From Scientific American:

Africa’s Population Will Soar Dangerously Unless Women Are More EmpoweredOne thing we need is more honest academic research into how African men and women think. Anthropologist Henry Harpending had a whole series of great stories about what his hosts told him during his years living with African tribes. But you’re not supposed to figure out the logic of sub-Saharan cultures the way Henry did. You’d have to listen to about a million hours of NPR shows set in Africa to figure out what’s really going on.Population projections for the continent are alarming. The solution: empower women

By Robert Engelman on February 1, 2016

By 2100 Africa’s population could be three billion to 6.1 billion, up sharply from 1.2 billion today, if birth rates remain stubbornly high. This unexpected rise will stress already fragile resources in Africa and around the world.

A significant fertility decline can be achieved only if women are empowered educationally, economically, socially and politically. They must also be given easy and affordable access to contraceptives. Following this integrated strategy, Mauritius has lowered its fertility rate from six to 1.5 children; Tunisia’s rate dropped from seven to two.

Men also have to relinquish sole control over the decision to have children and refrain from abusing wives or partners who seek birth control.

For such efforts to succeed ultimately, government leaders must encourage public and policy conversations about slower population growth.

Earth is a finite place. The more people who inhabit it, the more they must compete for its resources.

Although human population has grown steadily, developments in recent decades have been encouraging. Globally, women today give birth to an average of 2.5 children, half as many as in the early 1950s. …

Then there is Africa, where women give birth on average to 4.7 children and the population is rising nearly three times faster than in the rest of civilization. … By the end of this century, demographers now project, Africa’s inhabitants will triple or quadruple.

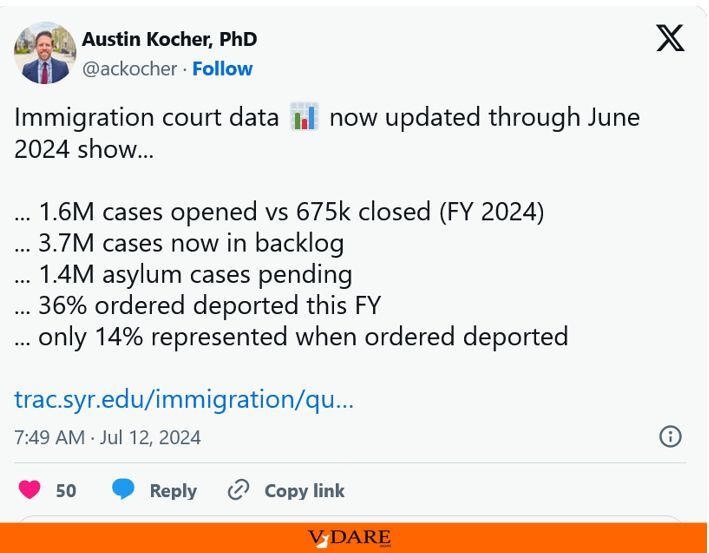

For years the prevailing projections put Africa’s population at around two billion in 2100. Those models assumed that fertility rates would fall fairly rapidly and consistently. Instead the rates have dropped slowly and only in fits and starts. The United Nations now forecasts three billion to 6.1 billion people—staggering numbers. Even conservative estimates, from places such as the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, now see Africa at 2.6 billion. The U.N. has in recent years continually raised its midline projection for 2100 world population, from 9.1 billion in a 2004 estimate to 11.2 billion today. Almost all of the unanticipated increase comes from Africa.

Extreme growth threatens Africa’s development and stability. Many of its inhabitants live in countries that are not especially well endowed with fertile soils, abundant water or smoothly functioning governments. Mounting competition for nourishment and jobs in such places could cause strife across the region and, in turn, put significant pressure on food, water and natural resources around the world, especially if Africans leave their nations in droves, which is already happening. As many as 37 percent of young adults in sub-Saharan Africa say they want to move to another country, mostly because of a lack of employment.

Africa needs a new approach to slowing its population rise, to preserve peace and security, improve economic development and protect environmental sustainability. And the world needs to support such efforts. From the 1960s to 1990s, international foundations and aid agencies urged African governments to “do something” about escalating population growth. That “something” usually amounted to investing in family-planning programs without integrating them with other health care services, plus making government statements that “smaller is better” for family size.

From the mid-1990s onward, however, silence descended. Calling population growth a problem was seen as culturally insensitive and politically controversial. International donors shifted their focus to promoting general health care reform—including fighting HIV/AIDS and other deadly diseases. …

The prospect of a crowded, confrontational and urban continent has begun to worry Africa’s national leaders, most of whom have traditionally favored population growth. They are starting to speak up. …

It is not surprising that access to family planning is one of the steps receiving renewed attention. Today only 29 percent of married African women of childbearing age use modern contraception. On all other continents the rate is solidly more than 50 percent. Surveys also show that more than a third of African pregnancies are unintended; in sub-Saharan Africa 58 percent of women aged 15 to 49 who are sexually active but do not want to become pregnant are not using modern contraception. Djenaba, a teenage girl whom I interviewed some years ago, testified to that tension in her remote village in Mali, a country where only one woman in 10 uses contraception. Just past her midteens, she was already the mother of two young children. When I first asked how many children she wanted to have, she responded, eyes downcast, “As many as I can.” But after half an hour of conversation she faced me directly, her eyes misting, and told me she wished she could take contraceptive pills to get some rest from childbearing and soon stop altogether. …

Niger in West Africa offers an example of why an integrated strategy for lowering population growth, combined with government involvement, is so critical. There, in one of the world’s poorest nations, the average fertility is 7.5 children per woman, and it has barely dipped since measurements began in 1950. Women and men surveyed say that the ideal family is even larger.

Demographers are a bit stumped as to why, but the high number probably stems from a combination of factors. They include religious beliefs, high death rates among young children, a large proportion of rural residents who depend on children to work poor land, large families being valued as a matter of status (especially for men), and women having low status (children prop up women’s value in marriages, which are often polygamous). Child-rearing is typically shared in extended families, notes demographer John Casterline of Ohio State University, easing the burden—and therefore easing the decision among parents to have another baby. Mamadou Tandja, president of Niger until 2010, used to spread his arms to denote the vast expanse of his country, bigger than Texas, telling visitors there was plenty of room for a much larger population. …

Whether Africa finishes the century with several billion people or something much closer to its current 1.2 billion could make all the difference in its development, prosperity and resilience in the face of inevitable challenges.

This article was originally published with the title “Six Billion in Africa”