An interesting question is the historical development of the current inner city black tradition of spray-and-pray shooting at social events in the general direction of the intended victim that also wounds so many besides the intended. This tendency in black on black shootings became such a recurrent feature of crime news during the racial reckoning that it led me to coin “Sailer’s Law of Mass Shootings:”

If at least four people besides the gunman were shot and more were killed than wounded, the shooter was likely nonblack.

If more people were wounded than killed, the shooter (or shooters) is likely black.

For example, in 2020, murders were up about 40% in NYC, but the total number of people struck by bullets was up by over 100%.

There might be a database out there somewhere that would shine light on the question of when did the number of wounded to the number of dead start going up so much. To disentangle it from better medical care, you’d have to compared the dead to wounded ratios for blacks versus nonblacks.

But in the current absence of data, I figured I’d start with culture.

When in St. Joseph, Missouri on a lecture tour of the United States, Oscar Wilde was taken to see the house in which Robert Ford had, only days before, shot Jesse James. People were dismantling the house to have souvenirs of this already legendary event. Oscar observed, “The Americans are certainly hero-worshipers, and always take their heroes from the criminal classes.”

Americans consumed a lot of Penny Dreadful works during the 19th Century about gunmen in the Wild West. But the most admired gunmen were those who fought fair fight duels in streets emptied of bystanders.Wounding, say, the schoolmarm during a shootout would likely get you lynched by the unanimous decision of the men of the mining town. There was much emphasis in the lore on shooting accuracy, unlike today when quantity of shots fired seems more prestigious than quality of aim.

African-Americans maintained this tradition of hero-worshipping the criminal classes at least up through the gangsta rap era, and it can be traced in the blues through songs such as “Stagger Lee.”

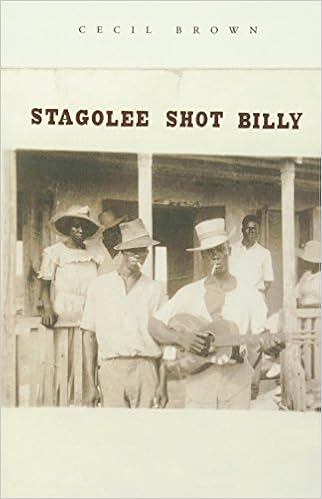

On Christmas 1895, there was a legendary black-on-black shooting in St. Louis in which Stagger Lee, a prominent pimp, shot his friend Billy that has provided so much fodder for musicians ever since:

It’s not obvious why this rather mundane event became so famous, with Stagger Lee becoming legendary as a symbol of the black Bad Man but it really did happen. St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1895 reported:

It’s not obvious why this rather mundane event became so famous, with Stagger Lee becoming legendary as a symbol of the black Bad Man but it really did happen. St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1895 reported:

William Lyons, 25, a levee hand, was shot in the abdomen yesterday evening at 10 o’clock in the saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan Streets, by Lee Sheldon [sic], a carriage driver. Lyons and Sheldon were friends and were talking together. Both parties, it seems, had been drinking and were feeling in exuberant spirits.

There’s that word again: exuberance.

The discussion drifted to politics, and an argument was started, the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon’s hat from his head. The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon withdrew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen. When his victim fell to the floor Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away. He was subsequently arrested and locked up at the Chestnut Street Station. Lyons was taken to the Dispensary, where his wounds were pronounced serious. Lee Sheldon is also known as ‘Stag’ Lee.

Although Billy died of his wound, Stagger Lee was sentenced to 25 years rather than death. But he was paroled 14 years after the murder (did they have Soros DAs in 1914?). But Stagger Lee was soon back in prison for robbery, where he shortly died of TB.

Wikipedia writes:

Stagger Lee has become an archetype with some Black People who admire the gangster type; a parallel to the glorification of the outlaw by a section of mainstream society. In this variation, he is the embodiment of a tough black man; one who is sly, streetwise, cool, lawless, amoral, potentially violent, and who defies white authority.

But, in the original news account, it is implied that Stagger Lee fired, perhaps only once, and hit the man he aimed at. Apparently, back in 1895, Stagger Lee didn’t accidentally wing a few guys playing whist in the background and the man delivering ice like so many modern bad dudes would have.

In Lloyd Price’s hit rock ‘n’ roll version above, there is, however, some collateral damage added to the tradition:

Stagger Lee shot Billy

Oh, he shot that poor boy so bad

‘Till the bullet came through Billy and it broke the bartender’s glass

But the mid-20th Century lyric praises Stagger Lee not for shooting wildly but for shooting accurately and so powerfully that the bullet went through Billy and broke the bartender’s glass.

So maybe there was a development over the course of the 20th Century in which the amount of collateral damage a Bad Man was willing to impose on innocent bystanders via his bad shooting came to be recognized as impressive evidence of his Badness?

Digital humanities researchers might be interested in pursuing this question through analyzing song lyrics. Somebody who likes rap music might look for when the idea that a truly, admirably Bad Man will open fire into a crowd rather than wait to get a clear shot at his intended victim.