district enrolled 4,555 Guatemalan students in kindergarten through 12th grade, nearly 50% more than two years earlier. Many of the students come from the country’s remote highlands and speak neither Spanish nor English. The number of elementary school students in kindergarten through fifth grade more than doubled to 2,119 in that same period.

But the Los Angeles Times thinks that we Americans should celebrate the Third World invasion because it is a big benefit to Guatemala. The United States as the World Welfare Office is not questioned, nor is homemade reform abroad even considered.

To folks in this Guatemalan town, success stories start with a trek to the U.S., Los Angeles Times, July 21, 2019

This mist-shrouded mountain town in northwest Guatemala exudes a bustling air of good fortune, even prosperity, that may seem at odds with the landscape of subsistence cornfields and vegetable plots.

Concrete and stucco houses of three and even four stories tower over traditional dwellings crafted from adobe bricks and wooden planks.

The source of the housing boom isn’t income from crop sales or occasional tourism. Rather, Todos Santos runs on savings sent home from the United States.

“The United States helped me more than the Guatemala government ever did,” said Efrain Carrillo, 40, outside the three-story house he built with three years of savings from working in the north as a laborer a decade ago. “I was deported, but I am grateful to the United States.”

The house features a ground-floor grocery store to provide income, while Carrillo and his wife live upstairs and their two teenage children live with relatives in the United States.

Fluttering from a balcony is the Guatemalan flag, and next to it another common sight here: the Stars and Stripes.

The proliferation of U.S. flags is a testament to the importance of illegal migration here — and the difficulty of curtailing it.

For the moment, Mexican authorities, under pressure from the Trump administration, are cracking down on U.S.-bound migration from Central America, deploying Mexican National Guard troops along roads leading from the country’s southern frontier and stepping up deportations.

The effort appears to be yielding results, with apprehensions in June along the U.S. Southwest border down 28% compared with May.

But in the long term, such campaigns may do little to stop the exodus from places like Todos Santos.

Gang violence and political persecution — two of the most common reasons that Central Americans give when they claim asylum at the U.S. border — are not major problems here. The migration is driven by economics.

It has become deeply ingrained in the culture and a rite of passage for many young men and increasingly for women and children. Seemingly every family here has a close relative in el norte, from California to Florida, Oregon to Virginia.

“What would we do without the United States?” asked Julian Jeronimo, a 49-year-old teacher who spent four years in the San Francisco Bay area — working in restaurants and a fertilizer supply store while sharing an apartment with a half-dozen other migrants — before returning in 2004 to build a home. “We understand that the United States wants to control immigration. Of course, Trump is worried about criminals coming into the country, about terrorists. But people from Todos Santos go north to work.”

Estranged from Guatemala’s central government, the town seems closer emotionally to Oakland — a popular destination — than to Guatemala City. There is deep respect, even reverence, for the United States.

In recent years, Jeronimo has watched as parents have systematically taken their children north, diminishing enrollment in his rural school.

“This year we lost six children who left for the United States,” he said, adding that others plan to leave once they complete elementary school.

“They see that their brother has a new house or new car and they say, ‘I want that too.’ That is a very difficult mentality to change.”

In the United States, migrants from Todos Santos have traditionally been menial laborers — toiling in agriculture, landscaping, restaurants, and in meat- and poultry-processing plants.

But back home, they are something else: Pillars of the community, success stories to be emulated, trend-setters who finance lavish homes, sometimes with gated entrances, driveways and even lawns, mimicking suburbia USA in a grandiose style known as remittance architecture.

“There’s not a lot for people to do in Todos Santos to make a living,” said Jennifer L. Burrell, an anthropologist at the State University of New York in Albany who has studied the town for more than two decades. “So if you have aspirations, if you want to send your children to school, to educate them, to buy land and so forth — the only way you can accomplish that is by migration.”

The sprawling municipality of 33,000 people, nestled in the cool embrace of the Cuchumatanes mountain range, 8,000 feet above sea level, qualifies as a “transnational village,” Burrell says.

Residents marvel at the U.S.-reared sons and daughters of expatriates who return for visits.

“They are all grown up and they tell us they are still going to school, to the university!” said Fortunato Pablo Mendoza, a 67-year-old retired teacher. “Imagine that! Here there was nothing to do after finishing primary school but working in the fields.”

In Todos Santos, even tombs in the cemetery bear U.S. flags.

: :

Many Guatemalan migrants hail from rural outposts like Todos Santos, where most residents are of indigenous heritage and speak Mam, a Mayan tongue, while still donning traditional dress — embroidered skirts and blouses for women, striped pants and shirts and straw sombreros for men.

Officially, nearly 90% of Todos Santos residents live in poverty, but those statistics don’t take into full account the substantial income from remittances. Last year, Guatemalans abroad, mostly in the United States, sent home $9.5 billion, or 12% of the country’s gross domestic product.

People here expressed contempt for the Guatemalan government, which is notoriously corrupt and, according to the World Bank, spends less on health, education and other social services than most other Latin American countries.

Migration is the social safety net: Older migrants return as younger ones head north.

[. . .]

Father Edgar Tarax, who presided over the Mass, later expressed skepticism that Mexico’s current enforcement efforts — which have prompted some residents to put emigration plans on hold — could slow the movement north in the long term.

“How can emigration be stopped when it serves a fundamental human need to survive?” the priest asked in the church courtyard as worshipers nodded in approval. “Our people go north and work day and night, to send money back to build homes, to buy land, to help their families. That is the life of Todos Santos.”