Bottom line: it's racial. I've made this point myself, e.g. in my 2001 China Diary:

"Did they ask to see your passport?" I wanted to know. No, she said, they had not. Nor did anyone else at any future point. This shows that the criterion is blood, not nationality. To put it more plainly, the whole thing is frank racial discrimination. [China Diary by John Derbyshire; National Review Online, July-August 2001.](You can argue that it's really ethnic, not racial. After 4,000 years of absorbing border tribes and enduring long partial or total conquest and occupation by Turks, Tibetans, Mongols, Manchus, Iranians, etc., any match between the self-identifying Han population of China and the concept of biological race is problematic. I'll leave that for another time.)

Over to The Economist.

Five men who ran a bookshop in Hong Kong disappeared in mysterious circumstances in late 2015. One was apparently spirited away from the territory by agents from the mainland; another was abducted from Thailand. All later turned up in Chinese jails, accused of selling salacious works about the country’s leaders. One bookseller had a British passport and another a Swedish one but the two suffered the same disregard for legal process as Chinese citizens who anger the regime. Their embassies were denied access for weeks. The government considered both these men as intrinsically “Chinese”. This is indicative of a far broader attitude. China lays claim not just to booksellers in Hong Kong but, to a degree, an entire diaspora.There is an amusing passage in Chapter 13 of Peter Brimelow's 1995 book Alien Nation where Peter phones the Washington, D.C. embassies of those nations that send large numbers of immigrants to the U.S.A. to ask about rules for immigrating into those countries.China’s foreign minister declared that Lee Bo, the British passport-holder, was “first and foremost a Chinese citizen”. [The upper Han: The world’s rising superpower has a particular vision of ethnicity and nationhood that has implications at home and abroad; The Economist, November 19th 2016 (but I think you need a subscription to read it online).]

Chinese Embassy Official [laughs]: "China does not accept any immigrants. We have a large enough population …"Things haven't changed much in 21 years. The Economist:

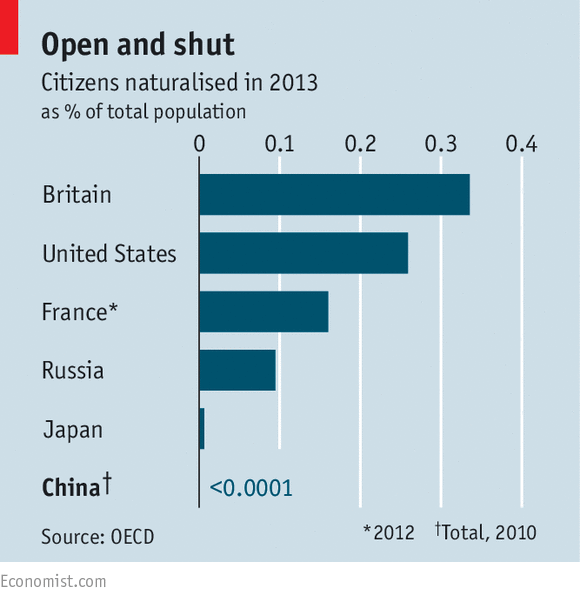

China today is extraordinarily homogenous. It sustains that by remaining almost entirely closed to new entrants except by birth. Unless someone is the child of a Chinese national, no matter how long they live there, how much money they make or tax they pay, it is virtually impossible to become a citizen. Someone who marries a Chinese person can theoretically gain citizenship; in practice few do. As a result, the most populous nation on Earth has only 1,448 naturalised Chinese in total, according to the 2010 census. Even Japan, better known for hostility to immigration, naturalises around 10,000 new citizens each year; in America the figure is some 700,000 (see chart).

It's the same with refugees.

China’s Han-centred worldview extends to refugees. In a series of conflicts since 2009 between ethnic militias and government forces in Myanmar the Chinese government has consistently done more to help the thousands escaping into China from Kokang in Myanmar, where 90% of the population is Han, than it has to aid those leaving Kachin, who are not Han. Non-Chinese seem just as beguiled by the purity of Han China as the government in Beijing. Governments and NGOs never suggest that China take refugees from trouble spots elsewhere in the world. The only large influx China has accepted since 1949 were also Han: some 300,000 Vietnamese fled across the border in 1978-79, fearing persecution for being “Chinese”. China has almost completely closed its doors to any others. Aside from the group from Vietnam, China has only 583 refugees on its books. The country has more billionaires. [My italics.]Pause a moment to reflect on those numbers: 1,448 naturalized citizens, 583 refugees, in a population of 1.4 billion.

Then pause a moment longer to reflect on the hypocrisy implicit in those sentences I italicized.

The open-borders Economist of course clicks its editorial tongue in disapproval of all this ethnocentrism.

A closed China wilfully narrows its access to the global pool of professional talent. The government grants surprisingly few work visas. Foreigners made up 0.05% of the population in 2010, according to the World Bank, compared with 13% in America . . .Now, I'd be the last person to offer Communist China as a model nation-state. I detest the ChiComs' brutish gangster-despotism, as 30-plus years of my opinionating amply show.At the same time its own citizens are heading overseas. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese leave every year to study or work abroad. Many have returned to China to work and are a driving force of innovation and high-tech development. Far more do not come back: of the 4m Chinese who have left to study abroad since 1978, half have not returned, according to the Ministry of Education. Yet because China bans dual nationality those who become eligible for a foreign passport, by birth, wealth or residency, face a choice. The result is that the brain-drain is mostly one-way. Thousands of Chinese renounce their citizenship every year, but because it is so difficult for foreigners to become Chinese, no counterbalancing group opts in.

China’s Han-centred worldview is not just a historical curiosity. It is a decisive force in the way it wields its growing power in the world—a state that respects neither equality nor civil liberties at home and may ignore them abroad too. In economic terms, China will cut itself off from an important source of economic growth, waste resources in discriminating against ethnic minorities and fail to use its human talent to better effect. Exacerbating ethnic tensions may spur the separatism it fears. And by sorting citizens abroad by their ethnic identity rather than their national one—whether by claiming to defend “its own” or punish them for disloyalty—China risks clashing with other countries. Over the past century, China’s founding myth has been a source of strength. But as it looks forwards, China risks being borne back ceaselessly into its own past.

And I don't think the awfulness of the ChiCom government tells us anything about nationalism. As I have argued before on this site:

Mid-20th-century despotic nationalism was bad not because nationalism is bad, but because despotism is bad. [Derb's June Diary; VDARE.com, July 2nd 2016.]The determination of the ChiComs to keep their country Chinese does, though, remind us that the current conflict between nationalism and globalism is not just an intellectual debate among politicians in the Free World; it is an issue of major world-historical importance that will likely shape life on our planet for the rest of this century.

Footnote: When I discussed this article with my ethnically-Chinese wife, she chuckled at the last sentence here:

Many Chinese today share the idea that a Chinese person is instantly recognisable—and that an ethnic Han must, in essence, be one of them. A young child in Beijing will openly point at someone with white or black skin and declare them a foreigner (or “person from outside country”, to translate literally). Foreign-born Han living in China are routinely told that their Mandarin should be better (in contrast to non-Han, who are praised even if they only mangle an occasional pleasantry).She: "Yes: Nobody's harder on the Chinese than we Chinese ourselves."