Earlier: The Continuing Crisis: Too Few Plaques For Blacks and British Oscars Announce News Steps To Increase Plaques For Blacks

When you walk around the nice parts of London, you quickly come across oval blue plaques bearing the name of some historic personage who once lived at this spot. For example, the first I can remember from1980 is the plaque for the doomed South Pole explorer Robert Scott. There really have been a lot of famous Brits and many of them lived in London at one point or another.

Of course, these days, that’s a sore spot because almost all of these famous Brits are white. How can we tolerate this history? Such knowledge might undermine the self-esteem of blacks, which, as we all know, is incredibly fragile.

Of course, these days, that’s a sore spot because almost all of these famous Brits are white. How can we tolerate this history? Such knowledge might undermine the self-esteem of blacks, which, as we all know, is incredibly fragile.

From The Guardian:

Only 2% of blue plaques in London commemorate black people

Tobi Thomas, Aamna Mohdin and Pamela Duncan

Tue 5 Oct 2021 02.00 EDT

Blue plaques commemorating notable black figures still make up just 2.1% of the individuals honoured across London, according to a Guardian analysis.

More than 1,160 notable people are name-checked on the scheme’s 978 plaques. But of the those awarded plaques, 96% are white, while only 4% of figures have been from a black, Asian or minority ethnic background.

On Tuesday, a husband and wife who escaped from slavery in the US and came to Britain in the mid-19th century, where they campaigned for abolition and social reform, become the latest people to be commemorated by London’s distinctive historical markers.

William and Ellen Craft had been slaves in the southern state of Georgia before managing to escape, with the fair-skinned Ellen posing as a white man and William as “his” servant. After arriving in England as refugees in 1850, they toured the UK campaigning against slavery, before settling in Hammersmith.

Although the scheme was introduced in the 19th century, it was not until 1975 that the first blue plaque to commemorate a black person, the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor [not the author of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Samuel Taylor Coleridge] was introduced, and a further 11 years until the next was erected at the Leyton home of South African writer and political activist Sol Plaatje.

Whose heart doesn’t pound a little faster at the mention of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Sol Plaatje?

The majority of the commemorated black figures first achieved this status in the past two decades: 81% of the blue plaques dedicated to notable black figures were erected since 2002.

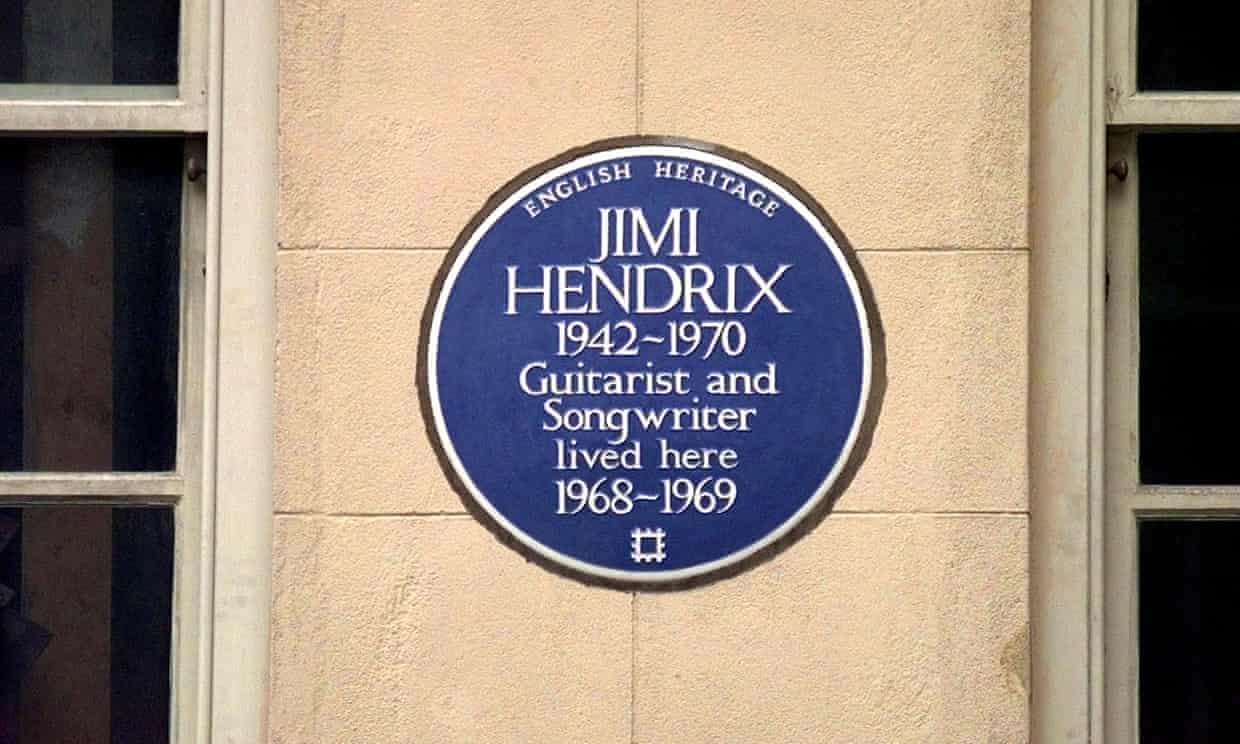

Disparities also exist within the categories by which black and non-black figures are recognised. Black nominees are overrepresented in the categories that primarily commemorate music and dance, which make up almost a third (30%) of all the plaques dedicated to black people, compared with just 8% of all honourees.

The singers Bob Marley and Elizabeth Welch are both commemorated, as is guitarist Jimi Hendrix.

Other black figures celebrated by the scheme including the footballer Laurie Cunningham, cricketer Sir Learie Constantine and the nurse Mary Seacole. John Archer, the first black person to hold a senior public office in London, is represented, as is racial equality campaigner and founder of the League of Coloured Peoples, Dr Harold Moody.

The only ones of these plaques that I can imagine international tourists finding interesting are Marley and Hendrix, neither of whom were Brits. It’s almost as if blacks haven’t played much of a role in London history.