Wednesday’s Washington Post gave front-page coverage to its sob story of poor coffee farmers in Guatemala who claim to be driven from their land by low prices for their crop.

Wednesday’s Washington Post gave front-page coverage to its sob story of poor coffee farmers in Guatemala who claim to be driven from their land by low prices for their crop.

The article says the “price of coffee has crashed” although the beverage is the important personal fuel of many millions in the First World. The press reports every few years that climate change may cause the extinction of the blessed coffee plant eventually, which you would think would raise its value, but that’s not what is happening now.

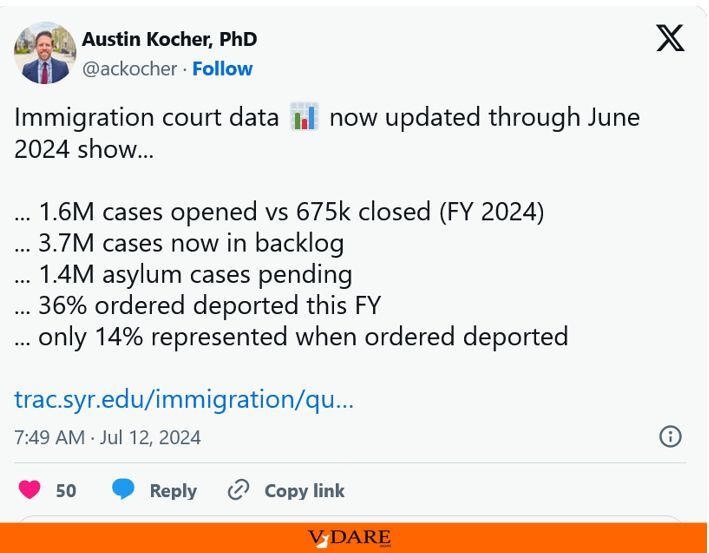

Of course, the upshot is that still more illegal aliens — a “staggering number” according to the Post — are now headed north to break into the US, but they have an excuse that the Post finds acceptable regarding the illegality of their entrance.

The Anchorage Daily News, linked below, reprinted the Post story:

Falling coffee prices drive Guatemalan migration to the United States, Washington Post, June 12, 2019

HOJA BLANCA, Guatemala – From his wooden hut in the foothills of the Sierra Madre, Rodrigo Carrillo can see the product of his life savings: A vast green sea of coffee plants, sprouting red berries like tiny Christmas ornaments.

Those plants once seemed a life-changing investment. Carrillo joined a cooperative that sells beans to Starbucks and several certified fair-trade organizations. In Guatemala’s fertile highlands, there was no faster way out of poverty than to supply American coffee drinkers.

But in recent years, the price of coffee has crashed, leaving Carrillo, 48, with a choice to make.

Last month, he pulled out a wrinkled map of the U.S.-Mexico border and pointed to the spot on the edge of Arizona where he plans to cross with his 5-year-old son.

“I’m leaving in 11 days,” he said. “There’s no money in coffee anymore.”

Guatemala is now the single largest source of migrants attempting to enter the United States – more than 211,000 were apprehended at the Southwest border in the eight months from October to May. Here in western Guatemala, one of the biggest factors in that surge is the falling price of coffee, from $2.20 per pound in 2015 to a low this year of 86 cents – about a 60% drop. Since 2017, most farmers have been operating at a loss, even as many sell their beans to some of the world’s best-known specialty-coffee brands.

A staggering number of those farmers have decided to migrate.

President Donald Trump has blamed weak border security in Mexico and loopholes in America’s asylum system for the increase. The deal by Mexico and the United States last week focused largely on deterring Guatemalan migrants through tougher enforcement. But many here are still considering the journey – and falling incomes are a major part of the calculus.

More than half of Hoja Blanca’s 100-person coffee cooperative have either migrated or have children who have migrated in the past two years. Abandoned coffee farms lie fallow along the dirt roads that wind through the region.

“What we’ve seen is that the migration problem is a coffee problem,” said Genier Hernández, the head of Hoja Blanca’s coffee cooperative.

He’s not alone in making that connection. In working to combat migration, the U.S. Agency for International Development has funded programs to assist coffee producers. Trump has threatened cuts to those efforts.

When acting homeland security secretary Kevin McAleenan traveled to Guatemala in May, he invited coffee growers, including Hernández, to meet with him. The growers showed him a PowerPoint presentation, titled “Coffee and Migration,” with graphs illustrating how much farmers were losing.

“I asked him what he could do about the price,” Hernández said. (Continues)