From The New Yorker:

UNTANGLING THE IMMIGRATION DEBATEIt’s kind of like how I’m an Apple shareholder, I just haven’t gone through the formality of buying any Apple shares yet, so if somebody in the Apple treasury department wanted to sell me some shares of Apple stock for half price, that would be cool since it would be in the interest of Apple shareholders, or at least one future Apple shareholder, me, at least after I buy the shares for half their value.What do we owe people in other countries who would like to come to this one?

By Kelefa Sanneh

BOOKS OCTOBER 31, 2016 ISSUE

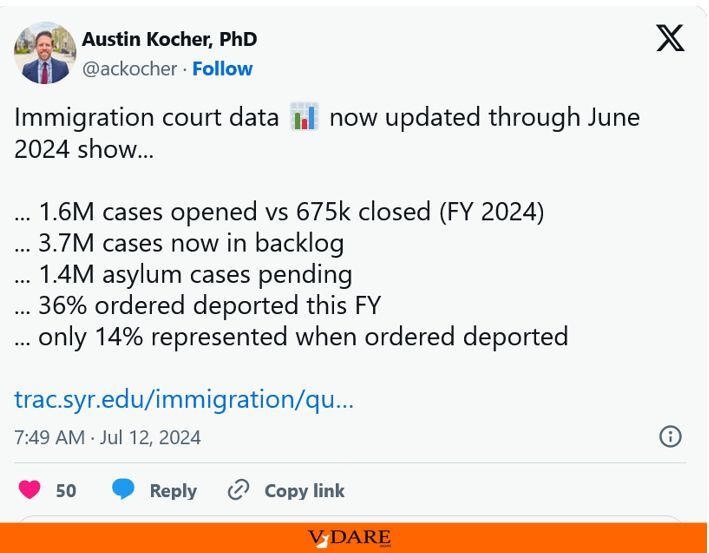

… In this country, the rise of Donald Trump may mark the demise of the bipartisan immigration consensus; this year, an Open Borders Amendment seems even more far-fetched than it did in 1984. How much immigration should the government allow? One answer that open-borders supporters might offer is practical, if unsatisfying: as much as it can get away with.

Meanwhile, it is not just Trump who promises to put America first. Politicians of all stripes assure us that their favored policies will make Americans stronger together—insisting that it is possible, after all, to be wromantic and right. But Carens makes a startling assertion toward the end of his book. “Admission of refugees,” he writes, “does not really serve the interests of rich democratic states.” In saying so, he seeks not to stem the tide but to make it clear that morality requires states to act in ways that may not be to their advantage. The good news is that voters, too, tend to be driven by much besides self-interest—if this were not the case, we might already have embraced the high-skilled-immigrant program that Borjas says would enrich us. Voters seem to like the idea of providing sanctuary to refugees, especially if they can be convinced that the refugees aren’t gaming the system. In America, especially, voters respond to the sentimental but not fictitious notion that their country draws immigrants from around the world, all hoping and expecting to do better than they could have done at home. Immigration may be, as Borjas puts it, “a net economic wash,” and yet there are still good and strong reasons for us to say that we want more of it. There is, after all, one class of Americans who stand to gain enormously from immigration. The only catch is that these Americans are not Americans at all—not yet. ♦

That’s basically the same faulty argument that I offered to my finance professor 35 years ago in MBA school and got shot down. As I wrote in VDARE in 2005:

By “citizenism,” I mean that I believe Americans should be biased in favor of the welfare of our current fellow citizens over that of the six billion foreigners.Let me describe citizenism using a business analogy. When I was getting an MBA many years ago, I was the favorite of an acerbic old Corporate Finance professor because I could be counted on to blurt out in class all the stupid misconceptions to which students are prone.

One day he asked: “If you were running a publicly traded company, would it be acceptable for you to create new stock and sell it for less than it was worth?”

“Sure,” I confidently announced. “Our duty is to maximize our stockholders’ wealth, and while selling the stock for less than its worth would harm our current shareholders, it would benefit our new shareholders who buy the underpriced stock, so it all comes out in the wash. Right?”

“Wrong!” He thundered. “Your obligation is to your current stockholders, not to somebody who might buy the stock in the future.”

That same logic applies to the valuable right of being an American citizen and living in America.

Just as the managers of a public company have a fiduciary duty to the current stockholders not to diminish the value of their shares by selling new ones too cheaply to outsiders, our leaders have a duty to the current citizens and their descendants.